From temperatures in the Arctic soaring 40 degrees above average, to extreme flooding along Australia’s east coast, climate change has already left its mark on 2022. As the frequency and intensity of these events continues to worsen, climate change has become a common feature in our news cycle. However, public discourse too often fails to recognise that the burden of climate change will fall unfairly on vulnerable communities. From food insecurity to forced migration, nations including small island states and those on the equator will experience the far-reaching impacts of climate change far more than, and well ahead of, the rest of the world.

Climate justice asserts that we need a post-colonial, human rights-focused approach to climate change in order to address the inequalities it creates. Climate justice seeks to accomplish this in two ways: by recognising that the impacts of climate change are distributed unequally, and by amplifying the voices of disproportionately affected communities (Holmes and Richardson, 2020; Dreher and Voyer, 2014). In short, it aims to establish equality in the distribution of climate change impacts, transfer decision-making authority to those that have and will be most affected, and make their perspectives more visible in political and public spheres.

It is therefore not possible to effectively address climate change without first understanding its social, economic, political and health implications.

What inequalities do frontline communities face?

First, historical disparities in energy use have exacerbated economic inequalities, meaning developed countries such as the United States, Germany and the United Kingdom, are largely responsible for historical emissions. In contrast, nations that have contributed the least to accumulating emissions, will be the most affected by climate change yet have the least resources to invest in adaptation and mitigation. Some of the first to be impacted are Pacific Island nations and Indigenous populations, which has been made clear by numerous vulnerability indices including the Global Climate Risk Index (2021).

For example, despite contributing a meagre 0.006% to global emissions, the Pacific Island nation of Fiji faces sea-level rise, shoreline instability, food insecurity and increasing severity and frequency of extreme weather events. With over 90% living on the coast, and sugar and tourism as their main industries, Fijians and their economy are extremely vulnerable to climate change.

We interviewed Rowena Bullio, Indigenous Facilitator for Australia’s National Environment Science Program’s (NESP) Climate Systems Hub, who spoke to the potential relocation issues faced by low-lying communities in the Torres Strait: “what does this mean for their spiritual connection? Potentially relocating to another place and settling into new communities they may not be familiar with or have support networks in is a very big process.”

The health impacts of climate change are wide ranging. Psychological effects such as chronic fear of environmental collapse and concern for one’s future is encapsulated in the new term ‘eco anxiety’. Physical health impacts include air pollution from bushfires, malnutrition after cyclones and floods, and an increased risk of vector-borne diseases from hotter, wetter conditions. Climate change related extreme weather events also disrupt health services and increase the risk of disease or death among vulnerable populations (Climate and Health Alliance, 2012). These effects are more pronounced in poorer nations. In fact, the World Meteorological Organisation (2021) found that 91% of extreme weather-related deaths occurred in developing countries.

The social, economic and health risks vulnerable populations face are exacerbated by their long-standing exclusion from decision making. Holmes and Richardson (2020) argue that adequate representation of Indigenous communities, people of colour, women and people with disabilities is a precursor for implementing inclusive, effective adaptation and mitigation policies. The underrepresentation of these communities therefore means their experiences and expertise are not utilised in political decision making.

Through the intersection of these matters, frontline communities experiencing the worst effects of climate change are often marginalised and disempowered in centres of power.

How does the media perpetuate these inequalities?

The media plays an important role in how climate change is framed in public discourse, and consequently, how frontline communities are perceived. Much of the work on climate change communication has focussed on how messages can, and have been manipulated through message frames (Lakoff, 2010). Framing involves emphasising specific aspects of a message to establish a context for it, therefore influencing how the public receives that information. Throughout international media, frontline communities are often framed as ‘proof’ and ‘victims’ of climate change.

That is to say the experiences of communities impacted by climate events have been leveraged as ‘eye witness’ accounts or ‘proof’ in attempts to counter climate misinformation (Cameron, 2011). This includes, for example, coverage of world leaders travelling to developing nations to look at the immediate impact climate change is having on the Pacific. Often, this coverage focuses on the broader impacts of climate change in relation to developed nations, as opposed to the welfare of the communities spotlighted (Farbotko and Lazrus, 2012).

Victimhood is another prevalent frame through which communities on the frontlines of climate change are viewed (Dreher and Voyer, 2014). This tends to create an impression that external humanitarian, legal and even financial assistance is required, sidelining how the people and communities themselves understand their experience and in turn, how they wish to respond. In doing so, this also undermines their considerable knowledge and capacity for action.

These frames differ from climate reporting within the regions in focus. This is evidenced in a content analysis conducted by our team at the Monash Climate Change Communication Research Hub (MCCCRH) on the reporting of climate change in nine Pacific Island nations. The analysis found that more than 26% of newspaper reports framed Pacific Islanders as global leaders, and more than 17% used resilience and empowerment narratives. In contrast, less than 1% framed Pacific Islanders as victims. This demonstrates that Pacific Islanders see themselves as leaders in the international space who are empowered agents of change, which is in direct contrast to how other countries report on the issues they face due to climate change. Pacific Climate Partnerships Outreach Officer Kateia KeiKei challenged the media to “portray us as human beings, as real people with dignity and dreams for the future” (Dreher and Voyer, 2014).

In addition, research has found those on the frontlines of climate change often feel that their voices are rarely heard and if so, seldom listened to (Kelman, 2010; Paton & Fairbairn-Dunlop, 2010; Ryan, 2010). Rowena Bullio echoed this concern, stating “I don’t think there is enough messaging around Indigenous people and climate change.”

Consequently, the media further perpetuates the aforementioned climate justice issues, with those communities that are first impacted often left as the last heard.

How can climate communication address these inequalities?

There are three communication strategies that assist in addressing climate change as a social justice issue: localising the information, amplifying community perspectives, and consulting with impacted groups.

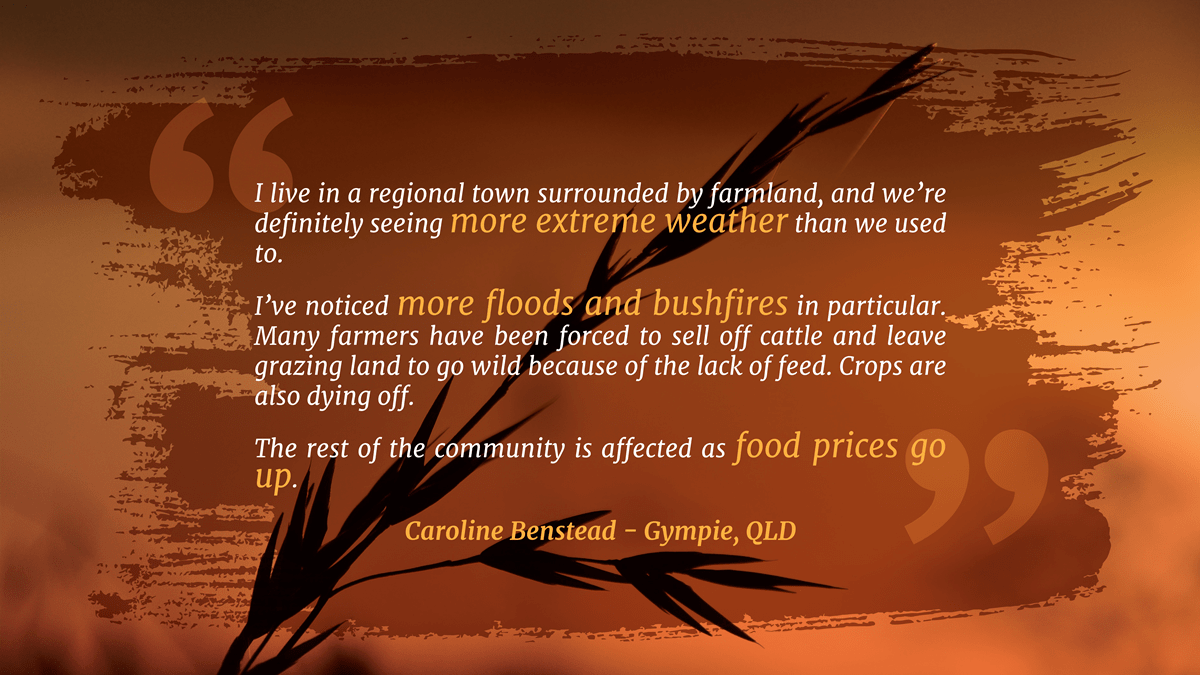

In our study of Australian television audiences, 91% of the 750 respondents expressed a preference for local climate information over that with a global focus (Holmes and Hall, 2020). The importance of localising climate information extends beyond television audiences and applies to all communication avenues. Scannell and Gifford (2011) found that media messaging should “illustrate the local and regional impacts of climate change because these may be more captivating than global impacts”. This is because the impacts of climate change are often perceived as abstract, occurring far in the future and not related to our daily lives. However, when messages include a local context through data or imagery, audiences feel the information is more personally relevant, resulting in higher engagement. Tapping into our sense of connectedness to place is a powerful tool when making an abstract concept like climate change more accessible, and helps to answer questions such as “what does this mean for my community and loved ones?”.

Second, but parallel to localising information, is the importance of amplifying community perspectives. Not only does this assist in humanising the complex topic of climate change, but it also ensures the media is capturing the diversity of voices of those experiencing, adapting to and mitigating against climate change. We can therefore capture the spectrum of experiences including the struggles individuals face, as well as their inspiring and empowering work. This ensures messaging is not one tone that perceives them solely as ‘proof’ or victims. It also gives an opportunity to highlight Indigenous Knowledge in addressing climate change. As Rowena Bullio stated, “Indigenous Knowledge is very holistic in nature, with connection to land and sea and air. There are tangible outcomes that can be transferred to other communities through consent and other processes, which would be very beneficial, especially to local and remote communities which may be quite susceptible to the negative impacts of climate change.”

It is crucial that this is done in consultation and collaboration with the impacted person(s):

MCCCRH flagship program Changing Climates is an example of how media can operationalise these findings. Changing Climates produces hyperlocal content for digital news audiences across Australia. Two key components of every article are a graphic analysing a local climate trend, and an interview with a community member. The MCCCRH synthesises data from hundreds of weather stations across the country to identify significant monthly and seasonal climate trends in each publication region. In doing so, audiences can receive information relevant to them and see exactly how their region has changed over time. In addition, this information is paired with comments from a community member such as a parent, farmer, firefighter, nurse or business owner, discussing how they are experiencing climate change. This approach humanises climate information and amplifies the voices of those experiencing its impacts, therefore ensuring we are hearing directly from those affected.

By employing these strategies, media infrastructure can communicate information that accurately and respectfully captures the voices of those experiencing the impacts of climate change. In doing so, communication will no longer exacerbate the inequalities that have been perpetuated by the majority of media focusing so heavily on national interests and political ping pong.

While the media has served to propagate injustices in the past, it also has the power to shape the climate conversation in the future. Therefore, instead of politics shaping media reporting, reporting can instead shape politics. In doing so, the media can serve as ‘watchdogs’ by holding decision makers accountable to the voices of those most vulnerable.

In summary, in order to address the broad range of inequalities exacerbated by climate change, it is essential that we examine how we frame and disseminate related information. By communicating climate change impacts in ways that are relevant and accessible, and by passing the microphone to those most at risk, we can improve representation in both reporting and decision making.

The Hub’s project Changing Climates – a science-based, data driven weekly column published in Australia’s leading online news sites – has been shortlisted as one of the best climate communication projects running for the CMCC Climate Change Communication Award “Rebecca Ballestra” 2021.

Ella Healy is the Operations Manager at the Monash Climate Change Communication Research Hub. Ella holds a Bachelor of Health Science from Deakin University and a Master of International Relations from Monash University.

In her role, Ella manages the Changing Climates and Climate Communicators programs which aim to increase public understanding of climate change by disseminating climate science in accessible formats across television and digital news outlets.

Ana Ross is a Senior Project Officer at the Monash Climate Change Communication Research Hub. Ana holds a Bachelor of Science Advanced – Global Challenges (Honours), focussed on the application of science, leadership, and entrepreneurship to solve complex challenges.

At the Hub, Ana works on communicating climate science in accessible and meaningful ways through the Changing Climates program.

Finally, a thank you to Rowena Bullio who contributed her ideas and knowledge to this article. Rowena is the Indigenous Facilitator at the Climate Systems Hub, which is funded by the Australian Government under the National Environment Science Program.

References

Cameron, F.R. (2011). Saving the ‘disappearing islands’: Climate change governance, Pacific island states and cosmopolitan dispositions. Continuum, 25(6), pp.873–886.

Dreher, T. and Voyer, M. (2014). Climate Refugees or Migrants? Contesting Media Frames on Climate Justice in the Pacific. Environmental Communication, 9(1), pp.58–76.

Farbotko, C. and Lazrus, H. (2012). The first climate refugees? Contesting global narratives of climate change in Tuvalu. Global Environmental Change, 22(2), pp.382–390.

Climate and Health Alliance (2012). Health Sector Ill-Prepared for Climate Change. [online] Melbourne: Climate and Health Alliance. Available at: https://www.caha.org.au/health_sector_ill_prepared_for_climate_change_lsuzmkewglvg7jj_let0j.

Eckstein, D., Künzel, V. and Schäfer, L. (2021). Global Climate Risk Index 2021: Who Suffers Most from Extreme Weather Events? Weather-Related Loss Events in 2019 and 2000-2019. https://germanwatch.org/sites/default/files/Global%20Climate%20Risk%20Index%202021_1.pdf. German Watch.

Holmes, D. and Burgess, T. (2019). Climate Change Communication in the Pacific Islands. Melbourne: Monash Climate Change Communication Research Hub.

Holmes, D. and Hall, S. (2020). A survey of Australian TV audiences’ views on climate change: Key Findings. Melbourne: Monash Climate Change Communication Research Hub.

Holmes, D. and Richardson, L. (2020). Research Handbook On Communicating Climate Change. S.L.: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Kelman, I. (2010). Hearing local voices from Small Island Developing States for climate change. Local Environment, 15(7), pp.605–619.

Lakoff, G. (2010). Why it Matters How We Frame the Environment. Environmental Communication, 4(1), pp.70–81.

Paton, K. and Fairbairn-Dunlop, P. (2010). Listening to local voices: Tuvaluans respond to climate change. Local Environment, 15(7), pp.687–698.

Ryan, Y. (2010). COP 15 and Pacific Island states: A collective voice on climate change. Pacific Journalism Review: Te Koakoa, 16(1), pp.192–203.

Scannell, L. and Gifford, R. (2011). Personally Relevant Climate Change. Environment and Behavior, 45(1), pp.60–85.

UN Women (2021). Facts and figures: Leadership and political participation. [online] UN Women. Available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/leadership-and-political-participation/facts-and-figures.

Zander, K.K., Petheram, L. and Garnett, S.T. (2013). Stay or leave? Potential climate change adaptation strategies among Aboriginal people in coastal communities in northern Australia. Natural Hazards, 67(2), pp.591–609.