by Francesco Bassetti and Davide Michielin

Recent snowfall across Europe should not give way to false hope: Europe is still facing one of the warmest winters since records began. The sparse snowfall has seen grass blanketing the continent’s central mountains, causing concern for the ski industry and winter sports organisers, as well as bringing climate change to the forefront of discussions on the future of skiing.

The chopping and changing of the Alpine Ski World Cup’s calendar is emblematic of the current snow-scarce winter season. In October, the events scheduled in Zermatt (Switzerland) and in Cervinia (Italy) were cancelled due to lack of snow. The following stage, which was originally planned in Zürs (Austria) on November 13, met the same fate. The use of snowmaking machines saved others, such as the surreal slalom trial of January 4 in Garmisch (Germany) that took place on a thin strip of man-made snow surrounded by bright green pastures. As things stand, the upcoming stage in the same Bavarian location, originally scheduled for January 28, has also been moved.

The Alps’ snow cover predictions

It’s not just a matter of professional sporting events. Increasing temperatures and snow-scarce winter seasons challenge the winter tourism industry, one of the most weather-sensitive economic sectors.

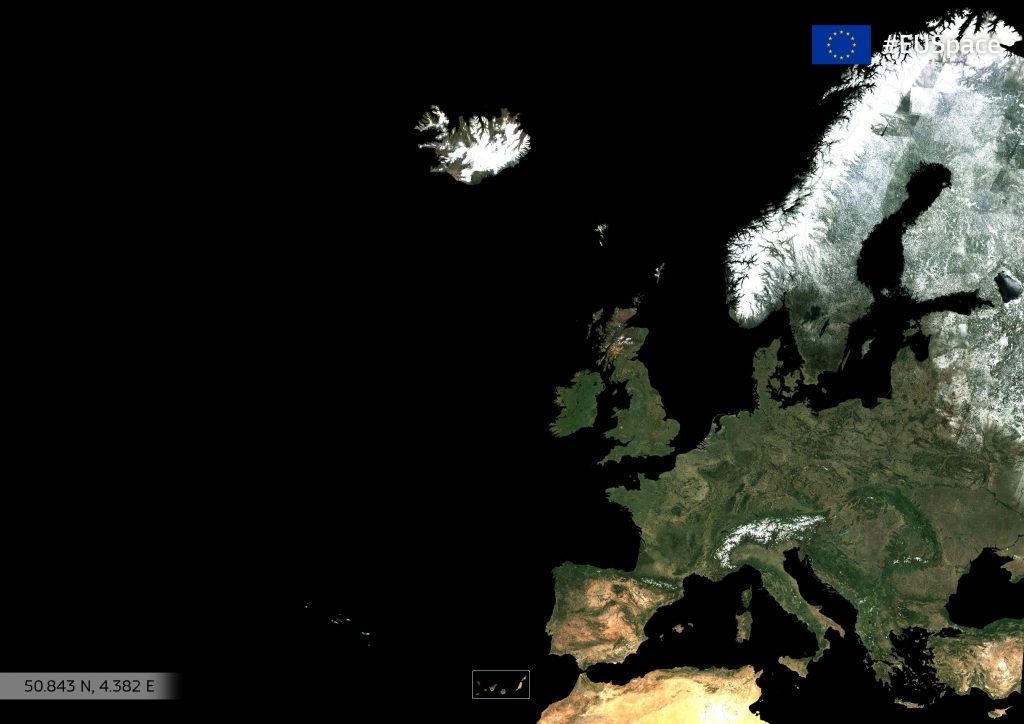

Satellite images have revealed dirty brown hillsides around what should be pristine, white snow-covered ski resorts as record-breaking January heat spread all over Europe. However, climate change is expected to have more material impacts on European Alpine tourism than in other areas of the world.

The Alpine region is going to be as much as three times more impacted by global warming than the average for the Northern hemisphere. According to a study based on tree-ring dating, the recent waning snowpack in the Alps is unprecedented in the last six centuries.

Mild weather has left many locations that would normally be covered in snow at this time of year bare, and winter sports resorts are fearing for the future. Data from the Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research at Davos shows that, by the end of the century, snow may decline between 30 percent and 70 percent in the Alps, affecting even ski resorts that have so far been safe. An estimate that is, by and large, similar for expected glacier mass loss during the same period.

According to EURAC scientists, if climate change is not mitigated, temperatures will increase leading to a change in precipitation patterns, possibly leading to more winter precipitation across the Alps and less in the spring and autumn. However, at lower elevations this precipitation will come in the form of rain instead of snow whereas at higher altitudes, an increase in precipitation might lead to more snowfall in the central winter period. That said, the snow cover season will be shorter because of rising temperatures: snow will accumulate later in fall and melt earlier and faster in spring.

Reports on the current state of affairs

The grim outlook for mountain tourism has pushed the Bank of Italy to face the problem. In the report “Climate change and winter tourism: evidence from Italy”, published in December 2022, the Italian reserve bank analysed 20 years of weather conditions and tourist flows in 39 Alpine ski resorts.

According to consensus projections on climate variables, the experts estimate that in the coming years the impact of climate change on ski passes and overnight stays could be significant, especially at lower altitudes. Moreover, snowmaking might not be enough to sustain tourism flows: while man-made snow can reduce the financial losses from occasional instances of snow-deficient winters, it cannot protect against systemic long-term trends towards warmer winters.

In this context, adaptation strategies based on diversification of mountain activities and revenues are crucial. Considering the potential of a wider set of amenities to sustain touristic flows, investments could be made to reduce the dependence of mountain economy on snow conditions: for example, by enhancing engagement in year-round tourism, stimulating and promoting summer tourism, but also activities and winter weather independent entertainments such as winter trail running races, congress, educational and health events.

Since 2013 the Italian environmental NGO Legambiente publishes a yearly report on how ski resorts are transitioning towards no-snow models across the country. The objective is to advocate for a shift from snow tourism in the Italian Alps and Apennines as climate change brings increasingly warmer and snow free winters.

In the 2022 Report authors renewed their call for a transformation from “Mountains, from mere places of consumption […] into venues for innovative and sustainable experiences.”

The report goes on to highlight 10 virtuous examples across Italy, all of which have in some way brought together sustainability and economic benefits for mountain communities. The initiatives range from promoting year-long tourism – instead of overreliance on the winter season – to promoting alternative activities such as snow shoeing, ski touring, Nordic skiing, or even trekking and mountain biking.

Yet the report also reveals how regional authorities across the Italian Alps and Apennines continue to pour significant portions of their development budgets into further expanding ski lifts and alpine skiing infrastructure. Even in regions that have not historically relied on skiing, such as the Marche region in central Italy a staggering 65 million euros have been allocated to developing ski infrastructure in the Sibillini Mountains.

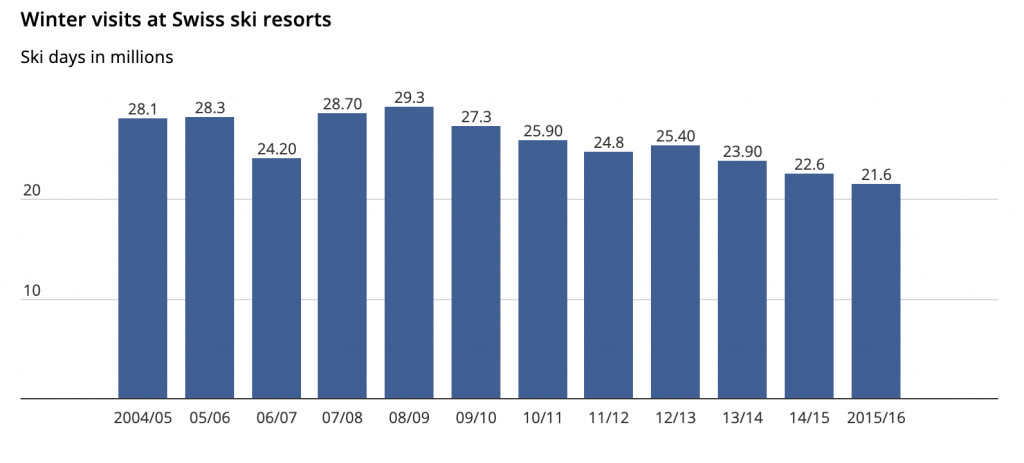

A situation that is also present in Switzerland where two-thirds of the Swiss cable car companies depend on public money for their survival according to a study by the University of Applied Sciences at Lucerne.

Christophe Clivaz professor at the Institute of Geography and Sustainability at the University of Lausanne, and co-author of the book “Winter Tourism: Climate Challenge”, is opposed to this heavy investment approach. “We should focus public subsidies on certain ski areas and help other resorts divest themselves to find alternatives to skiing,” he explains in an in depth interview with swissinfo.ch.

“There isn’t any one activity that single-handedly generates the same income as skiing. But by working on a wide range of diversified alternatives, we can do it. For example, mountain biking and hiking have enormous potential for development in Switzerland. Of course, they do not generate the same turnover as skiing, but the basic investment is also much lower,” Clivaz continues.

A new skin for winter tourism

“The prospects for traditional winter tourism are not good. The decrease in snowfall is one of many issues. For instance, we must consider the permanence of a sufficiently thick layer of snow for at least 100 days a year or, at least, in certain periods of the year such as winter holidays,” says Andrea Bigano, researcher of Economic analysis of Climate Impacts and Policy Division of CMCC.

In the Alps, the only ski resorts likely to survive are the ones found 1,800 metres above sea level. Furthermore, the use of man-made snow will not change the long term situation. “The snowmaking time is up because it requires a huge amount of water and energy. The first limit, in particular, is linked to the growing scarcity of water and therefore to competition with other uses,” adds Bigano, suggesting that next year’s winter tourism must change skin.

Distributing the tourism flows throughout the whole year would be a win-win solution, laying the foundations for a less intensive exploitation of Alps. “Winter tourism is the golden goose of mountain places but it isn’t the only one. Due to Covid restrictions, in the last two years people have reevaluated summer stays. Moreover, the spread of remote working changed the habits of several second-home owners: they spent more time, in different periods, in the mountains than before,” says Bigano.

These different ways of living the mountains requires a change in people’s attitudes and expectations but also adaptation strategies. “Climate change will affect mountains all year round, with impacts on biodiversity, water resources, forests (and hence on forest fire risk). Thus, the transition towards a diversified use of the mountains throughout the year must be coupled with appropriate risk prevention measures and adaptation strategies,” concludes Bigano.

Putting forth solutions

Local operators also recognise this reality. “Mass ski tourism is a thing of the past and we can’t keep fooling ourselves into thinking that it will continue to be as it was,” says mountain guide and ski instructor Michele Comi, who has spent the better part of his life in the mountains, whether this be for skiing, climbing or trekking.

Comi believes that although the local economies of many mountain communities in the Alps have become reliant on skiing there are ways around this. In 2004, Comi became one of the founders of MelloBloccco, a music and climbing festival held in the majestic Val di Mello in the Italian Alps which soon gained global notoriety.

Bringing this event to a small mountain community led to the area becoming renowned around the world for climbing which in turn has led to year round tourism in an area that has traditionally relied on seasonal mass tourism.

“We need to help these mountain communities find their identity and express it in a balanced way,” continues Comi. “Although we will have increasingly less snow, we can still provide people that want to go to the mountains with meaningful experiences.”

A view that was also echoed by Rosalaura Romeo, Programme Coordinator of the Mountain Partnership Secretariat at the Food and Agricultural Association of the United Nations (FAO), in a previous piece written for Foresight, where we took an in depth look at how mountain communities can embark on a more sustainable relationship with tourism through diversification.

What is certain is that if funds continue to be allocated towards developing more and higher ski resorts then mountain areas are embarking on a losing race against the climate. In the words of renowned Italian journalist and writer Michele Serra, “If the winter disappears we can’t fool ourselves into thinking that we can engineer it.”

Cove picture by Lucas Seitz @Unsplash