“Polluter pays” is an international environmental law and policy principle widely rooted in the legal realm, adopted by the OECD in 1972 and one of the key principles underlying the European Union’s environmental policy. It can be explained with an easy statement: those responsible for pollution should bear the costs that would otherwise weigh on society. It may sound easy, but it comes with many implications for human activities, including technological innovation and deep evolutions in the actual economic system.

Applying the “polluter pays” principle to CO2 – which is considered a form of pollution as it is the main greenhouse gas responsible for climate change – means giving a price to carbon: an economic signal that disincentivizes emitters from burning fossil fuels and incentivizes them to find less carbon-intensive solutions for their activities.

“When someone looks at the problem of climate change, a large part of which is due to carbon dioxide emissions, the only approach that one can credibly assert is going to be environmentally effective and economically efficient, is to price carbon emissions,” says Robert N. Stavins, the A.J. Meyer Professor of Energy & Economic Development, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

Carbon pricing ties the external costs of greenhouse gas emissions to their origin. Carbon pricing can be implemented through two main policy instruments. A carbon tax, which is a mechanism that establishes a predefined carbon price which is then applied to the units of greenhouse gas emitted, usually expressed as a value per ton of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2-eq). The second instrument is Emissions Trading, also known as the carbon market, where a given number of emissions allowances – each of which usually gives the holder the right to emit one ton of CO2-eq – are assigned and can be traded among emitters. In this case, the market implicitly sets a non-fixed price to carbon emissions.

What is a carbon market

The objective of trading emissions allowances on a market is to reduce the overall cost associated with GHG emissions reductions. This is made possible by putting in place an emissions trading system. Usually, it takes the form of a cap-and-trade system which limits the total amount of emissions that can be released in the atmosphere within a system by setting a “cap” to them, which is tightened over time in order to meet climate change mitigation goals. A defined number of carbon credits are assigned or auctioned to emitters, who can exchange such allowances through the carbon market.

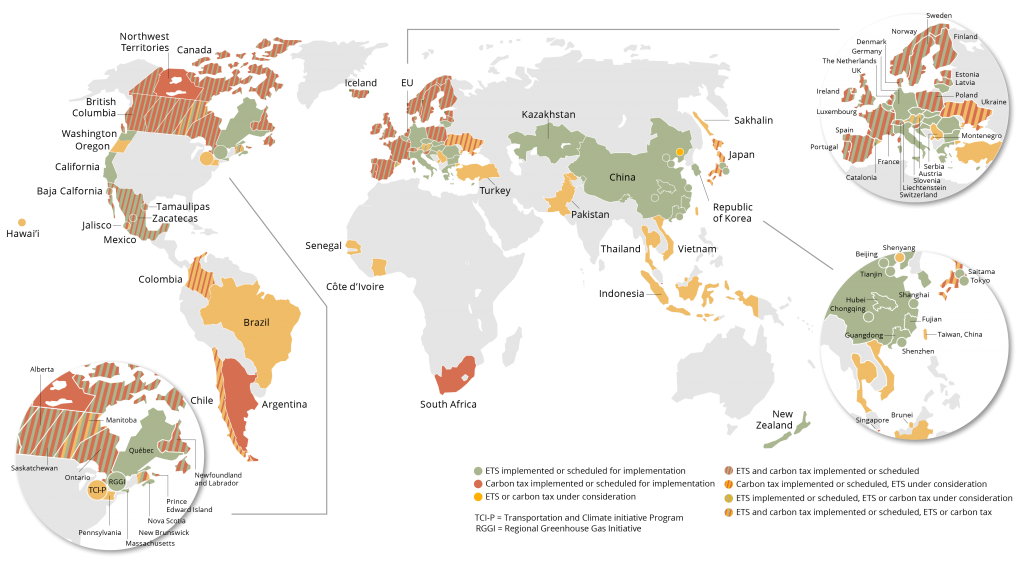

Carbon market mechanisms can be established at an international, national, or sub-national level, depending on the geographical coverage of the emissions.

In an emissions trading system, regulated entities can either:

- reduce their emissions – for example, by investing in innovation and low carbon technologies or removing GHG from the atmosphere – and sell the surplus allowances that result from their investment on the market;

- buy allowances on the market, if this is more convenient than reducing their own emissions.

Their choice would therefore depend on the relative costs of the two options: as a result, emissions will be reduced most by those emitters who have lower emissions abatement costs, thus resulting in a cost-effective policy at a general level. Indeed, emissions will be reduced in areas where savings can be achieved most cost-effectively.

“The genius of cap-and-trade systems, when they’re done properly, is that they both use a stick and a carrot,” says Vijay V. Vaitheeswaran, Global energy & climate innovation editor at The Economist. “That gives them an incentive to innovate, to get cleaner and cleaner: it provides that carrot for innovation.”

Before being applied to CO2, a successful experience with a large cap-and-trade system to abate pollutants was implemented in the US with the sulphur dioxide (SO2) cap-and-trade programme in the 1990s.

From theory to practice

A global carbon market would play a key role in the efforts to reduce GHG emissions globally and meet the Paris Agreement goals in a cost-effective way. At the international level, carbon trading was first set out in Article 17 of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, according to which countries with emission allowances to spare could sell them to other countries that could use them to meet a part of their emissions reduction targets under the agreement.

Besides International Emission Trading, the Kyoto Protocol set two other market-based mechanisms (Clean Development Mechanism – CDM) and Joint Implementation (JI). The objective of these flexibility mechanisms was to abate emissions where the costs were lower and, at the same time, transfer know-how and technology to developing countries.

In the Post-Kyoto era, Article 6 of the Paris Agreement regulates how countries cooperate – from bilateral trade to international carbon markets – to enhance mitigation outcomes and support adaptation, and establishes a framework for common robust accounting rules.

“The provisions included in the Paris Agreement’s Article 6 build on the experience of Kyoto’s mechanisms to create stronger and more efficient tools able to ensure transparency and environmental integrity in international climate cooperation,” says Marinella Davide, Marie Skłodowska-Curie research fellow at Ca’Foscari University and affiliated researcher at the CMCC.

“Many emissions trading schemes have been launched in the past years and the amount of emissions covered by a carbon price is growing substantially. The Paris Agreement offers a framework for countries to link them and to access a wider range of abatement opportunities at a lower cost,” she continues.

As they wait for the implementation of a global carbon market, national or sub-national emissions trading schemes are developing worldwide. The European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU-ETS) was the largest example until 2021, when China launched its national emissions trading system. Other national or subnational systems already operating or under development include Canada, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, Switzerland and the United States.

The EU Emissions Trading Scheme

The EU-ETS, established in 2005 to meet the Kyoto targets, is the world’s first major carbon market, covering the EU’s highly polluting sectors, from electricity and heat generation to energy-intensive industry sectors (e.g. oil refineries and steel production) and commercial aviation. The system has contributed to a cost-effective reduction of emissions covered by the EU-ETS of over 40% since its birth, not without facing obstacles in its path, such as the drop in carbon prices due to a surplus of allowances linked to the economic crisis and addressed with the introduction of a Market Stability Reserve in 2019.

A complete revision of the EU-ETS, which is a cornerstone of the European climate policy, is in its final negotiation phase as part of the broader “Fit for 55” package. The reform, criticised for its lacking ambition, extends the scheme to emissions released by the maritime sector, establishes a separate emissions trading system for buildings and road transport and introduces new measures to correct the biases observed in these years of experience in emissions trading. Among them, the carbon leakage, a delocalization of polluting activities towards countries with less ambitious environmental regulations, which in the new reform is corrected by a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.

“The European Union’s experience played a crucial role in expanding knowledge about the emission trading scheme as well as in improving the global confidence in carbon markets as a key and flexible climate policy tool to achieve emissions reductions. This paved the way for new initiatives to be implemented at different levels of governance,” explains Marinella Davide.

“Recent national and international developments also helped create larger and more sophisticated international carbon markets that will likely increase in complexity as the number of actors and geographic coverage expand. However, this will also allow for broader opportunities in terms of global investment, technology deployment and abatement solutions,” she concludes.