Climate change can be observed, studied, described, predicted… and captured. Increasingly, photography can help document the causes and effects of a warming planet, whilst also showing what solutions we have at our disposal and how science is driving change.

“Photography has a huge part to play in communicating the climate change message,” says environmental photographer Ashley Cooper, whose snapshots from around the world provide a powerful depiction of the impact of global warming on people, places, and wildlife. Visual stories that make up the world’s single largest collection of climate change imagery on climate change, and are used in books, newspapers, and magazines around the world.

Behind every picture there is a wealth of reflection and study of the best way to reach and touch each viewer, connecting the spheres of science, art and climate change communication. Not to mention a fair amount of courage needed to embark on expeditions to the farthest corners of the earth.

In your work, you document the impacts of climate change. But you also showcase global solutions to the climate crisis. What narratives are most effective when talking about climate change today, and how can photography propell urgent action?

I think photography has a huge part to play in communicating the climate change message. Most people today are pretty good at understanding the causes of climate change. What they don’t necessarily have as much understanding of is the multifarious impacts that it is having around the planet: many different environments and species are being impacted by climate change in a lot of different ways.

Moreover, there is no point just saying to people “Look there is a big problem” if nobody knows how to deal with it, or how to implement the right solutions and decisions to try and reduce their own carbon footprint. I think there is a lot of power in communicating the solutions to people through imagery.

So, by documenting all the various renewable energy solutions that are available at the moment, we can send the powerful message to people that there is something we can do about it. My house uses very little electricity from the grid, because I generate most of my electricity and hot water myself. These technologies are getting cheaper and cheaper, they are available and affordable to a lot of people. But people need to be shown the available solutions in order for them to make decisions that contribute to the process of trying to prevent further climate change.

There is often a dichotomy between, on the one hand, the apocalyptic vision of a world that is plagued by extreme events and, on the other hand, the science that provides information on different scenarios and different opportunities. How can photography connect to climate science and foster coherent and rigorous communication?

Whenever I went on a photoshoot around the world I connected with scientists working on climate change in the country that I was visiting. A large part of my work was about documenting the important work of scientists. It is only through science that we have the knowledge about what is happening, why it is happening and what we can do about it, and I think photography is a powerful tool to show the important work scientists are doing around climate change. It is very important that not just photography, but a lot of other art forms as well, engage with the climate sciences so that we can deliver coherent messages to the general public.

At the same time, in the twenty years that I have been documenting climate change, I have observed that scientists have come a long way from just doing the science and now also communicate a lot more effectively. Now there are more scientists who are prepared to stick their heads out, engage with the media, and talk about how their science is demonstrating the dire need for very urgent action on climate change.

Of the photos you have taken throughout your professional career as an environmental photographer which has had the strongest impact on you?

Of all the hundreds of thousands of images of climate change that I’ve taken, the dead male polar bear (Ursus maritimus) I photographed in 2013 on Svalbard is probably the most famous image. It was the first time that a polar bear, in all likelihood, had been found to have died as a result of climate change.

When we found the polar bear, it was just a pack of skin and bones and it looked like it had starved to death. It had been collared by the Norwegian Polar Institute and spent all its life on Southern Svalbard, doing what polar bears do, which is basically just sitting around, doing nothing during the summer months, fasting, relying on the fat reserve and waiting for the sea ice to form. When the sea ice forms they hunt seals, which is their main prey, but they can only hunt seals on the sea ice.

The western fjords of Svalbard, which normally freeze in winter, remained ice free all season during the winter of 2012/13, one of the worst on record for sea ice around the island archipelago. The Norwegian Polar Institute tracked the polar bear walking over 400 miles due north, presumably in an attempt to find some sea ice. With no sea ice, there was no habitat for the polar bear to hunt for food. For this reason, we can say that the most likely scenario was that the polar bear starved to death due to global warming.

The Guardian used this photo as their lead story on the front page, after which many others all around the world followed suit, including BBC News, Al Jazeera, NBC News.

What about the communication ecosystem around you? Are there any initiatives that have impressed and inspired you in the field of climate communication?

There are a few people working on similar projects to mine. One in particular is James Balog, in the United States. In the long-term photography program called Extreme Ice Survey, he has been putting timelapse cameras on the side of glaciers all around the world and documenting the rate at which those glaciers are retreating. That strikes me as a good way of spreading the message of how rapidly these changes are happening. He documented the largest calving event ever caught on camera, on the Jakobshavn Glacier in Greenland. It was a glacier I spent some time documenting myself. But he was there a few years after I was there, and he documented with video cameras this amazing calving event, where a chunk of the glacier about the size of Manhattan broke off. It is one of the most extreme, worrying and powerful videos.

There was another photographer who had a similar project to mine, and has done a lot for climate change communication: Gary Braasch, from the United States. Tragically, he died whilst documenting coral bleaching on the Barrier Reef in Australia.

You are quoted as having said: “These days, the world has a camera.” How can the rapidly changing world of photography and communication in general – whereby users are becoming increasingly creative and able to generate valuable content – help build awareness about climate change?

Even if I have put together the world’s largest collection of images about climate change, I’m only one person and there are extreme limits to what a single individual can do. With the invention of the mobile phone and digital photography you can now find people who own mobile phones with a camera even in some of the poorest communities on the planet. So, instead of me flying around the world to document climate change, there will already be somebody there. Whenever disasters or climate change impacts happen, people can document those events through their own mobile phones. It is important that people share this kind of imagery on social media, so that everybody can see exactly what is happening around the world as a result of climate change.

Your images are licensed through your own photo agency dedicated purely to climate change and renewable energy. Who are your customers, who buys your photos and what use do they make of them?

Some of my big customers include WWF, Greenpeace, the United Nations and a lot of newspapers, magazines and TV stations around the world. I could say that the WWF is my biggest customer, as they bought my entire catalogue of imagery for a period of seven years to use for communicating their climate message. This enabled me to finish the project off, which was entirely self funded.

How did you organize your expeditions?

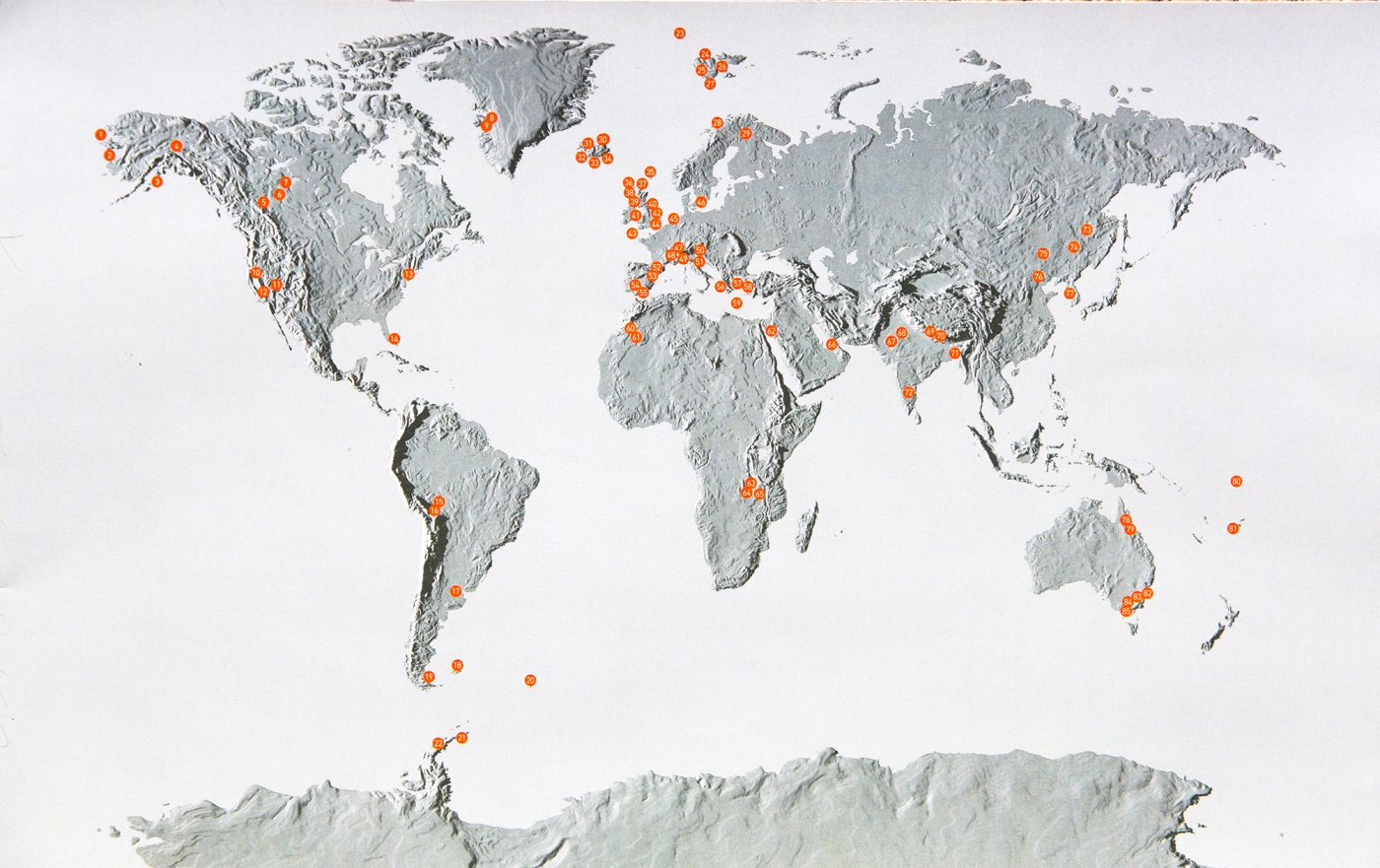

It took me fourteen years to document climate change on every continent. I would typically do four or five photo shoots a year: I would be away from a week – if it was somewhere fairly close to home – and up to six or seven weeks – if I was down in places like Antarctica. I would spend two to three months planning an expedition, making contacts on the ground with climate change researchers, and planning where to go to document what I needed. There was a huge amount of work involved in organizing any given photoshoot.

What are some of the main obstacles you experienced during your expeditions?

The greatest difficulties I had were certainly when I was documenting the causes of climate change, such as when I pointed my camera at coal-fuelled power stations, or big industrial projects. People don’t like you documenting the way they are destroying the planet. I was chased by security guards on numerous occasions. I’ve been stopped by the police more times than I can remember. The worst case was when I went to document the Athabasca tar sands, in Canada. On the very first day, I was stopped by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police who knew who I was and why I was there. They threatened to arrest me and imprison me for three months if I literally stepped one foot off the road to take any photographs.

Other events had more to do with the dangers of the areas I was working in. For instance, I almost fell into a crevasse while documenting the Greenland ice sheet. And I came very close to being caught in an avalanched when I was in the Himalayas: a massive piece of ice detached from a glacier and came about five thousand feet down the mountain, covering the valley floor where I’d been about ten minutes earlier. If I had stayed in the valley floor taking a few more photographs, I would probably have been buried under the snow and ice.

Ashley Cooper is a British photographer with a particular interest in documenting the effects of global warming. A background in natural sciences underpins and informs much of Ashley’s work. In 2010, Ashley was awarded the winning image in the climate change category of the prestigious, world wide, Environmental Photographer of the Year competition. His art photographic book “Images From a Warming Planet” (2016), shortlisted project at the CMCC Climate Change Communication Award “Rebecca Ballestra” (2021), contains the best 500 images from his fourteen years of expeditions documenting the impacts of climate change on every continent on the planet. Ashley’s images are used regularly in books, newspapers and magazines around the world, including front cover images in major UK newspapers.