Recent history counts many examples of failed policy commitments or complete policy reversals. In the climate policy sphere, examples include the rapid and sometimes retroactive withdrawal from clean energy subsidies in the EU, the introduction and subsequent repeal of a carbon tax in Australia and the troubled relationship of the USA with the Paris Agreement.

Failure to meet policy targets is often motivated by the perception of excessively high risks. In the context of the energy transition – which will require an expanding share of private agents to allocate their physical capital investments to carbon-free technologies – firms adopt low-carbon investment strategies only if they expect them to be more convenient than carbon-intensive alternatives. In turn, a major factor affecting their relative profitability expectations is the expected strength and timing of future climate mitigation policies, the most prominent of which is the introduction of a carbon price. What do firms expect future carbon prices to be, and how do they formulate their expectations?

Policy announcements trigger the desired behavioural changes only if individuals believe these will be followed by actual policy actions.

A new working paper, published by the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment (London School of Economics), analyses the dynamic interaction between heterogeneous expectations, investment decisions and climate mitigation policymaking, examining how firms invest in low versus high carbon capital depending on their beliefs about future carbon prices.

The authors show that weak policy commitments, especially when combined with ambitious emission mitigation announcements, produce worse outcomes than less ambitious policy announcements. This can trap the economy in a vicious cycle of credibility loss, carbon-intensive investments and increasing risk perceptions, ultimately leading to a failure of the low-carbon transition.

The authors show that weak policy commitments, especially when combined with ambitious emission mitigation announcements, produce worse outcomes than less ambitious policy announcements. This can trap the economy in a vicious cycle of credibility loss, carbon-intensive investments and increasing risk perceptions, ultimately leading to a failure of the low-carbon transition.

Confronted with multiple sources of uncertainty, individuals develop heterogeneous beliefs regarding the credibility of the policy-maker and the future climate policy intensity, depending on the information they have access to, their ability to process it, the length of their planning horizon, and a number of other behavioural factors.

The power of belief

Beliefs and expectations will also change in time with the arrival of new information, possibly amplified by herd behaviour dynamics or, to the contrary, restrained by deep-rooted convictions creating inertia in the updating process. “In the scarce empirical evidence we have on the matter, expectations about both future climate risks and climate policies, crucial in shaping investments towards alternative technological options, have been shown to be volatile and heterogeneous across economic agents”, premises Roberta Terranova, researcher at RFF-CMCC European Institute on Economics and the Environment (EIEE).

The model she developed with Emanuele Campiglio (Università di Bologna and EIEE) and Francesco Lamperti (Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna and EIEE) incorporates an important real-world dimension. For example, a policymaker who announces forward-looking climate objectives may then renegotiate them if the costs of decarbonisation are perceived to be excessively high. “We already knew that firm investments and policy commitments influence each other. However, as capital investments are long-term, the credibility of the policy makers plays a relevant role in the energy transition: if a policy maker was not resolute in implementing his commitments in the past, one doesn’t expect he will be in the future”, explains Terranova.

However, higher responsiveness to the performance of belief/investment strategies makes firms’ behaviour more volatile, increasing the likelihood of falling into a high-carbon trap, authors found. Another interesting result of the study is that, even when the economic system is directed towards a low-carbon equilibrium, behavioural frictions affect the rapidity of the decarbonisation process in non-linear manners. Finally, belief polarisation can also have non-linear implications on decarbonisation, with higher belief polarisation being beneficial for the transition under certain circumstances.

The results offer several key insights for policy-making. “It is absolutely key for the policy-maker to be aware of what these expectations are and their distribution. And also to be able to orient them as desired: many jurisdictions have shown worrying signs of being unable to maintain their course for sufficiently extended periods of time. A wide societal debate on the most appropriate institutional configuration to achieve long-termist and credible policies is urgently needed”, Terranova concludes.

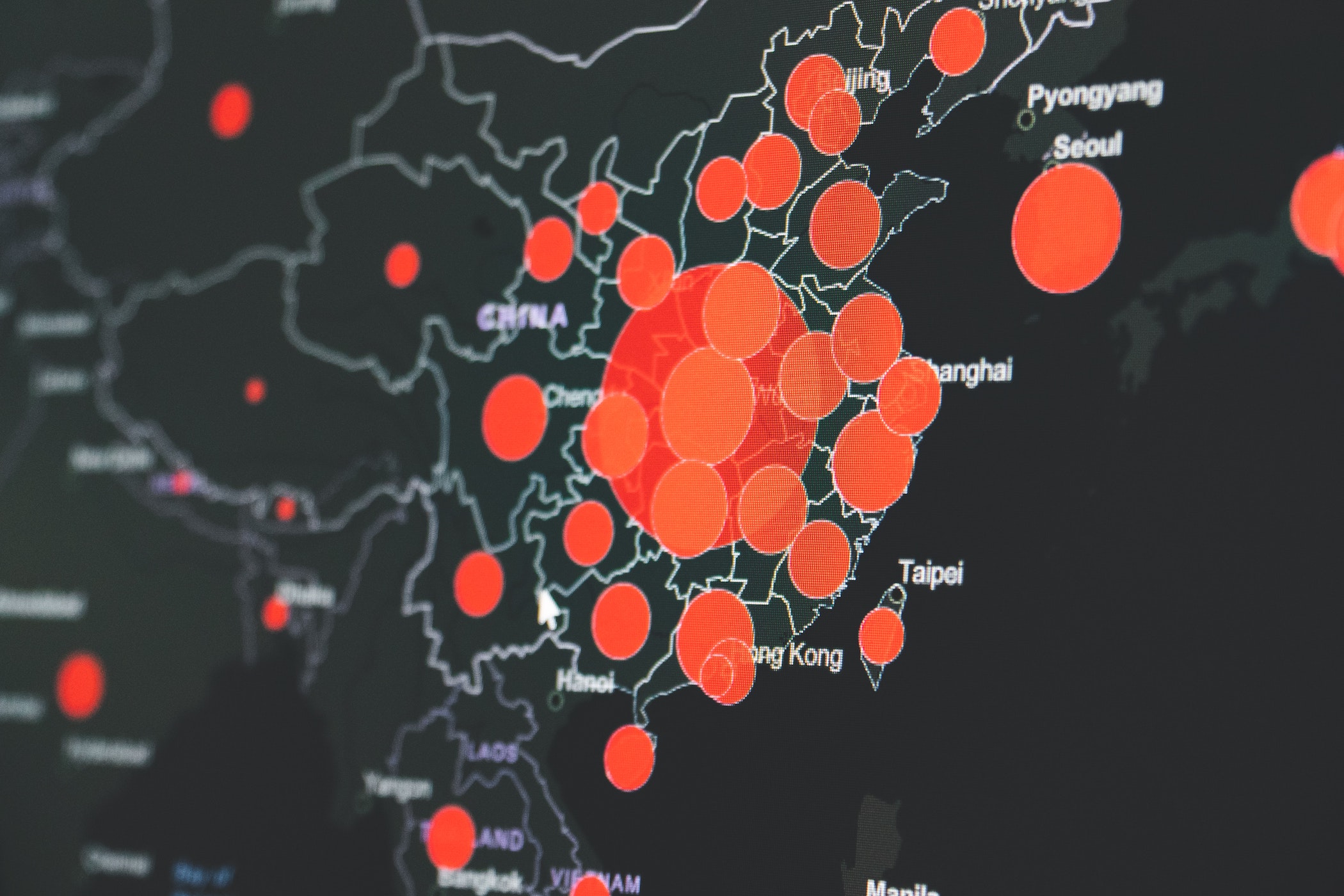

Picture Credits CC from Mika Baumeister on Unsplash