Are you over 75? Are you sick or disabled? Unemployed or undereducated? Do you live alone or are you otherwise socially isolated? Do you lack access to green space? If you’ve answered yes to any of these questions, then you have an increased vulnerability to extreme heat.

These socio-economic conditions, coupled with rising temperatures and increasing rates of urbanization are leading to dire public health issues, including mortality. This has become blatantly clear and impossible to ignore over the past years. The 2003 European heat wave is perhaps one of the most remarkable examples of the risk of extreme heat; one of the first big events to bring public attention to the impacts of increasing temperatures due to climate change, especially on public health.

If you were living in Paris in the summer of 2003 you would have been largely left to your own devices and the support of your family to cope with the heat wave. After several consecutive days of unusually high temperatures, some emergency measures were taken, and an extreme heat plan was set in motion, including an increased number of nurses in emergency and medicine departments, an increased capacity of hospital wards, a decreased hospital stay for previously admitted patients, and cancellation of admissions for elective procedures. In the end, and despite the reactionary extreme heat plan, 15,000 excess deaths occurred over the month of August in France, with nearly 1,100 of those in Paris. The death toll in Europe topped 70,000.

Enlarge

SOURCE: Paris Resilience Strategy - http://www.100resilientcities.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Paris-Resilience-Strategy-English-PDF.pdf

We can observe from the losses suffered during the 2003 event that it is not sufficient to rely simply on ad hoc responses during extreme events, but that we should have a broader plan. Experts concur. According to Joacim Rocklöv, Professor in Epidemiology & Public Health at the Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine at Umeå University, “Adaptation to heat should probably not only be event based, e.g. heat wave or not, but need address situations of heat in general to be really effective. Thus, general interventions altering exposure such as urban design and green and blue factors are fundamentally important. Adaptation linked to extreme heat situations could probably benefit vastly from better mapping out of vulnerabilities better and target interventions to communities and people. More bottom up social engagement and reaching out to vulnerable groups from communities, such as those elderly living alone and with mental illnesses and family, would also be important.” This implies addressing the underlying causes of socio-economic vulnerabilities and giving more attention to urban design, rather than focusing only on relief from the heat and medical intervention once things go badly.

Adaptation linked to extreme heat situations could probably benefit vastly from better mapping out of vulnerabilities better and target interventions to communities and people

– Joacim Rocklöv, Umeå University

Prof. Rocklöv adds, “The European adaptation has been largely catalyzed by the 2003 heat wave. Today almost all European countries have heat warning systems, but the level of response actions connected to these warnings are highly diverse and so are the evidence-base of response effectiveness.”

In fact, in 2004, the City of Paris immediately released a four-level alert system following the motto “Heat can kill and we have learned the lessons.” Focused on responsibility, prevention, and solidarity, the system aims at boosting cooperation between emergency services, healthcare providers, and the police. It includes a new weather alert service, a registry of people at risk, and response guidelines for hospitals and voluntary aid workers. Although incomparable to the conditions of the 2003 heat wave, with the plan activated, the June 2017 heat wave is said to have caused only 580 additional deaths nationally.

A problem with Paris and all urban areas is that killer temperatures are reached faster than in less populated areas because the asphalt, brick, and concrete surfaces and dark roofs absorb heat during the day and radiate warmth at night. Cities even create heat, for example through the use of air conditions, which is a lifesaver for those who can afford it, but it makes the streets even hotter for those who cannot. This is the Urban Heat Island (UHI) Effect. UHIs, combined with increasing urbanization, are projected to increase the vulnerability, especially of the disadvantaged people, to heat-related impacts in the future.

Not only temperatures are rising; urban populations are growing too. The UN DESA projects 68% of the world’s population to live in cities by 2050. The threats of morbidity and mortality due to extreme heat are rising on multiple fronts. Adaptation and preparedness are not an option but a necessity.

Margaretha Breil, CMCC and EIEE Senior Researcher and expert on adaptation in cities, notes that in cities there is a need to look beyond emergency measures and to focus on longer term measures to reduce the UHI effect, such as increasing greenery and changing building regulations, echoing the sentiment of Prof. Rocklöv. However, she adds, we must remember that heat is not only an urban issue – people are dying in cities because of the UHI, but also in the countryside. So, taking measures can help to reduce the UHI, but it is still getting hotter everywhere.

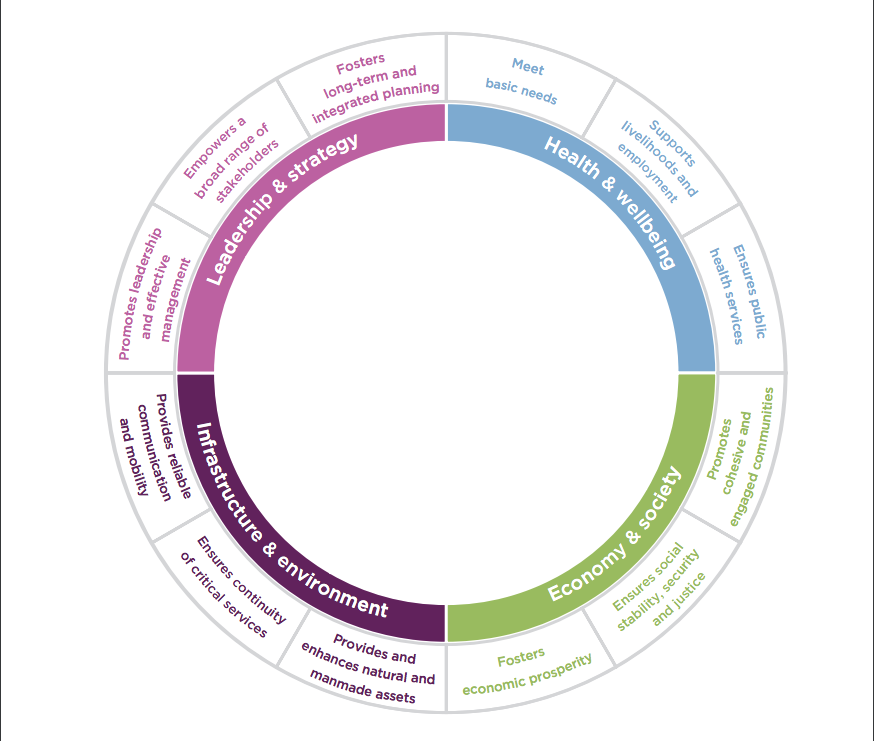

Along these lines, the City of Paris has released a resilience strategy in 2017, and now as of 2018, has a full climate action plan with goals of carbon neutrality and renewable energies. Climate change is expected to drive up temperatures in Paris by 2° to 4° in the coming decades, and therefore preparedness for heat and other risks is a must in the city and beyond.