“Every electoral cycle where we don’t vote governments that are positive about acting on climate change is wasting time that we don’t have.” This is, loud and clear, the starting point of a reflection on how choosing the right messages and how to communicate them can have a serious impact on the future of a country, and consequently of the whole planet.

The quote comes from a CMCC webinar featuring Rebecca Huntley, one of Australia’s foremost researchers on social trends, whose title is the question “How to talk about climate change in a way that makes a difference?”.

The 2019 Australian federal election was dubbed by the media “the climate election”, due to the established public polling showing clearly that climate change was a real concern for Australians, and the common feeling was that the government should have been more serious about it.

The first Australian climate election

During the webinar, attended by more than 200 people, Huntley described the communication campaign organized by climate movements leading up to the 2019 elections in Australia. The campaign focused on opposing the Adani coal mining projects in Queensland, which was considered extremely problematic for climate change and destructive to the natural environment. At the time, a widespread belief was that “2019 could see the end of a conservative government that wasn’t taking climate change seriously,” according to Huntley, “and the Adani campaign would actually not only boost the vote for the greens but help leverage the labor party that had slightly better climate policies into government.”

But reality did not meet expectations. The results revealed the election of a prime minister “who brought a lump of coal into the parliament when he was the Treasurer, waved it at the prime minister and said ‘this is coal, don’t be afraid of it’.”

Indeed, the election outcome led to a reflection within the climate movement about their strategies of communicating the urgency of climate change to the population, that is, to voters. “2019 was an extraordinary shock,” said Huntley. “It really brought about a significant reflection and rethinking from the climate movements about who they was speaking to, and about how they needed to communicate. [The fact that the polling showed that Australians were really concerned about climate change and the election results seemed] a disconnect they had to understand.”

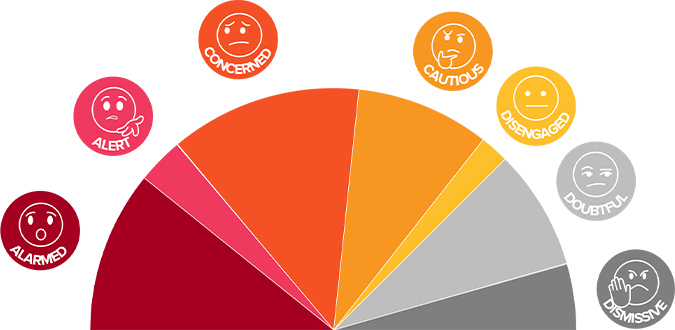

At that point, Huntley began working on analyzing the dynamics that led to the failure of the 2019 “climate election”, and on researching different, more positive and effective messages. She came across Yale University’s Six Americas framework, that divided the American public into six segments based on their beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors associated with climate change, namely: Alarmed, Concerned, Cautious, Disengaged, Doubtful, and Dismissive. “The idea that you have different kinds of audiences, and that you would need to really deeply understand them in order to find a way to communicate with them about climate made a lot of sense to me,” said Huntley.

The Climate Compass takes inspiration from the Six Americas study, focusing on the Australian landscape. Created as an initiative of the Sunrise Project, it “builds a comprehensive understanding of attitudes Australians hold on climate change and how people are prepared to take action,” and tries to answer crucial questions: How do people feel, think and act when it comes to climate change? How can communication be tailored to motivate action?

The Climate Compass

The Climate Compass divided Australians into seven segments based on their attitudes and values towards climate and government actions. The study “has been incredibly successful,” said Huntley, “it was used as the guiding framework for the entire climate movement leading up to the new election in 2022.”

Among the segments in the Compass, the alarmed and the alerts combined represent 30% of the population. They are typically people who not only care about climate, but take action, for example voting for parties that are really committed to take action for climate.

“What we realized with these analyses was that who we really needed to shift were the audiences in the middle,” said Huntley. “People who think climate change is an issue, want governments to do more, but often don’t act on it, they’re not necessarily voting on the basis of climate, and really understanding their mindset and communicating to them was seen as absolutely critical to be able to shift the politics, and shift the national discussion around climate.”

As Huntley recounted, the climate movement in Australia did an enormous amount of work oriented by the Climate Compass, focusing on concerned and cautious audiences and thinking about new messages that could connect with their values, mindset, and hopes for their well-being.

“We were working a lot in the lead up to the 2022 election because there was a lot at stake,” said Huntley, “and it was clear very early on that the climate election that we were supposed to have in 2019, had actually arrived in 2022.”

“How to talk about climate change in a way that makes a difference” is the first in a series of online events labelled Foresight Dialogues in which writers, artists, journalists, scientists, innovators and entrepreneurs discuss the role of communication, in its various forms, in accelerating the climate transition. The Foresight Dialogues series is organized in the context of the CMCC Climate Change Communication Award “Rebecca Ballestra” initiative.

Rebecca Huntley is one of Australia’s foremost researchers on social trends. She holds degrees in law and film studies and a PhD in Gender Studies. She has led research at Essential Media and Vox Populi and was a director at Ipsos Australia. For a number of years, she ran her own research and consultancy firm working closely with climate and environment NGOs, government and business on climate change strategy and communication. She is now Director of Research at the agency 89DegreesEast. Author of numerous books including How to Talk About Climate Change in a Way that Makes a Difference (Murdoch books, 2020), Rebecca was also a broadcaster with the ABC’s RN and presented The History Listen and Drive on a Friday. She writes regularly for The Monthly and Australian Traveller Magazine and has written op eds for The Guardian and The SMH. She is the Chair of the Advisory Board of Australian Parents for Climate Action. She is a member of the Advisory Group for the Climate Solutions Centre at the Australian Museum and the Sydney Environment Institute. She has held board positions on the board of The Bell Shakespeare Company, The Whitlam Institute and The Dusseldorp Forum. She was an adjunct senior lecturer at the School of Social Sciences at The University of New South Wales.

More information: