Rising temperatures, changes in rainfall patterns, droughts, extreme events such as floods, storms, heat waves, increasing levels of carbon dioxide and sea level rise: the impacts of a warming planet are already becoming detectable in many parts of the world.

As the global population rises, urbanization increases, agriculture faces the challenges of meeting society’s growing food needs, addressing climate change impacts, while simultaneously reducing its environmental footprint.

What would happen if crop yields decline and become more variable as global temperatures increase? What would happen if the world’s largest crops producing and exporting countries face simultaneous crop shortfalls, with implications for global agricultural trade, prices and food security? Who would feel the effects? Consider for example maize, one of the world’s most grown and heavily traded cereal crops in international markets, having different uses such as livestock feed, biofuel and direct human consumption. In a warmer climate, maize yields will decrease and become more variable. Climate change will not only increase the risk of food shocks from world corn production but also that these crop failures will more frequently occur simultaneously. In the United States, Brazil, Argentina, and Ukraine, the top four maize-exporting countries which account for 87% of global maize exports, the probability that they have simultaneous production losses greater than 10% in any given year is presently virtually zero, but it increases to 7% under 2 °C warming and 86% under 4 °C warming. Simultaneous production shocks in these countries will have a significant consequence on global markets affecting especially the almost 800 million people living in extreme poverty. And it’s not the plot of a gloomy science fiction story; these are the results of a study recently published on PNAS exploring what will happen with unchecking climate change.

What are the best policies that we can have in place to respond to a drop in food production? Climate change represents a major pressure over a fragile system and so it will be essential to understand these key issues

– Michael J. Puma, Columbia University, New York, US.

International trade as a safety net

Michael J. Puma, Director of the Center for Climate Systems Research (Columbia University, New York, US) focused his studies on food security and in particular on the susceptibility of the global network of food trade to natural (e.g. weather extremes, droughts, volcanic eruptions) and manmade (e.g., wars, trade restrictions) disturbances. “There’s limited awareness of current vulnerabilities of the global food systems and trade to systemic disruptions, such as weather extremes, major crop diseases, epidemics and conflicts”, he says. “If there’s a major drop in food production – for whatever reason – how does the rest of the food system respond? What are the best policies that we can have in place to respond to that? Climate change represents a major pressure over a fragile system and so it will be essential to understanding these key issues.”

Enlarge

Imagine a developing country like Senegal, depending on imports for its staple food supplies: what would happen if there were a spike in global food prices? Or what if some of the major exporting countries, like US, Canada, Russia, Brazil, impose export restrictions because a major flood or drought disrupts their food production? What are the consequences for the rest of the world, and how do we minimize those impacts? All these questions, Puma says, are poorly understood and need urgent answers.

With climate change poised to alter significantly the ability of many world regions to produce food, it is expected that international trade in agricultural products will have an increasingly important contribution to feeding the planet and responding to climate-related hunger flare-ups, according to major studies such as the recent FAO report The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets, 2018.

“International trade has the potential to stabilize markets and reallocate food from surplus to deficit regions, helping countries to adapt to climate change while contributing to food security”, Puma explains. For example, international trade helped prevent a major food security challenge during Europe’s heat wave in 2003, while its absence was a major reason why severe flooding initiated famine conditions in North Korea during the 1990s. Enhanced local and regional resilience to food-supply disruptions as a result of international food trade is therefore invaluable.

“At the same time”, Puma adds, “we must be aware of the fact that global trade can introduce systemic vulnerabilities to countries’ food supply if you don’t have the proper policies in place, for example, if a country over-relies upon imports for its staple food or is very sensitive to global food prices.” Dr Puma and his research team are designing computer models to better understand self-propagating trade disruptions: the tendency of countries to protect their domestic markets using trade restrictions; such restrictions can propagate because countries tend to flip between exporting and non-exporting states depending on the trade status of their neighbours.

Enhancing the resilience of the food system

What are therefore our options to mitigate global systemic risks and enhance the resilience of the global food system?

In his research, Dr Puma underlines some key strategies, such as creating “redundancy” and diversity within the food system. In this context, redundancy means that, if food production or trade of certain commodities is interrupted, other nodes of the food system can make up for the losses. This is challenging for the tighter relationship between agricultural supply and demand – likely to be exacerbated in the future due to climate change, a shift towards wealthy diets, growth in population, biofuels and depletion of water resources. Some solutions involve diet diversification or increases in domestic production in countries that depend heavily on imports or in which a specific crop represents a large percentage of the nation’s diet.

Fostering diversity in the global food system is equally challenging because, over the past 50 years, we have seen a narrowing in diversity in crops. On the contrary, there is a critical need to continue to support and expand breeding and cultivation of varieties that have diverse genetic backgrounds.

Another essential issue to enhance the resilience of the food system requires that countries consider balancing food self-sufficiency and import dependency, that is designing the food system to that is not vulnerable to fluctuations in food supply and demand. Other important steps include new investments in food buffer stocks, increased domestic yield improvements, and protection of agriculturally productive lands.

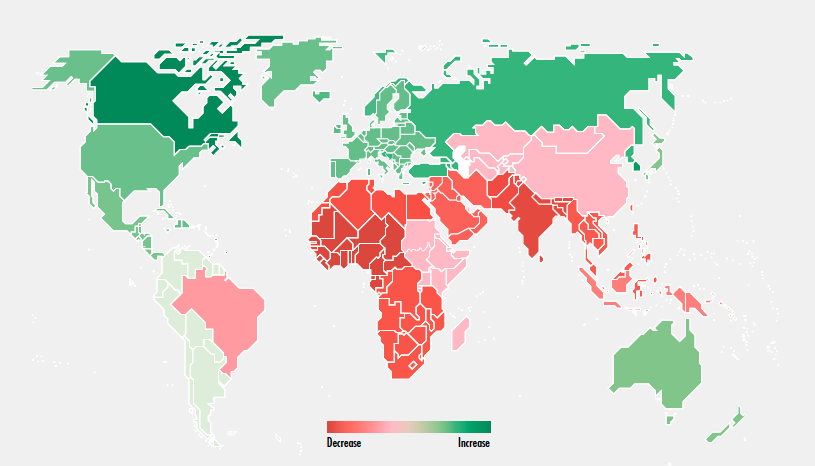

Enlarge

NOTE: The final boundary between the Republic of the Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. Final status of the Abyei area has not yet been determined.

SOURCE: Based on data provided by Wageningen Economic Research. 2018. Climate Change and Global Market Integration: Implications for global economic activities, agricultural commodities and food security. SOCO 2018 Background Paper, Rome, FAO.

“A key issue to be discussed in the future”, Puma says, “will be the emerging scenery of large-scale intensive farming systems. These farming systems based on monocultures are a reason for concern because they introduce vulnerabilities: they use in fact homogeneous crop varieties more vulnerable to climate change impacts or other disruptions (e.g.: if you plant corn over a huge area and a crop disease comes along, you have the potential to lose the entire crop). We have to rethink ways in which we produce our food and reverse this trend of large monocultures.”

The burden of climate change on agriculture

National agricultural and trade policies may need to be readjusted to help transform the global marketplace into a pillar of food security and a tool for climate change adaptation. This is because climate change will affect global agriculture unevenly, improving production conditions in some places while negatively affecting others.

Food production in countries in low latitudes – many already suffering from poverty, food insecurity and malnutrition – will be hardest hit, an FAO report notes. Regions with temperate climates, on the other hand, could see positive impacts as warmer weather lifts agricultural output.

Climate change is expected to result in declines in agricultural production in large parts of Africa, the Middle East and South and Southeast Asia. These declines are projected to be more pronounced in West Africa and India, where production could decrease almost 3 and 2.6 percent respectively due to climate change impacts.

In higher latitude regions, higher temperatures are projected to result in increases in agricultural production, as for example in Canada (2.5 percent) and the Russian Federation (1 percent).

CMCC researcher Arianna Di Paola, an agricultural expert in the IAFES Division, found out both opportunities and risks for Russian agriculture as a consequence of climate change. “We explore the effects of global warming on Russian agriculture while focusing in particular on the expansion of wheat thermal suitability of Russia in response to climate change; Russia is currently one of the world’s leading wheat producers and exporters, and changes in its agricultural production can have implications for the world commercial agriculture and food security. We noticed that wheat and more in general Russian agriculture could most benefit from the global warming in the north-western regions (Ural, Siberia) and the Far East, even though the current most productive areas in the south of Russia will likely experience a decline in land suitability for more frequent stressful heat and droughts events.”

Climate change is altering the spatial distribution of crops. But, even more importantly, climate change enables invasive species, weeds, pests and fungi to expand their range and numbers. “The majority of the investments in agriculture are for pest and disease management”, Di Paola explains. “If climate change will make the spread of crop pests and diseases easier, renewed efforts to monitor and manage them will be critical in controlling this growing threat to global food security”.

To cope with this problem there are different strategies, for example, we could use the more resistant landraces, contrary to the current trend of using monocultures of modern cultivar coupled with a large number of pesticides returning higher yield yet severe implications for the environment and consumers’ health.

In a changing climate, we should rethink our food choices: what we decide to eat has different impacts on the environment, economy, health. If people from countries where meat consumption is high and intensive reduce meat consumption by renouncing for example an hamburger per month, we could recover from several impacts, such as land consumption, water use, and GHG emissions.

– Arianna Di Paola, CMCC Foundation.

New agricultural practices, such as those at the base of agro-ecology, aim at improving the resilience of the food systems (and not at increasing yields) mainly by increasing the genetic diversity in the field (e.g. using polyculture), looking for ancient, traditional, more resistant and well-adapted crop varieties, and the use of natural enemies in place of insecticides. Other practices, such as those at the base of climate-smart agriculture, aim at sustainably increasing agricultural productivity and incomes while improving natural resources management.

At the same time, agriculture has a significant environmental footprint and directly contributes to climate change. These impacts include those caused by expansion of croplands and pastures into new areas (replacing natural ecosystems) and those caused by intensification, when land is managed to be more productive, often through the massive use of irrigation, fertilizers, plant protection products (fungicides, insecticides, etc) and mechanization.

From the Fifties, industrialized countries intensified the efficiency of animal-source food production shifting from extensive, grazing, small-scale, subsistence animal farming systems towards intensive, large-scale, specialized production units known as Intensive Animal Farming Systems (IAFs). Even if IAFs are mostly located in developed, large and quickly emerging countries, they represent a global food issue accounting for more than 40% of the global animal-source food, being a relevant source of greenhouse emissions and sharing a significant portion of the global crop production to feed livestock.

“Currently, a large portion of crop and food production is funnelled into animal feed (in particular of animals from IAFs) or biofuels despite widespread hunger and undernutrition”, Di Paola explains. “As shown in our study, plant-sourced proteins demand less natural resources, release fewer greenhouse gases, help the natural regeneration of the soil and, from a medical point of view, appear to be healthier. In a changing climate, we should rethink our food choices: what we decide to eat has different impacts on the environment, economy, health. If people from countries where meat consumption is high and intensive animal farming systems account for a great share of animal food production, reduce meat consumption by renouncing, for example, a hamburger per month, we could recover from several impacts, such as land consumption, water use, and GHG emissions. While the transition of our energy/production systems may require enormous investments and take a long time, people, in turn, can start changing their food choices today and with little investment.”

content