Switch on, switch off. A finger, or even a voice command, is enough to get electricity from the grid at any time. You do not need to worry about when to run your washing machine. You do not even think about where and how the power that lights up your house is produced.

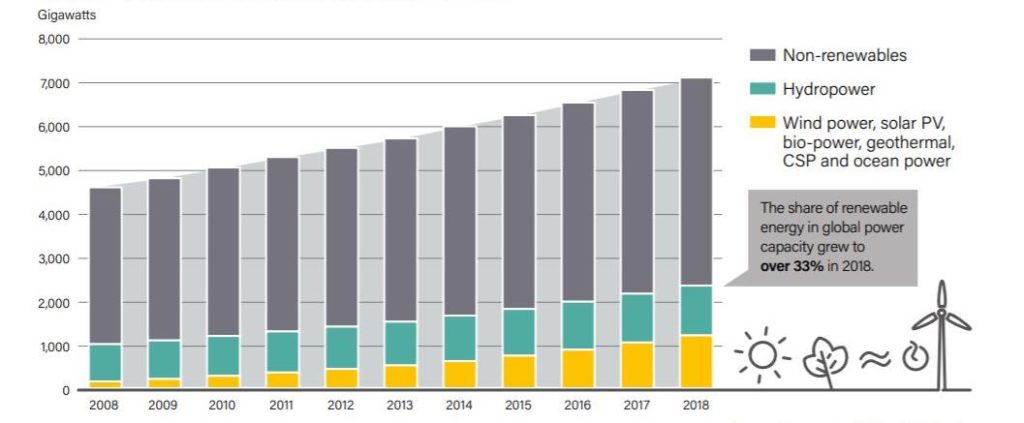

And what would you discover if you were to ask where that electricity comes from? The answer is that globally nearly 78%of energy is still produced by non-renewable sources, according to the latest REN21 report.

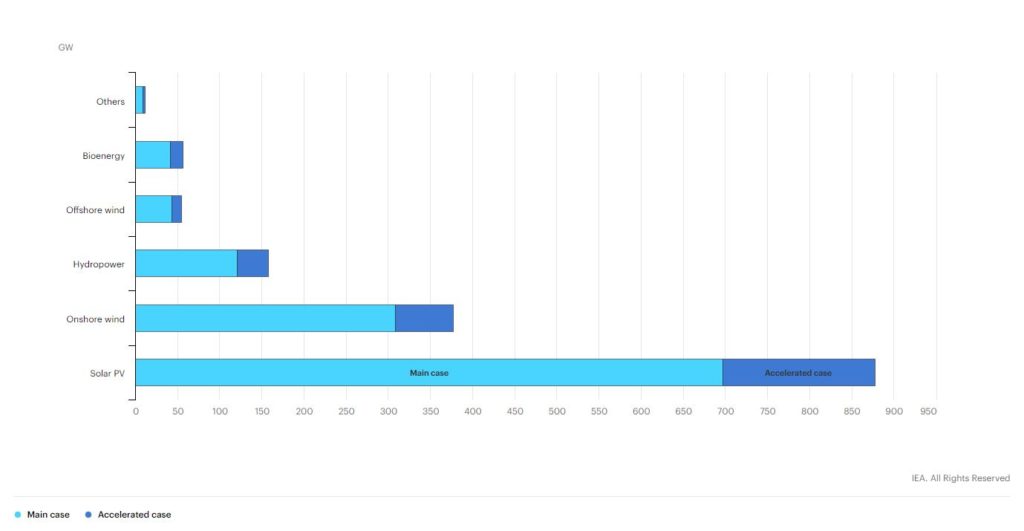

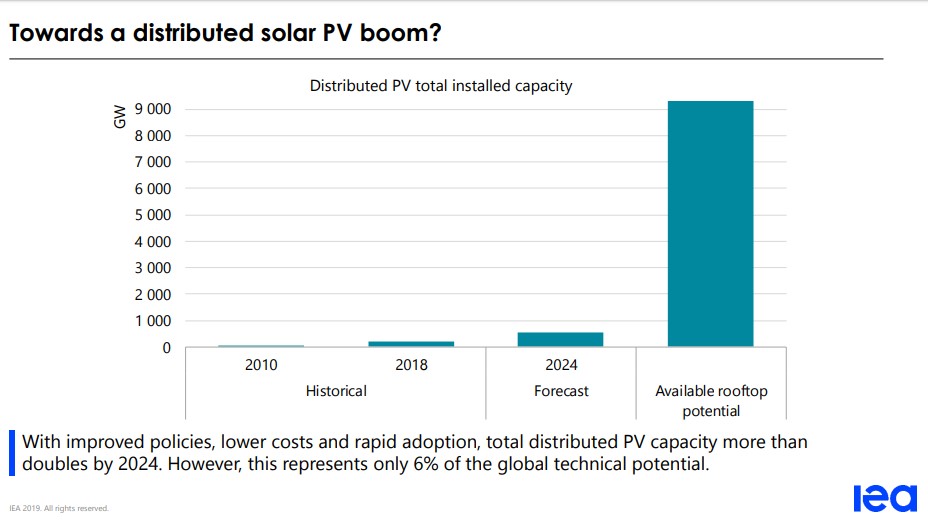

Everyone agrees that an energy system shift towards renewables is urgently needed to tackle global warming and that current trends in energy production and consumption are clearly inconsistent with the internationally agreed Paris Agreement goal of keeping global temperature rise well below 2 degrees by the end of the century. If this long-run perspective can be overwhelming, what the IEA report Renewables 2019 shows about the energy sector in the short term seems quite encouraging and has made headlines. It foresees a renewable power capacity expansion by 50% from 2019 to 2024. The increase amounts to 1200 GW and is equivalent to the total installed power capacity of the US today. This significant – although insufficient – energy system transformation will be led by solar photovoltaics (PV), and followed by onshore wind. Of the additional 697 GW in PV capacity, almost half (320 GW) is due to come from solar PV systems in homes, commercial buildings and industrial facilities. This represents a doubling in rooftop PV capacity by 2024.

THREAD

Today, @IEA publishes its latest forecast for renewables, finding they will grow 50% in 5yrs – and once again that’s faster than expected last year.

They’ll add a giant, US-sized chunk of new capacity, IEA says, or 1,220GW (!)https://t.co/lPWbBTMFn8 pic.twitter.com/silJB7vdGZ

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) October 21, 2019

Distributed renewable generation represents a major change in the energy system because it transforms energy consumers into energy prosumers, namely households and firms which consume energy from the grid for part of the time and produce energy and input it in the grid for part of the time.

And when consumers become prosumers, new opportunities and new challenges unfold in the energy system. How will we get there and what should we expect? What will the world look like with more rooftop panels installed? What barriers must we overcome to sustain this transformation? We asked Elena Verdolini, head of the Sustainable Innovation unit at the RFF-CMCC European Institute on Economics and the Environment (EIEE) and CMCC Foundation, and Assistant Professor of Political Economic at Università degli Studi di Brescia, these very questions.

A story of unanticipated success

“Recent decreases in PV costs have surpassed any sort of projections that we could have made 10, 15 years ago,” begins Dr. Verdolini. “Producing solar panels today can be done at much lower cost than a decade ago, also thanks to cheaper raw materials. We are also gaining experience in integrating solar energy into the system. In many regions of the world, nowadays solar PV is cost-competitive with more traditional fossil sources of electricity generation, and particularly coal-power generation.” According to the IEA, electricity generation costs from distributed solar PV systems will decline by a further 15% to 35% by 2024, making the technology more and more attractive.”

“In the past, IEA projections of the costs and deployment of renewable energy were quite conservative. In the last few years, the IEA has been revising such estimates, as is the case with their latest renewables report. This time they forecast faster deployment in wind and PV installation worldwide,” continues Verdolini. “Yet, the excitement seen in the headlines of the press releases is not completely justified. For instance, the IEA focuses on capacity installed. Yet, each electricity energy source has a specific capacity factor. And renewables have lower capacity factors than fossil fuels. This means that, notwithstanding the significant increase in capacity installed, such capacity can be used to cover a part of the future demand (and future demand increases). Even if capacity increases at the rate forecasted by the IEA, we will fall short of achieving the Paris Agreement. This is indeed very worrisome. Let’s not forget, also, that five years is a very short time for the energy sector. What will happen in the sector by 2024 has mostly already been decided by today’s investment decisions.”

From large-scale to distributed PV systems, mostly on industrial rooftops

IEA data shows that the share of distributed PV is expected to rise from 36% to 45% of total solar PV by 2024, surpassing large-scale photovoltaic systems. Yet, one of the major difficulties linked with solar energy is the inability of storing large amounts of electricity in an efficient way for long periods of time. Solar panels (and wind farms) can produce electricity when the sun shines (and the wind blows). Yet, electricity is also needed when this is not the case.

“Indeed,” comments Verdolini, “if you install a rooftop panel on your business premises or house, you will likely give rise to some behavioral changes. Specifically, by being able to monitor at what time the system produces more power, you will probably be more careful and consume electricity at the time when you are producing it because it is cheaper than buying electricity from the grid when you need it. Yet, this strongly depends on the design of the electricity contracts, which can increase or lower incentives for behavioral change.”

According to the IEA report, householders who will install solar rooftop systems are more than doubling by 2024, reaching about 100 million worldwide. Nevertheless, households will be responsible for only one-fourth of the new installations over the next five years. Indeed, the great majority of new rooftop panels and installations will be on industrial and commercial buildings. The reason is a more stable load profile for these actors compared to residential consumers, which translates into more efficient use of the energy produced and therefore more savings on electricity bills, in addition to economies of scale that lower investment costs.

The role of policy

The growth forecast of the IEA is significant but covers only a very small amount of the actual potential of available rooftops (see figure below). “The deployment of renewable energy is dependent on the implementation of strong policies, which can provide clear incentives to investors and consumers,” clarifies Verdolini. Indeed, as the IEA report shows, if stronger renewable energy policies are in place, the growth of renewables, and particularly solar, could be truly accelerated by an additional 30%.

Policy support is different in different regions of the world and helps shape the numbers and modalities of the distributed PV development. China accounts for almost half of global distributed PV growth and is the largest growth market both for residential and industrial PV. Europe is doubling its industrial and commercial capacity while keeping the residential side stable. North America is second in residential but is surpassed by the Asia Pacific region and by Europe when talking about commercial and industrial PV.

“China will drive growth in the coming years, while prospects for North America are not that good, in line with the fact that the northern part of the continent at present is not so committed to climate action,” affirms Verdolini. “The EU is doing its fair share and is at the forefront of climate mitigation. The IEA forecast somewhat reflects this and the policies that have been put in place at the European level, pursuing a deep decarbonization strategy with a net-zero emissions by 2050 goal. Yet, incentives for renewable deployment are very different in the different members of the EU. In some of them, consumers and firms also have to overcome significant administrative barriers to access subsidies or financing incentives.”

Digitalization and electrification: keywords for the future

“Renewable electricity is a key component of any successful decarbonization strategy, but in fact the problem is much bigger than this,” notes Verdolini. “Electricity generation is where most of the progress has been achieved in the last decade. However, to reach the Paris Agreement goal, decarbonization should now be tackled in hard-to-decarbonize sectors, such as manufacturing industries (e.g. metallurgy and chemical industry) which are still heavily based on fossil fuels. Electrification of these sectors is a key strategy to tackle emission reductions, but not the only one. Significant investments must target new zero-carbon technologies for certain industrial processes that cannot be fully electrified.”

The priorities over the short term should be that of increasing energy efficiency, greening electricity generation, and electrifying all consumption and production process that currently use fossil fuels.

“In any case, the IEA predicts that renewable energy deployment along current trends is not sufficient to achieve the Paris Agreement climate goal of remaining well below 2 degrees. This is a concern for environmental economists as myself, and should be a concern for the wider public. Everyone should be concentrated on how to contribute to the low carbon transition. As discussed in many policy briefs and academic contributions (such as the Final Report of the High Level Panel on the European Deep Decarbonization Pathways), the priorities over the short term should be that of increasing energy efficiency, greening electricity generation and electrifying all consumption and production process that currently use fossil fuels. Becoming prosumers should, therefore, be a priority for all firms and individuals in the short term, and policies should be implemented to support this transition.”

“Digitalization and artificial intelligence are likely to play a crucial role in this respect both with respect to providing novel ways to reduce emissions, and to provide alternatives for economic growth” concludes Dr. Verdolini, who was recently awarded a prestigious European ERC grant for her innovative project focused on the interplay between digitalization and decarbonization. “Much remains to be done. My hope is that the new European Green Deal may, in fact, provide further stimulus for renewable energy deployment.”