Earth is under pressure. With growing global population and well-being, natural resources are overexploited, energy demand is rising, garbage and pollution are often uncontrolled, landscapes are changing. We are borrowing resources from the future, as we are consuming more than what the Earth system can produce, and we are producing more waste than it can absorb.

Human beings are the driving force of a new phase of planetary history: the Anthropocene. And, while scientists are investigating whether this term can officially identify a new geological era in recognition of profound and lasting human changes to the Earth’s system, we can already witness what it looks like.

A privileged point of observation is offered by the Anthropocene art project, which bears witness to the effects of the human footprint on natural processes through the photographs of Edward Burtynsky, films by Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier, and immersive augmented reality installations.

Our planet has borne witness to five great extinction events, and these have been prompted by a variety of causes: a colossal meteor impact, massive volcanic eruptions, and oceanic cyanobacteria activity that generated a deadly toxicity in the atmosphere. These were the naturally occurring phenomena governing life’s ebb and flow. Now it is becoming clear that humankind, with its population explosion, industry, and technology, has in a very short period of time also become an agent of immense global change. Arguably, we are on the cusp of becoming (if we are not already) the perpetrators of a sixth major extinction event. Our planetary system is affected by a magnitude of force as powerful as any naturally occurring global catastrophe, but one caused solely by the activity of a single species: us.

Edward Burtynsky, photographer

The multidisciplinary exhibition makes its European debut at Fondazione MAST, Manifattura di Arti, Sperimentazione e Tecnologia in Bologna, Italy, inviting viewers to reflect on the deeper meaning of what these profound transformations signify. The exhibition, open until January 5, 2020, is curated by Urs Stahel, Sophie Hackett, and Andrea Kunard and it is organized by the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto (AGO) and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa (NGC) in partnership with Fondazione MAST.

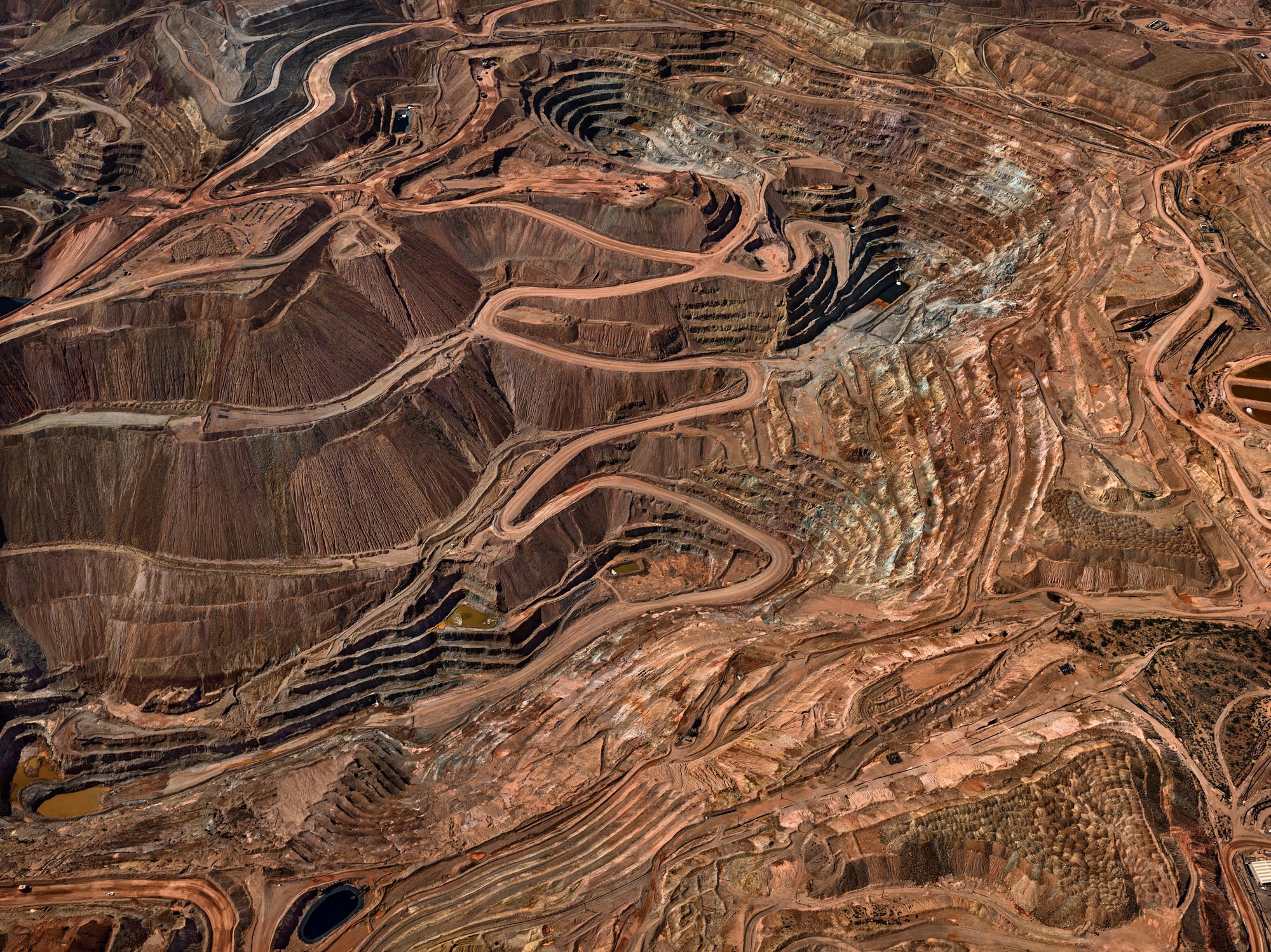

Anthropocene documents the indelible human footprint on planet Earth. From concrete seawalls in China that now cover 60% of the mainland coast, to the biggest terrestrial machines ever built in Germany, to psychedelic potash mines in Russia’s Ural Mountains, to the devastated Great Barrier Reef in Australia, and surreal lithium evaporation ponds in the Atacama desert, from the marble quarries in Carrara to one of the world’s largest landfill sites in Dandora, Kenya.

In an immersive experience, the audience is brought to an awareness of the normally unseen result of civilization’s cumulative impact on the planet.

In his photographs, Edward Burtynsky’s lens also captures natural resource extraction processes and oil bunkering in the Niger Delta, deforestation, large transport infrastructures, copper and coal mines, many different forms of pollution, phosphor tailings ponds, brackish water wells, solar and wind power plants, oil refineries, petrochemical plants, huge greenhouses and desertification scenarios.

An integral part of the MAST exhibition is the award-winning feature documentary film ANTHROPOCENE: The Human Epoch, co-directed by the three artists. Third in a trilogy that includes Manufactured Landscapes (2009) and Watermark (2013), the film brings a provocative experience of our impact on nature.

Just the word Anthropocene opens a new understanding, a different way of looking at things

Nicholas de Pencier, filmmaker

The film, gathering proof from 44 locations in 22 countries, shows a constant dialectic between scale and details, where big pictures are followed by little narratives. The audience can see the origin of common consumer goods, discovering where raw materials come from and how their extraction changes and impacts natural landscapes.

The relationship between scale and detail is the most important thing […], formally. Without an understanding of scale, you can get lost in detail, but without the detail, you don’t understand the meaning of the scale. Because you can’t understand watersheds if you’re not up high. But there’s a danger of floating away and not engaging. This goes back to the ethical thing: you have to be on the ground to understand a place. So in “Anthropocene,” yes, we want the big view of Lagos, but yes, we want to be on the street, on the back of a motorcycle or following people in the market.

Jennifer Baichwal, filmmaker

Photos: © Edward Burtynsky. Courtesy Admira Photography, Milan / Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto