By Marinella Davide*

The rules on the cooperative approaches, referred to in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, were one of the key agenda items to be agreed at COP26. Article 6 provisions represented, indeed, the last missing piece of the Paris rulebook, whose major components were approved at COP24 in Katowice (Poland).

In Glasgow, countries finally found an agreement on a thorny issue, whose rules have the potential to support the achievement of the Paris Agreement’s goals at a lower cost and provide larger incentives for private sector investments.

A technical and political issue

Cooperative approaches include voluntary mechanisms that, within the Paris Agreement, will allow countries to collaborate in pursuing higher ambition.

According to Article 6, cooperative approaches can take three forms:

- voluntary cooperation, including the use of internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs) as per Article 6.2

- a new mechanism to contribute to the mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions and support sustainable development, as per Article 6.4

- non-market mechanisms, as per Article 6.8

In other words, these three paragraphs open to the door for countries to bilaterally trade emission reductions, or other types of mitigation outcomes, to develop a new carbon crediting mechanism, often referred to as the “Sustainable Development Mechanism”, under the supervision of a UN body, for the trade of emissions reductions, and to cooperate in other forms that don’t involve trade.

Major points of discussion in Glasgow were related to how to preserve environmental integrity and avoid double-counting of transferred emission reductions, how to ensure that these mechanisms deliver increased ambition and progression, how much of the share of proceeds has to be dedicated to adaptation in developing countries, how to integrate a language on human rights protection and rights of local and indigenous people.

The new sustainable development mechanism will rise from the ashes of the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), created under the Kyoto Protocol

Effective rules on transparency, ambition and robust accounting would allow these mechanisms to unlock further mitigation potential and leverage private investments. On the contrary, poorly designed rules would offer loopholes, which could undermine the Paris Agreement’s fundamentals. Tough negotiations on technicalities went hand in hand with complex political discussion, with some countries more reluctant than others to the idea of limiting the way they can achieve emissions reductions.

What the negotiating texts say

In particular, the approved documents clarify the definition of “Internationally transferred mitigation outcomes” as real, verified and additional emission reductions and removals, including mitigation co-benefits resulting from adaptation actions or economic diversification plans. These emission reductions have to be generated after 2020 and measured according to IPCC methodologies and metrics, or metrics agreed among Parties in the case of non-GHG targets.

Each party to the Paris Agreement engaging in the transfer of mitigation outcomes shall apply corresponding adjustments, meaning that the same emission reduction cannot be claimed by more than one country as counting toward the achievement of their climate commitments, or by more than one entity in the case the country allows others to claim it for other purposes. The decision text offers different methodologies to follow according to the type of targets, along with rules on periodical reporting and review to ensure transparency, accuracy, and comparability of information.

A database and a centralized accounting and reporting platform will be created and managed by the UNFCCC secretariat to keep track and review information provided by countries.

The new sustainable development mechanism will rise from the ashes of the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), created under the Kyoto Protocol. The decisions on article 6.4, indeed, appoint a new Supervisory body that will review the features of the CDMs in order to apply the revised rules by the end of 2023. Moreover, CDM projects and activities will be allowed to transition into the new mechanism through 2025, as will the certified emission reduction units from CDM projects emitted from 2013 onwards. However, they can only be used towards the first NDC achievement and will be classified as pre-2021 emission reductions.

The agreement reached in Glasgow is undoubtedly not perfect, but it offers a package of detailed rules to govern cooperation among countries in a transparent and accountable manner

The name of the emission reduction units achieved under the new mechanism is A6.4ERs and they may be used towards NDCs achievement or for international mitigation purposes. Both public and private entities can participate in emission reductions activities, which should achieve emission reductions that would not take place otherwise. To ensure that the new mechanism contributes to the so-called “overall mitigation in global emissions” (OMGE), a minimum of 2% of the A6.4ERs will be cancelled out at their issuance.

In addition, another 5% of each of A6.4ER will be transferred to the Adaptation Fund to support particularly vulnerable developing countries in coping with the cost of adaptation.

In this case, as well, corresponding adjustments need to be applied when emission reductions are transferred, with the exception of the CDMs credits.

As for the non-market mechanisms, the guidelines identify some initial focus areas, such as adaptation, resilience and sustainability; mitigation measures that also contribute to sustainable development; and development of clean energy sources. Overall, there is a call to both the public and private sectors as well as to research and civil society to contribute by proposing, developing, and implementing non-market cooperative mechanisms, with an invite to parties and observers to submit examples and experiences. A Glasgow Committee on Non-Market Approaches is established, and it will meet twice a year up to 2027, to further advance the development of Article 6.8’s cooperative mechanisms.

In implementing actions under the three mechanisms, countries have to respect and promote human rights, the rights of indigenous peoples, local communities and of other people in vulnerable situations as well as ensure gender equality and intergenerational equity.

Beyond words

The guidelines on Article 6 mechanisms have been welcomed with mixed feelings, as some observers and stakeholders point to the positives whereas others focus on the potential weaknesses offered by the text.

The agreement reached in Glasgow is undoubtedly not perfect, but it offers a package of detailed rules to govern cooperation among countries in a transparent and accountable manner. Rules on partial cancellation and corresponding adjustments ensure that key elements to preserving climate integrity are now on paper, although with some weak spots.

Bottom line: Parties needed clear guidance on A6 at #COP26; they have it. Text is strong on no-double-counting.

The potential is there for A6 to drive greater ambition through cooperation.

Buyers must ensure integrity by refusing pre-2020 CERs. Civil society will be watching.

— Nat Keohane (@NatKeohane) November 13, 2021

The corresponding adjustments, in particular, represent a crucial component to avoid double counting of emission reductions towards both the achievement of NDCs and also for other mitigation purposes. Whereas for the former it is pretty clear that no more than one country can use the same emission reduction unit in its national account, some methodologies in article 6.2 and the language on the use of emission credits for other mitigation purposes in article 6.4 offer potential for double-counting of emissions used in the aviation sector carbon offsetting scheme (known as CORSIA) or in other voluntary carbon markets.

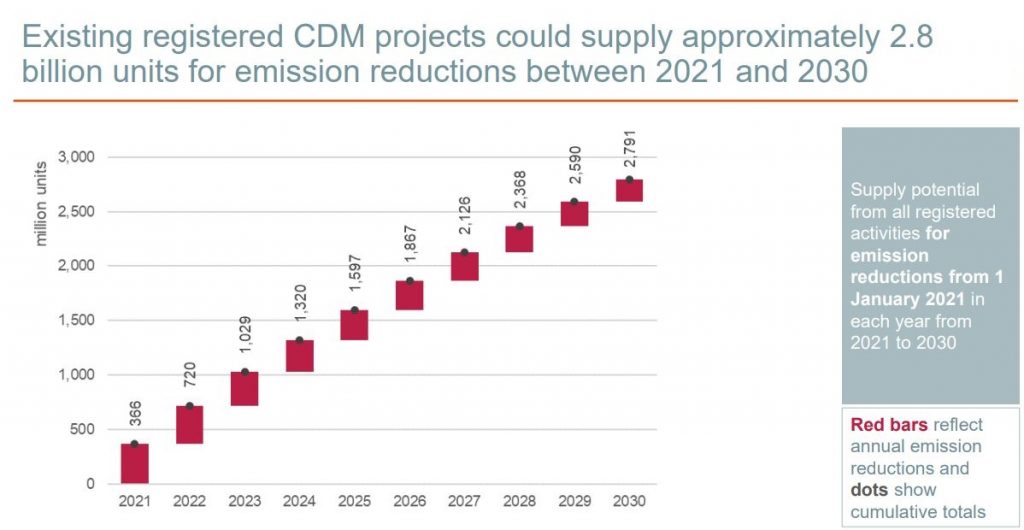

The carry-over of the Kyoto era’s projects and emission reductions also raised widespread concern. From a methodological and procedural point of view, reviewing and improving existing rules will save nearly two decades of work on validations, exchanges, and registries. However, in terms of climate ambition, they actually represent emission reductions that already took place and therefore are not additional. An analysis by the NewClimateInstitute widely circulated during negotiations estimates that up to 2.8 billion carbon credits could flow into the Paris Agreement from these projects. The possibility of using them only for the first NDC and the fact that such emissions reductions will be clearly labelled (and therefore easily identifiable) may somehow limit their usage.

Overall, how much governments and private companies will choose to exploit these potential loopholes, also considering the increasing request of carbon offsets, will be of crucial importance for the success of these mechanisms.

* Marinella Davide is a research affiliate at the Euro-Mediterranean Center on Climate Change. She is a postdoctoral research fellow at Ca’ Foscari University and at Harvard University. She is the recipient of a EU-funded Marie Sklodowska-Curie Global Fellowship. Her research focuses on the analysis of national and international policies on climate change and low-carbon energy and their linkages with sustainable development. She has experience in EU climate policy, EU ETS and UNFCCC negotiations