Interview by Annalisa Gratteri

Corals are fascinating creatures, with gorgeous colours and a unique ability to turn dissolved salts in seawater to stone, gradually building mighty reefs that can even be admired from space. A magical feat which they perform by relying on a mutually beneficial partnership with tiny algae, nestled inside their cells, receiving sugar – energy – in exchange for protection and nutrients. A beautiful balance whose intricacies are revealed in the many stories and metaphors used by Juli Berwald.

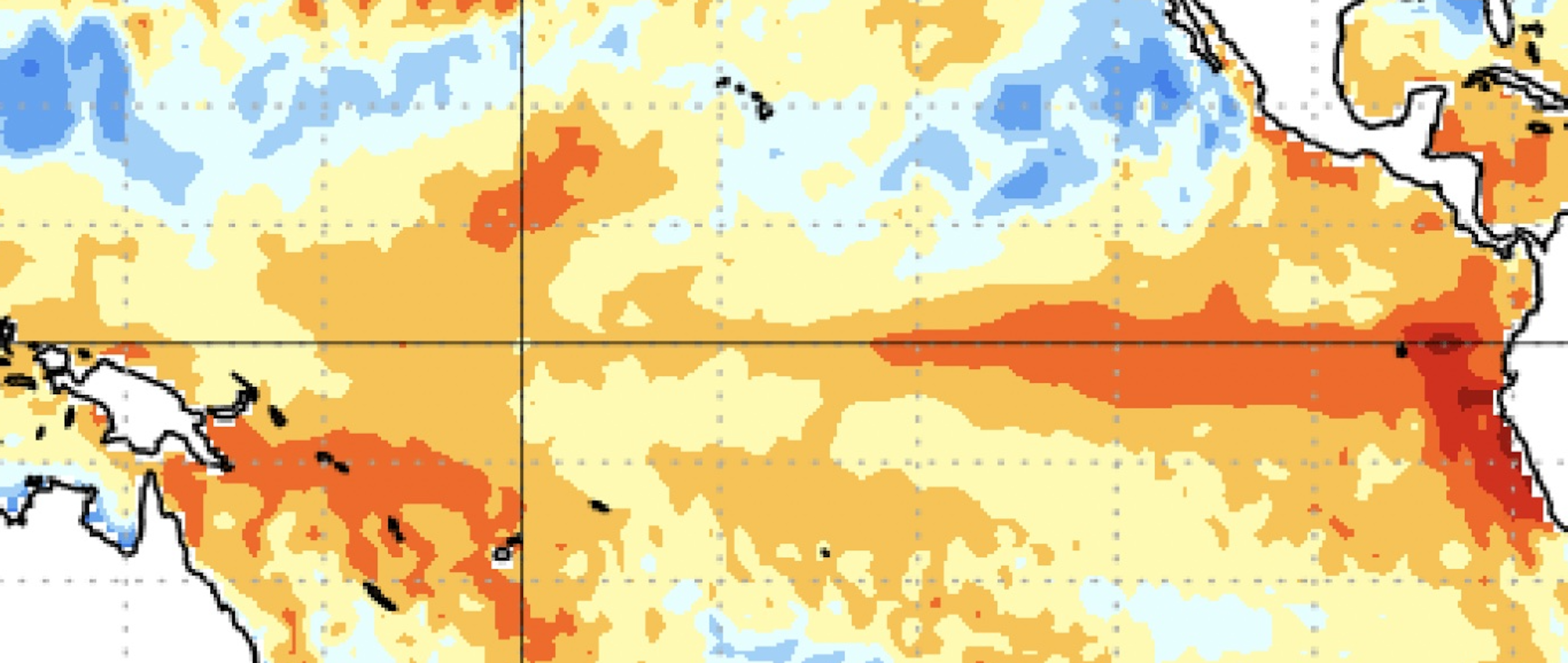

In fact, biological complexity and partnership is part of what makes corals resilient in the face of climate change, water pollution and illegal fishing. At the same time climate change is damaging to corals because increases in water temperature tear apart the powerful partnership between coral and algae, a process known as bleaching.

The hardship coral reefs are facing, from the Caribbean to Indonesia, Australia and beyond, are a threat to both overall marine ecosystems and the people whose livelihoods depend on them. This has led a global community of devoted scientists and activists to explore ingenious ways to protect corals from rising temperatures and bleaching, and hence restore them to their previous richness and vibrancy. Successful projects, such as the Mars Reef Stars in Sulawesi, give us hope and optimism.

While following Berwald around the world, across her many encounters with scientists and local communities, we also get to know her story and that of her family, their struggle with her daughter’s mental illness, and her own fragilities, resilience and hope.

How are you able to bring science and emotions together in your book?

When I realised I wanted to move from being a science writer for magazines and textbooks to writing a book I was still quite intimidated by the idea. I would read science books and think that I would never be able to write something like that. However, I soon realised that the key was to write with my own voice and try to engage readers with my story.

Lots of science based books are written by men and their voice is not my voice. When I changed the inflection it was as if I had found freedom, it changed everything for me, I started putting my own stories into everything I was writing and it felt so good. Although this was scary at times, it was the authentic thing for me to do.

The battle to save coral reefs is a small part of a bigger fight against climate change, an issue which many people feel dispirited and powerless against. Do you think that stories like the ones you tell in your book have the power to give people hope?

I’ve been talking to a lot of young people since the book came out and they often convey feelings of despair. They are in a crisis mode. For me, being in crisis mode doesn’t work well, I need hope. That’s not to say that I don’t see the real challenge that coral reefs are facing. They are facing an existential threat. However, as I look around the world I do see examples of resilience.

Even when there is a mass bleaching event there are always survivors. It’s not all over yet and to say that there is no hope for coral reefs is unfair. Even though they occur in less than 1% of the ocean, that is still huge. The Great Barrier Reef alone is the size of Italy, and even if half of it dies that still leaves a massive area of surviving reef. There is real hope, which has to be balanced with the fact that there are critical threats.

The latest World Ocean Day revealed the UN’s focus on having at least 30% of oceans protected by 2030. Could you tell us more about the current ideas to try and stop ocean overexploitation?

The idea of 30 by 30 is important, as marine protected areas are probably one of the best tools we have to protect the marine environment at our disposal. These areas offer a wide range of protections, not all of which are equally beneficial. Some, like simply being anchor free but still open to fishing, might not do much to protect habitat.

That said, no-take marine protected areas are the most effective. In these zones, no fishing whatsoever is allowed and there is evidence this protects the marine environment and leads to an increase in fish populations outside of the protected areas as well. One of the key ingredients in establishing marine protected areas is to involve local people in determining where the zones should be, what rules should be implemented and also in taking care of the areas themselves.

There are also some really interesting ideas and financial tools that are being discussed and implemented where debt can be traded for marine protection. In the Seychelles, they have protected 30% of their marine coastline using this scheme, an example that I discuss in my book.

Should storytelling that looks at the relationship between humans and nature from a scientific point of view also include descriptions of humans as part of the solution?

Certainly. One example is the traditional marine tenure system called Sasi and put in place by native people in the Pacific Ocean. The chiefs would put special wooden markers on the beach and people would decorate them with flowers, which meant they were not fishing or hunting for turtle eggs or for example.

There is a real understanding that the ocean needs time to recover from what we impose on it. And of course industrial and illegal fishing do not follow these rules. I agree that storytelling is a really important way to, at the very least, expose the gap between traditional knowledge and industry. We should be working towards finding these connections.

You give figures about the economic value of reefs in terms of coast protection, fish nurseries and even the cost of restoring coral reefs. Do you think that stressing the monetary value of ecosystem services helps raise awareness in people?

It is always problematic when you try to put a number on something like a coral reef, which is a true treasure of our planet. However, we live in a capitalist world and I think it would be negligent to not try and put some numbers in place to get people’s attention.

The value of the world’s coral reefs is between two and ten trillion dollars a year in ecosystem services, such as fish nurseries or coastal protection. Although they occur in only 1% of all oceans, a quarter of all marine species depend on these reefs at some point in their lives. Corals have a disproportionate impact on life in the sea.

The value of these reefs is immense, yet the amount of money we dedicate to ensuring their wellbeing is very small. I struggled with putting these numbers in the book, but I think we need to face them: we need to reveal how our oceans are being undervalued.

What coral restoration projects do you think are most effective and promising in terms of proposing concrete solutions?

The most surprising – and successful – was implemented by the Mars candy bar company, Mars Incorporated, in Sulawesi, Indonesia. This is an area of massive coral diversity known as the Coral Triangle, found between Indonesia, the Philippines and Papua New Guinea, which has been affected by mass bleaching and even more pressingly blast fishing, whereby fishermen use explosives to catch fish.

Blast fishing is driven by poverty because it’s cheaper for the fishermen to catch fish this way. However, the practice turns the reef to rubble, which prevents coral from re-establish itself. In answer to this Mars Incorporated developed structures that stabilise the reef called Reef Stars, as well as paying local fishermen to assemble corals on the Reef Stars.

They also play sounds of a healthy reef to attract fish. It is very important to get herbivores to come back to the reefs that are under restoration as they eat large algae which would otherwise override the coral.

Villagers have really bought into the project and they are seeing fish increasing in numbers around the restored areas. If you visit restored sections, even ones that are only three years old, it’s absolutely incredible: the corals have covered every inch of the structures, hiding the old damage. I saw turtles, sharks and all kinds of fish. It’s a vibrant living place again. A glimmer of hope that restoration is possible.

Considering the genetics, biology and evolutionary story of corals will they be able to adapt to a changing climate?

The magical part of corals is that they are animals, just like we are. However, the bulk of their nutrition comes from a collaborative partnership with an algae. The algae lives in the corals’ tissue like a tattoo, it photosynthesises like all green plants do, making sugar, 90% of which goes to the coral.

The problem is that when the ocean warms by a degree or two, for a month or even just two weeks, the algae leave the coral and take with them all the colour. A coral reef that has undergone bleaching looks white because it is simply the remaining tissue or skeleton. But corals are bad asses, they are tough and the symbiosis can be re-established if the water cools down again.

Now we are seeing adaptation on the reef. A new algae can colonise the coral and this algae can actually withstand water temperatures which are a degree or even a degree and half warmer than before. However, it is a more selfish algae which feeds the coral only about 60% of the sugar it produces.

We are starting to see this kind of shift and so maybe there is some hope. The scientists who discovered this call it “a nugget of hope”.

Your use of metaphors to explain intricate biology comes to life when you characterise the symbiosis between a coral and an algae as an engaging story of two characters. How important is it to use storytelling to convey complex scientific ideas that transport the reader?

I love this approach. I really take great joy in finding a good metaphor and think of them as an advertising campaign for the scientific process in question. What I love to do is to start by trying to understand the scientific process really, really well. I then clear it from my mind and let the metaphor come to me, crystalizing the process in a simple and clear way.

Juli Berwald received her PhD in Ocean Science from the University of Southern California. Author of Spineless and Life on the rocks, as well as a science textbook writer and editor, she also writes for a number of publications including The New York Times, Nature, National Geographic, and Texas Monthly.

Juli Berwald received her PhD in Ocean Science from the University of Southern California. Author of Spineless and Life on the rocks, as well as a science textbook writer and editor, she also writes for a number of publications including The New York Times, Nature, National Geographic, and Texas Monthly.