In this episode, we follow the water. In China, in front of the Three Gorges Dam, the largest on the planet, both the force of nature and the power of man to shape and mould landscapes are on show.

We follow the water in Egypt, at the meeting point between the Middle East and Africa, venturing down the Nile, a river that has accompanied man since the beginning of ancient civilizations and that still today is synonymous with life for the entire region.

We continue to follow the water in its journey from Venice to Alexandria, from the legacy of Ancient Rome to the American Republic and the British Empire, up to the modern era and the “hydraulic century”, where institutions are shaped by the relationship between man and water.

Join us on this journey with scientist Giulio Boccaletti, author of the book “Water. A Biography”, and Rehab Abd Almohsen, Egyptian science journalist and water expert: two voices that will help us understand the key role of water in the future and in the build-up to COP27.

Foresight – Deep into the Future Planet, a podcast produced by the CMCC and FACTA.

Giulio Boccaletti, Ph.D., is an author, entrepreneur, senior executive, and a globally recognized expert on natural resource security and environmental sustainability. Trained as a physicist and climate scientist, he holds a doctorate from Princeton University, where he was a NASA Earth Systems Science Fellow. He has been a research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a partner of the global consulting firm McKinsey & Company and a leader of its sustainability practice, and the chief strategy officer of The Nature Conservancy, the largest environmental organization in the world.

Giulio Boccaletti, Ph.D., is an author, entrepreneur, senior executive, and a globally recognized expert on natural resource security and environmental sustainability. Trained as a physicist and climate scientist, he holds a doctorate from Princeton University, where he was a NASA Earth Systems Science Fellow. He has been a research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a partner of the global consulting firm McKinsey & Company and a leader of its sustainability practice, and the chief strategy officer of The Nature Conservancy, the largest environmental organization in the world.

His book, Water: A Biography, published by Pantheon Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House, was named by The Economist as one of the best books of 2021, and has been translated in multiple languages. He writes on environmental issues for news media, and is an expert contributor to the World Economic Forum, which named him one of its Young Global Leaders. He routinely contributes to documentary series. His work on water has been featured in the PBS documentary series H2O: The Molecule that Made Us. He was also series consultant to the PBS/BBC series The Age of Nature. He is the co-founder of Chloris Geospatial, a venture-backed company that uses remote sensing and machine learning to help companies and institutions put nature on the balance sheet. He is an Honorary Research Associate in the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment at Oxford University and a Senior Fellow of the Euro-Mediterranean Centre for Climate Change. He lives in London.

Rehab Abd Almohsen is an Egyptian freelance science journalist based in Cairo. She regularly writes for SciDev.Net and Scientific American.

Rehab was awarded three at the Nile Media Awards ceremony this year, in the categories of Digital, Print and Best Female Entry.

A former editor at Scientific American, Rehab is also a media trainer who provides multiple pieces of training on science journalism, water reporting and covers climate change issues for the International journalists’ Network (IJNET), Al Jazeera Media institute, the British Council, and others. Rehab is also among the authors of Water conflict and cooperation, a media handbook.

Her work on Nile River-related coverage has also led to prizes sponsored by SIWI, International Centre for Water Cooperation, and the European Union.

Podcast transcript

Rehab Abd Almohsen: “We are not lacking technology. We are not lacking the ability and we are not lacking water, by the way. We are lacking cooperation.”

Giulio Boccaletti: “Our choices about the landscape and about water are really choices about ourselves, about our liberties, about who gets to decide what, where. Who gets to decide what you see when you look outside the window. That question is central to how we’re going to move forward managing a different world environment.”

“On July 19th, 2010, a Monday evening, water came crashing down the Yangtze River. Intense rain from the East Asian monsoon hit southwest China. Water poured from the sky. As Monday turned into Tuesday, the flood roared down: every second, seventy thousand cubic meters of water came through, equivalent to thirty Olympic-size swimming pools.”

This is how the prologue of the book “Water: A Biography” begins. The author is the Italian-English climate scientist Giulio Boccaletti. He starts his fascinating journey through the history of water from the Yangtze, a river that has played a major role in the history, culture, and economy of China. In 2010, a violent flood hit the river against the largest dam ever built: the Three Gorges Dam.

Giulio Boccaletti: “Three Gorges Dam is an archetype, right? It’s by far the biggest dam on the planet. And in many ways, it sort of encapsulates a lot of the themes of the book, the expression of the power of the state on the landscape vis-a-vis the force of water. So that’s why I started there.”

During the flood, the water level rose by four meters. But the Three Gorges Dam held, averting a disaster. It had passed its first real test. “The dam seemed to prove that those living downstream could sleep soundly in the knowledge that something powerful watched over them”, Giulio Boccaletti writes.

Giulio Boccaletti: “China happens to be the, you know, the plumber in chief of the world at the moment. If you were to ask which country in the world is responsible for the greatest modification of water systems around the world? It’s probably China both because it has completely transformed the hydrology of China itself and because it’s offered its services to a number of developing countries around the world.

I am Elisabetta Tola, science journalist, and this is Foresight – Deep into the Future Planet, a podcast produced by the CMCC Euro-Mediterranean Centre on Climate Change and FACTA.

Today, we travel through the history of water. We follow the water to understand its relationship with human civilization, and we look at the water through the eyes of people studying and reporting and being affected by water.

The Three Gorges Dam is an iconic example of human modern attempts to control water. Being the plumber in chief of the world, China is also spreading a particular idea of how the landscape should be transformed. But history tells us that water management is always provisional. In the past years and months, the Three Gorges Dam itself proved to be less invincible than was once thought.

As is often the case, in order to understand what’s happening today we need to start from the past. Water’s biography by Giulio Boccaletti presents water as a character crossing space and time. The real story begins 10 thousand years ago, with the first sedentary civilizations. People started “Standing still in a world of moving water”, and this contributed to shape the first human institutions.

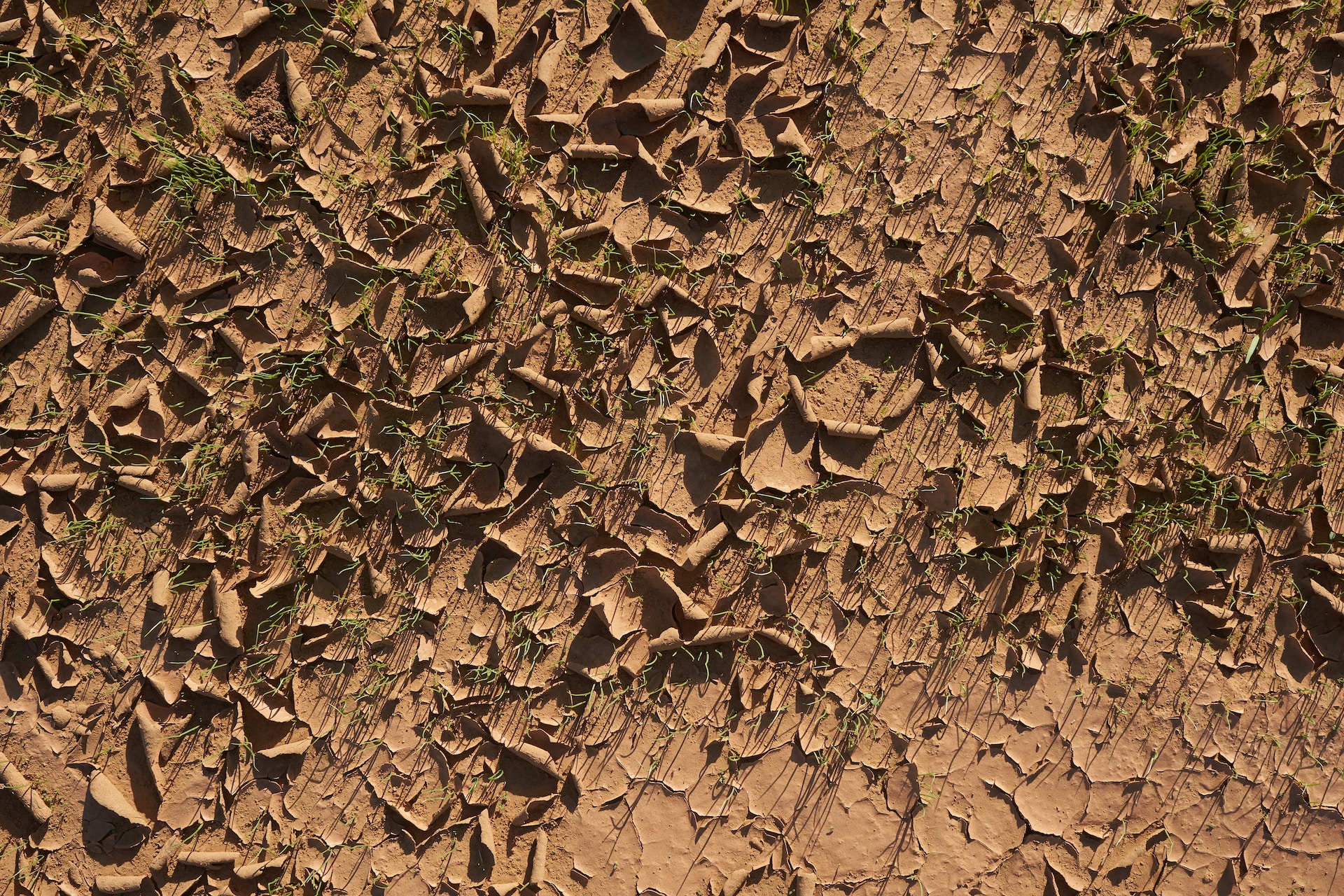

Giulio Boccaletti: The basic element of my argument is that, you know, during the Neolithic revolution, we become essentially sedentary farmers. Those first experiments in sedentary agriculture that happened first in the Levant and then in Mesopotamia, eventually out populate the rest of the world. And the peculiarity of being a sedentary society that’s essentially creating an artificial ecosystem for food production, as agrarian societies are, is that you have this important problem, which is suddenly when you stand still and you know longer move around with ecosystems as they adjust to different climates and water conditions, you find yourself having to confront the other big force on the landscape. The other thing that does work, physical work on the landscape, on timescales that are relevant to human beings, and that is water in all of its expressions. That is water through floods, through storms, through the absence of water and therefore droughts, water as the expression of the climate system, as the principal agent of the climate system.

And so inevitably a sedentary society has to organise to exercise collective agency on the landscape. You know, you have to build levees. Well, that’s a collective action. You can’t just have one person trying to do it. They’ll never reach the scale required to manage the flow of the Tigris. You have to build dams. You have to, you know, dredge canals. For these large, even early infrastructural projects require, you know, the organisation of labour requires, you know, basic institutions to coordinate the agency of individuals into a single agency, a collective agency of society.

When it comes to human society, rivers have the richest and most ancient stories to tell. A great example in Boccaletti’s book is a story that we actually study at school in any history book: Egypt. The great civilizations around the Nile river have been shaped and formed by water over time.

And this is true even today. Rehab Abd Almohsen, an Egyptian science journalist who has been covering climate change for many years, knows that very well. As Giulio Boccaletti, she also follows the water.

Rehab Abd Almohsen: “The Nile for Egyptians it’s different than any other river in any other place because all the countries I know they have at least more than one river or don’t have any rivers at all like Saudi Arabia. So they are very accustomed, they are very used to not have a surface of freshwater. But for Egyptians, this civilization, the civilization that you mentioned, the ancient Egyptians, they built this civilization because of the Nile. And around the Nile, the Egyptian population are living literally beside the Nile. So if you check the Egyptian map, you will find a thin green line that is cutting Egypt from up to down, from the southern part of Egypt to the Mediterranean. This is the Nile. And we all are living in this small surface, 90% or 80, 85% of the country is a desert region that is almost not used. The Nile is literally the blood vessel of the country. And without the Nile, there will be no Egypt. So the country will be 100% desert. We are dependent on the Nile for our food, for our drink, for everything. We don’t have rain. We are a very dry country. It rains once a year or twice a year, I think, in Cairo. So this is the Nile. Just to give you a glimpse on how the Nile is in every song, in every national song. For Egyptians, it’s a source of root and source of everything – like, this is our life.”

Today, this treasure is at risk. As Rehab points out, the climate crisis is hitting the Nile, just like many other crucial water sources in the world.

Rehab Abd Almohsen: “When you have this kind of long relation to something, even if this something is very vital and very important, such as the Nile, sometimes you take it for granted. So I can see that in some places the common attitude is not raising to the level that should be, that we are not treating the river in this holy place that it should be treated with. We are not keeping it healthy and trying to maintain it. But on the other hand, this happened for a long time but I think this is changing during the last ten years, maybe with the threat that came with the Ethiopian dam and the bringing of the Nile into the media, more and more people are not taking it for granted anymore. People understood that this relation that we have through our history during these thousands of years, that with the Nile might be jeopardized a little bit. It might not last for another thousand years. So with the effect of climate change and other threats, I think the relations with the Nile will have some ups and downs. And I think we are in the process of enhancing this relation at the moment.”

Enhancing people’s relationship with the Nile means putting in place tailored conservation actions. This, and more in general water, will be one of the hot topics of Cop 27, kicking off in November 2022 in Egypt. And Rehab is looking at this very closely.

Rehab Abd Almohsen: “Egypt wears two hats. It’s both a middle eastern country and an African country, and both continents are suffering from water issues and also problems in slightly a different way. So in Middle East, this is the most scarce region when it comes to water and the water topic, bringing a lot of noise and conflict, if we may say so. You can see the Nile and what’s going on, on the Nile and the conflict we are having with some of our neighbours because of the water and climate change and the future of this river, and this is one aspect and we have also in Iraq and the problem with their neighbours. So the water issue is a very hot topic at the moment, and it will be the hottest topic in the future.

So this COP is trying to focus on water. They have a special day for water. Water is included in some other days, like the energy and the food and agriculture. And they say that water is a real focus in the food and agriculture and this is the first time to address agriculture in Cop.”

After COP26 and towards COP27, we hear more and more of solution-oriented approaches to the climate crisis. But the scientific community is still quite sceptical about the impact of local solutions to global problems. What is really needed, as Rehab highlights, is cooperation.

Rehab Abd Almohsen: “One of the solutions that I find to be very interesting, and I hope it is not very idealistic, is all of them in general, are related to cooperation. One hand will not clap. We need to cooperate. There is no other option. As I was saying, we have the Nile as a good example that all that we need to have enough water for all the Nile countries is cooperation. And replacing conflict with collaboration. And when countries come together and believe in this principle, this is the real solution. We are not lacking technology. We are not lacking the ability and we are not lacking water, by the way. We are lacking cooperation. I was talking to an expert from the Mediterranean, from Union for the Mediterranean, and he said a very wonderful thing. He said that you can see that in the north, the northern part of the Mediterranean, there’s no big water issues. In the southern part, there is a big water issue. But in the northern part, there is an energy issue which is not presented in the south. We have a lot of sun that can be can be used for the good and help the northern part of the Mediterranean and the northern part. They have the technologies, the desalination technologies. They have water. They are not going to export water, but they can export food. And this is how cooperation work? One country cannot do it all. We need to cooperate in order to use our resources in the best way.”

Knowing the specificity and needs of each region means having a historical approach. Not so different from the one proposed by Giulio Boccaletti in his water biography. Following the water, either from a scientific or a journalistic perspective, implies looking at the history of people and places.

Rehab Abd Almohsen: “ It is a big mistake from journalists to cover the cities without applying history in their thread. So let’s give an example of Venice or Alexandria. Those are very old cities that has many civilizations, many layers of civilizations. Ignoring this history and trying to discuss how Alexandria’s recent situation is troubling this city, how climate change is affecting the city, how sea level rise will affect the city is a big mistake. We cannot discuss this topic and the climate change recent events without taking into consideration the long history that this city has, how it was built, the problems that is that the city is having already not done by climate change, but done by human, by the way it was built by the way it was treated during history by the ups and downs that this city went through. This will be a big mistake. The same applies to Venice, I think, and all the Mediterranean countries, cities, you know, that there is a study that says that I think Istanbul, Venice, Alexandria are threatened by tsunami of all the Mediterranean. And they are going to be swallowed by the sea kind of kind of thing.

I’m Egyptian, but honestly, I ignored a lot about Alexandria and I discovered that Alexandria, especially Alexandria, was not well studied because of many things, because basically the old city is either under the water or under the ground. So while I was writing it, I discovered that the hardest part is to link signs, the recent situation, the recent scientific studies that have been made related to and its history. So not to mention land subsidy and how the city, the land and the city are going down. But also to mention that there is an old infrastructure beneath the land that is causing this land subsidy and this infrastructure was built by the Romans and the Greeks when they established Alexandria. When they built Alexandria.”

Giulio Boccaletti: “And so that process is really central to the creation of political institutions. After all, you know, you coordinate that collective agency through the expression of power.”

The expression of power around water is the fil rouge of Giulio’s book, spanning from the legacy of Rome to the American Republic and the British Empire till the modern era. And the key question is: how were the institutions that developed in antiquity transferred to modernity?

Giulio Boccaletti: “How did those ideas migrate? How did the idea of the republic make it into the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries? How was it modified, and how did it interact with water conditions at the time? For example, in northern Italy, in the city-states of northern Italy in order to then produce the ideas that were the basis of the sort of revolutions that led to the nation-state in the 17th, 18th and 19th century, as an example. Or, you know, the role of the empire, the British Empire or of the early American Republic in extracting the myths, the stories, the ideas that they read into the past applied to problems they had at the time. Mostly, again, about land management and choices, about the landscape and then how those then led to the 20th century. So the second part of the book, the thousand years are important because it translates the past to the future. Right they’re a story of how ideas evolved and international relations born. You know, the treaties of Westfalia and Munster, for example, are the foundation of modern international relations and they are treaties between sovereign nations recognising each other across rivers.

And so I’m trying to reveal again in this dialectic story how our relationship with water over time helped shape not just institutions but ideas.”

The ideas shaped by the human relationship with water directly fed what Giulio Boccaletti called the “hydraulic century”. This is the 20th Century, dominated by three main “ingredients”: the demographic explosion, the energy revolution and a greater desire for political emancipation. Combined, these elements led to more powerful institutions, giving birth to the modern states. Together with the illusion of controlling nature – and water.

Giulio Boccaletti: “One of the most important manifestations of the modern state is indeed the transformation of the landscape. It is the reason why you and I don’t wade a river on our way to work, and all of us get water from a tap that juts out of the wall instead of having to go down the street. All these things are expressions of the power to control the landscape that was exercised by the states over the 20th century. So I suppose that the third part is the, you know, the story of the Hydraulic Century, because it’s really the century in which, you know, through the state, humanity, particularly in rich countries, ends up exercising ultimate sovereignty over the landscape and ends up convincing itself that it has controlled nature. Of course that’s not true.

As people moved into the city and urbanised and more and more, there was this desire to kind of separate us from nature and it succeeded because, you know, the beginning of the 20th century, in 1900, we caught almost nothing that came down from the sky. There was very limited reservoir capacity. Storage capacity in the world. By the time we get to 1970, let’s say so less than a century later, we catch a fifth of anything that holds down on land on the planet. And so we’ve completely re-plumbed the planets in a matter of a generation to support industrialisation and development. Now that has had a cost. Again, like everything in this book, it wants to reveal this dialectic relationship and that too was a step in this dance that we took with water rights, because by hiding water behind all this infrastructure, by ensuring that on a daily basis we wouldn’t experience the variability in water, well then ended up happening is that we started believing that it had gone away, that it wasn’t hiding behind the dams and the reservoirs and the levees, but it actually was completely controlled. Except that then when it’s not right, because eventually then something happens, a dam fails or a levee isn’t big enough or, you know, a catastrophic event, as we’ve seen, you know, in Pakistan and in other places around the world, you know, exceeds the boundaries, the limits that we’ve set on water and shows us that we are still effectively subject to this very powerful force, the expression of the climate system on the landscape.”

This is something that will never end. According to Giulio Boccaletti, humanity will always be stuck in this relationship with water.

Giulio Boccaletti: “A dialectic relationship doesn’t end until one of the two people talking goes away and neither water nor we are going away. So we are stuck in this dialectic relationship. And I think that the first and most important thing is to recognise it is important because if you recognise this fact you also start thinking about, you know, things like risks differently. You think about the summer and the droughts that have hit the world in Europe certainly, or the floods that are hitting parts of Asia right now. We treat these things as unexpected catastrophes and we treat them as unexpected catastrophes because we expect everything to be controlled. But the reality is that the climate system is variable, and the expression of the climate system on the water, on the landscape, i.e. water is extremely variable and there’s an element of recognising that this is the case, right? And learning how to live with that risk so that you can also prioritise choices to control some of the worst risks.”

Giulio Boccaletti: “You know, the book essentially reveals that our choices about the landscape and about water are really choices about ourselves, about our liberties, about who gets to decide what, where, who gets to decide what you see when you look outside the window. That question is central to how we’re going to move forward in managing a different world environment.

Water is going to behave differently because of climate change. The distribution of water on the planet is going to be different. Where it is in time and space is going to be different. So some of the issues that even the developed world thought they had solved will in fact re-emerge as fundamental problems. And again, we’ve seen it in the summer, for example, the droughts that hit Southern Europe, the Mediterranean, Italy. The problem in Italy is not just that there is a climate shift or that the precipitation has changed. The problem is that the institutions and infrastructure that we developed over time and particularly over the 18th Century have failed. Right. And there’s a solution to that. You need new institutions and new types of infrastructure, but that requires money and power and resources. And so it requires politics.”

Politics. When you follow the water, this is the main take-home message across centuries: water is more of a political issue than a scientific or technological one. This is obvious when we think that, in any given place, people have to share this resource. And sharing a resource, particularly when it’s scarce, leads to discourse over power rights. It has to do with who has the power to overcome others and control that particular resource. Of course, then, there are more sophisticated arguments that we need to take into consideration when switching from the technological and scientific level to the political one, as Giulio Boccaletti reminds us.

Giulio Boccaletti: “I worked on water security in a number of countries for many years. And I realised after a while that while conversations about water tended to start in a technical and scientific place – how much water you need to grow something, or where would you put a dam, or how would you think about spending money on infrastructure? In the end, the conversation would always lead to identity and politics, to profound choices about the future of a particular society, whether it was working in Ethiopia or Jordan or Mexico or India or all these other places I worked in. And so I started realising that even though a lot of the conversation about water tends to be technical, its roots are deeply political. What I try to make is a more sophisticated argument about political institutions, that it’s political not just because it’s about power, but because it’s about the power of the state specifically. And the book is not deterministic. I’m not arguing that particular water conditions create particular forms of the state, but I do argue that’s the journey for, you know, the journey along which we formed state institutions and along which state institutions grew to become the most powerful institutions in human society. Right. I mean, remember that you know, today the modern state in a typical country controls somewhere between 30 and 40% of the economy of that nation. Right. So the institutional incredible power, well, that power was in part exercised as a sovereign power on the landscape in the form of the infrastructure that transformed it in service of industrialisation. So was this kind of interesting bargain that we did in the 20th century in particular, where, you know, we gave enormous power to the modern state in exchange for a controlled environment, in exchange for the transformation of the landscape like we had never seen before.

And because the solution to water problems is a profound modification of the landscape, it doesn’t really matter whether you’re talking about infrastructure or nature based solutions. It’s an exercise of sovereignty. You get to decide what you put where. Right. That’s a that’s an extreme power. And so I think that there are some lessons that have more to do with the behaviour of social systems rather than with the behaviour, the technical behaviour of the physical system that we should keep in mind as we look at what is going to happen in the future.”

You have listened to Foresight – Deep into the Future Planet, a podcast produced by the CMCC Euro-Mediterranean Centre on Climate Change and FACTA.

The concept, interviews and writing are by Elisabetta Tola and Giulia Bonelli.

The audio editing is by Lisa Lazzarato.

The Executive Producer at CMCC is Mauro Buonocore.

Foresight – Deep into the Future Planet, available on climateforesight.eu and wherever you listen to your podcasts.