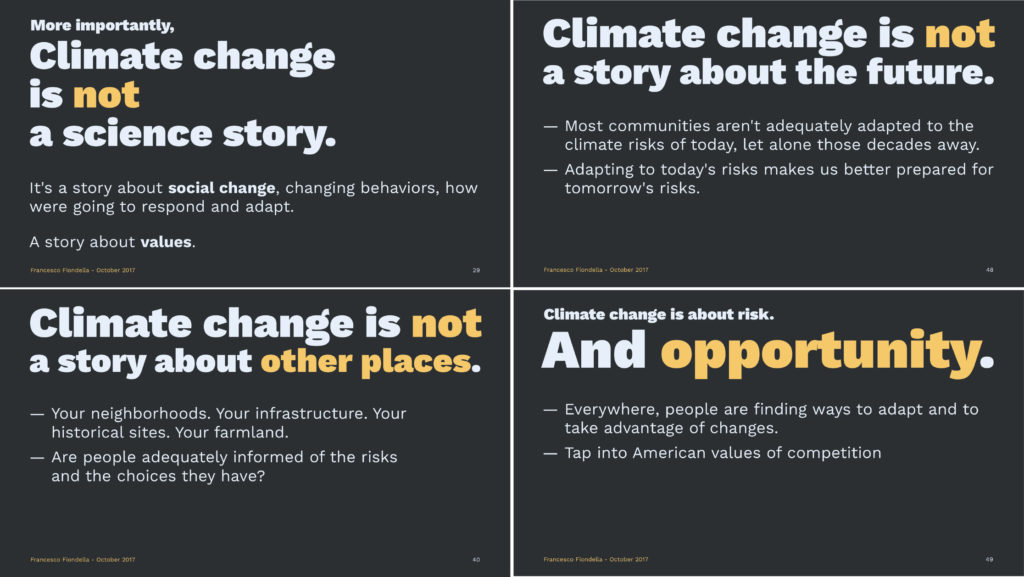

People, action, solutions, and opportunities. These four keywords can drive effective climate communication, because “climate change is not a story about the future”. A talk with Francesco Fiondella, Director of Communications of the International Research Institute for Climate and Society, Earth Institute, Columbia University.

In the last few years and months we have seen growing attention for climate change in mainstream media. We need the media to talk about the climate if we want to accelerate awareness and action: do you think there is progress or is it just a new fashion?

“I am from the US, and I definitely see more discussions about climate change. It’s seeping into a wider public consciousness. I also see the media being more nuanced in the way it covers climate change. Reporters are more sophisticated and careful in showing how it impacts every part of our lives: they are really thinking about how to tell the climate story beyond just the climate science context.

We can find a lot of evidence of very good storytelling and climate communication. I think the best places currently are The Guardian, and The New York Times, which is connecting climate to its coverage of business, tech, real estate. For example, stories about the fashion industry being directly linked to climate and sustainability concerns. And there are more partnerships now, among media and science.

Media is important, because the more climate coverage it gives, the more awareness it raises in society. And I think there is a shift happening: there are more people who are angrier, unsatisfied, wanting to see action. Polls show that, over time, Americans have grown increasingly concerned about climate change. This cuts across geography and even cuts across political leanings. But there is still a lack of action.”

Science says that time is running out and urgent climate action is needed, but climate action is falling short. Science is also able to offer solutions, recipes, and suggestions for society to transform itself towards sustainability. If the messages are clear and the solutions are there, why is enacting them so slow? Where are the real barriers to climate communication?

“The political reality is that, although over time Americans have grown increasingly concerned about climate change, the politicians they elect to represent them, their well-being and their values, don’t seem to be reflecting these concerns in meaningful ways. There is also the problem of echo chambers. People become victims of information isolation, because they seek out and repeat narratives and points of view consistent with their beliefs and opinions, regardless of science or lines of evidence that are contrary. Unfortunately, the best climate reporting and climate stories tend to stay inside the more progressive/liberal echo chambers. Conservative audiences tend to not even come across these stories. Or if they are seen, they are misrepresented by pundits or PR people, who give interpretations of these stories that perpetuate their world views.

Moreover, besides the general public and policymakers, climate change awareness must increase within the world of business. Not enough has been done to reach corporate leaders. It seems to me that the two biggest forces against action are conservative politicians and corporations, and corporations have a significant influence on policy in the US.”

When you teach scientists how to explain the results of their research so that they can reach the public at large you recommend using stories.

“The messengers are important. Let’s pick a scientific study about the way that climate is going to impact fishing tourism in the Western United States, for example. You can talk about the risks of how warm waters will reduce stocks of fish; you can explain that people are going to experience economic losses. But if you also talk about how certain towns or certain states are enacting policies to either shift resources to habitat improvement or how to shift business models and provide incentives, then the readers are not just reading about scientists giving projections, or activists pushing for action. People will say: “Oh, there is somebody like me who is worried and who is taking action. I can relate to this person. And if that person is taking action, then maybe I can also consider taking action.”

In general, farmers are going to be at the front-lines of climate change. If you talk to them about shifting crops or better forecasting predictions that farmers in other communities or nearby regions are using, the message might sink in deeper. If they hear about these things directly from other farmers, even better.”

Climate stories can be told through words, but also through images. And you are also a photographer. Historically, climate visual communication has been linked to iconic images such as melting ice and polar bears. Some research demonstrates that the time for these icons is over and that a new visual language for climate change is needed. Based on this evidence, The Guardian is changing the kind of pictures they select to illustrate their coverage of the climate emergency. Why do you think this evolution is needed, and how should climate visual communication be reshaped?

“Photographs have a strong power: they can have an opinion-shifting effect on the public, they can immediately raise consciousness over an issue. I think the issue with the polar bear and some of the other iconic climate-change images of the past few decades is that they are not very relevant to most peoples’ lives.

Climate variability and change is having and will continue to have very real impacts for every person. And perhaps the most relevant impact isn’t what’s happening to the ice sheets. The impact can be how many days in October are hotter now than twenty years ago in the northeast US, for example, and what that means for schoolchildren in overheated classrooms that never needed air conditioning historically, because by the time school started, temperatures were tolerable. Or the increasing frequency of heavy rainstorm events and what that does to public infrastructure, to businesses and homes. Visual communication can and should be more in touch with everyday life.

At the same time, too often our climate visuals communicate emergency, urgency and doom, and I think the risk is that people feel overwhelmed and paralyzed. We need to give people a sense of hope, rather than constant suffering, or death, or dry crops or starving. There is a lot we can do with visual communication to show how people are adapting or trying to adapt to be resilient. I try to focus on that when I report on the work that the International Research Institute for Climate and Society does. Finding contexts where farmers or farming communities are taking an active role in adaptation measures, growing, planting, harvesting, trying out different varieties, participating in trainings, etc.”

Negative stories happen in a world with a changing climate. Natural disasters hit coasts, cities, landscapes. People must face economic losses and impacts on their health. How can we tell these stories without being negative?

“It depends on the context. Climate change is increasingly being linked to disaster and catastrophe. But we shouldn’t focus just on risk, because there are opportunities, too. We can talk about the risks. But we should also show where and how people are trying to manage the risks. In doing so, we can showcase members of the community who might become messengers to their ‘tribes’, such as farmers-to-farmers or business owners-to-business owners.”