A 30-year period of observation is what is needed to determine the average weather conditions that define the “climate” of a given place, serving as a starting point to identify and describe a changing climate. From his thirty-year career at BBC News, science correspondent Jonathan Amos helps bridge the gap between the worlds of science and media communication, having witnessed the evolution of both climate sciences and the transformative revolution of journalism, from the days of print to the modern era of online publications and the coming influence of artificial intelligence.

Reflecting on your tenure as a science correspondent with the BBC since 1994, how has climate change reporting evolved?

Over the thirty years of my career, I’ve witnessed remarkable changes in the scientific understanding of climate change. I have seen scientists become more sure about what is happening to our climate over that time, about the physical processes at play.

Initially, there were substantial uncertainties surrounding the magnitude and direction of the changes that were occurring in the climate. Even if in the 1990s there was already a good sense that such changes were human-induced, the extent of this influence remained uncertain. With the release of the IPCC’s Third Assessment Report in 2001, the human impact on climate started to become really robust.

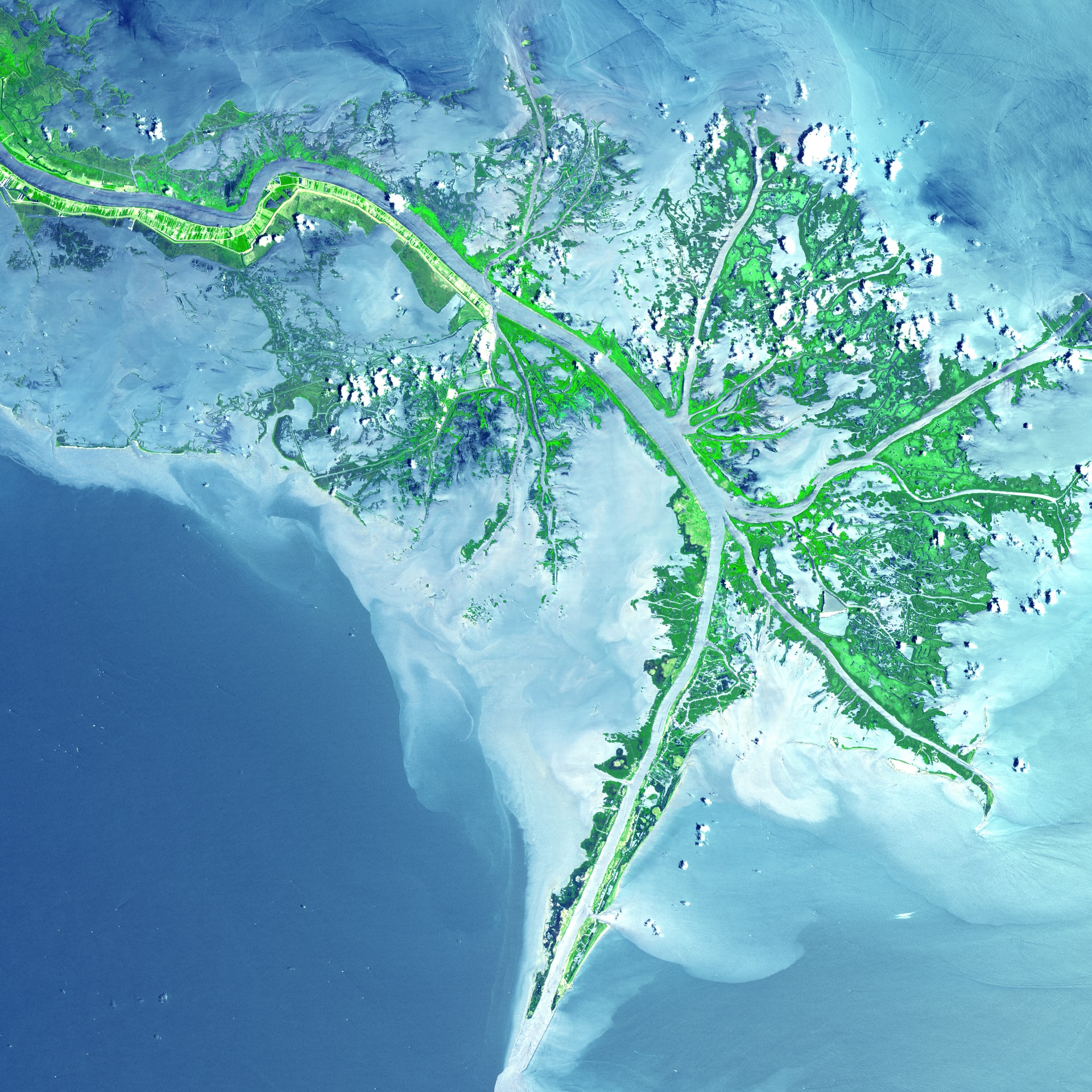

When I first reported on climate change, and particularly on the polar areas, there was considerable uncertainty, especially concerning Antarctica’s mass balance. Over time, advancements in satellite missions like IceSat, CryoSat, and Envisat have unequivocally shown the loss of mass in Antarctica and Greenland over the past two decades. Now, the focus has shifted from debating whether the ice is melting to understanding the rate and magnitude of this change.

Take sea-level rise as another example: from the very first TOPEX/Poseidon satellite mission to the recent Sentinel 6 mission, we’ve observed a steady acceleration from 2 millimetres per year to potentially up to 5 millimetres per year. Understanding its sources – from melting ice sheets and glaciers to oceanic thermal expansion and groundwater storage changes – has grown clearer.

Readers seem to increasingly select news that aligns with their preferences and tolerance for negative information. How does this affect climate change reporting?

In recent years, there has been a growing aversion to negative news, not surprisingly: there is a war in Europe, there is a cost of living crisis, and everybody was touched by COVID in some way.

Through our statistics at the BBC, we observed that people are trying to avoid such exposure, and this tendency reflects all types of stories, including climate change stories, which often entail distressing reports about melting ice sheets, rising seas, and extreme weather.

But what we have found is that people respond to what we call “solutions journalism”. They want to know what the potential solutions are, and we get good engagement for those types of stories. People want to understand alternative energy options and individual actions that can drive positive change. This is very clear: if you can present people with climate solutions, they become really engaged.

As a journalist, how do you decide what you want to cover, especially when it comes to climate change’s ability to meet news criteria?

Every news story, including climate-related ones, undergoes scrutiny based on various criteria: importance, magnitude, exclusivity, relevance, timeliness, human interest, controversy, counter intuitiveness – people think something, but actually it is not like that – and zeitgeist. The latter is about trending topics, which are topics that everybody is talking about at that moment, and you know people are very interested and keen to learn more about them. We measure any piece of information against these criteria, and if they reach a certain bar then it is something that is worth reporting.

In particular, we evaluate new scientific studies based on their novelty. Incremental advancements – i.e. small advances on what we knew before – might not warrant coverage, but groundbreaking discoveries or new data-driven news stories do.

Given the extensive advancements in climate science, is it becoming harder to meet these criteria?

Admittedly, it does get harder over time to surprise audiences about what is happening to the climate. However, climate change remains a trending topic, constantly evolving with new findings, and people are still keen to hear about what is occurring. While some low-hanging fruits have been picked, there’s still much to uncover about our changing climate.

How can climate change remain a trending topic in the coming years?

To sustain interest, storytelling approaches may require modification, emphasising solutions, as we are already doing. While not always dominating headlines, discussions surrounding climate change pervade various spheres. As people start viewing all earth sciences through the lens of climate change, it retains its relevance and significance.

How has the BBC’s internal guidance on climate change reporting and “false balance”, issued in 2018, impacted your work as a science reporter?

The BBC’s guidance targeted specific programming issues, distinct from the work of science reporters. While some BBC coverage faced problems that prompted this guidance, it was directed at particular programme types and did not reflect the activities of science reporters, who did not engage in false balance.

When uncertainties arise in research, my approach isn’t to present opposing viewpoints merely for the sake of balance. My response to the grey area is not to find somebody who denies climate change. Instead, I seek expert insights to navigate complexities.

There are different programme formats, such as radio and TV programmes, where people have debates. And the mistake that led to that editorial policy update was the idea that these programmes needed to balance opposing viewpoints on climate change, primarily for the sake of argument rather than delving into the issue itself. This is known as “false balance”.

However, the debates were focusing on the wrong aspects: the broad tenets of climate science are unarguable now. Legitimate debates can revolve around how we tackle this challenge, the policies to pursue, the balance of renewable energies needed, the transition from reliance on gas and coal, and the rapid deployment of electric cars in Europe. These are policy matters that merit debate, but the discussion about the fundamental physical basis of climate change is no longer up for debate. So, by all means, have the policy debate. But don’t ask me to sit there and have somebody saying climate change is real and somebody saying it’s not real. We’re past that.

How did you establish a network of climate science experts and how do you report on their research?

Building this network took time and effort. When I was a young reporter starting out for the very first time, I struggled to find stories worth reporting on. After a period of time, I started to build the network up, and now I have so many offers of story ideas that I have to be very selective about what I write. I like to ask scientists for two crucial elements: time and pictures. An advance notice to prepare news reports before their research findings are published is crucial, because a scientific paper is old the moment that the curtain is lifted. And visual content is essential to complement the story, as visuals often enhance reader engagement.

Jonathan Amos

Jonathan Amos has been a science reporter with the BBC since 1994. He was part of the team that set up the BBC News website in 1997. His online reporting focuses on the Earth sciences, with a particular interest in the changes taking place in polar regions. Jonathan is also known for his coverage of European space activities.