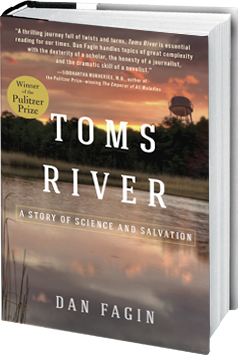

The facts are not enough to make people aware of climate change. People don’t believe in figures, data and graphics. You need more to get their full attention and make them understand you. You need to create a story. Dan Fagin, Professor of Journalism at NYU’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute and Director of the Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program, embodies the role of journalism related to climate change: “The story is part of the success”, explains Fagin when speaking about Toms River: A Story of Science and Salvation, the best-selling book that was awarded the 2014 Pulitzer for General Nonfiction. In the book, the quiet seaside town in New Jersey is transformed by a cluster of childhood cancers scientifically linked to local air and water pollution. Fagin tells the story of several people: scientists, victims, nurses, and a mother who was able to personify the situation. “She was a very sympathetic person. She became a good storyteller, good at explaining from her perspective as a mother, why it was so important to talk about what was happening. She was the storyteller, not me”, says Fagin when talking about how storytelling can help us address complicated issues such as climate change.

I’m very interested in understanding how people relate to nature and how nature changes in the human-dominated space.

We met Dan Fagin in Venice at the Festival for the Earth (December 3-4, 2018) where he gave the talk: Connecting Dots and Chasing Butterflies: Science and Storytelling in a Dark Time.

In the last thirty years, the scientific knowledge of climate science has made great advancements; we know much more today then we knew in the Eighties. How has journalism changed in sharing this knowledge with people and explaining how much it will impact our societies, economies and environment?

“Thirty years ago, we had a pretty primitive understanding of the social sciences and how people form their beliefs. We believed that if we simply reported the facts related to climate change, if we just outlined the modeling, if we explained the greenhouse effect and basic physics, then that would be enough and people would say: ‘Ok, we need to decarbonize the economy, we need to move onto renewables.’ However, this is not exactly how people’s minds work. Social scientists define it as the deficit model: when you think that people are like empty vessels and, if you just fill them up with information, they will believe you.

Nowadays, we know this is not what people are like at all. If you talk to someone who denies the human impact on climate change and you give them a lot of information about this topic, they will use that same information to reinforce their beliefs. We all have a strong confirmation bias.”

In our everyday life, we are all affected by the tendency to process information in a way that makes what we are hearing consistent with our existing beliefs. How is journalism dealing with this?

“One of the ways in which journalism has changed is that we no longer believe that if we just report climate change data, then everyone is going to agree with us.

Enlarge

https://danfagin.com/

Instead, the journalists that are having the greatest impact on their work on climate change have chosen to tell true stories of people impacted, presenting them with empathy. Their work is building an understanding in the broader public that, whether you believe in climate change or not, the weather is changing, it is affecting people’s lives, and we need to help these people. If journalists are able to work this way, they are more likely to make a difference and bring positive change. In my experience, the best climate writers are aware of this.”

Social media can help spread good stories and share them with large communities. At the same time, social media seems to be a breeding ground for the circulation of fake news.

“There is very good research suggesting that most of the people who read fake news in the weeks before the US election were already inclined to vote for Trump. It is not clear that fake news actually swayed many votes. Instead, it is about confirmation bias and reinforcing preexisting opinions: people got more information that supported their pre-existing vote orientation. Therefore, although fake news is a real problem that does not have any easy solution, I think that there is also a tendency to exaggerate its impact. I believe that a bigger problem is social media itself. That’s where people rely on each other and mainly on people who agree with them. They always rely on the same network of information, without listening to what is coming from outside. It is a terrible problem that is more pervasive than fake news.”

When talking about environmental journalism and climate change journalism, you often say: “Storytelling is part of the solution.” What do you mean?

“We know that people do not retain dry information and data. It doesn’t resonate with people emotionally. If we want people to remember something, and ultimately act on it, the content needs to come in the form of a story, in the form of narrative, with characters, drama and a connecting thread. Journalism needs all these things in order to be impactful and make a difference in people’s lives.”

There are a lot of good stories about climate change, the solutions that we have available, the knowledge provided by the science on future scenarios, forecasts, what the world will be like in the next decades and what we can do to avoid severe impacts. However, these stories are often characterized by a “doom and gloom” perspective and focus on heavy impacts. Is it possible to find a way out of the doom and gloom stereotype?

“It is a problem because if you are a journalist you are committed to the truth. In the case of the climate, the truth is sad; it is not a happy story. Still, there are things that we can do. I think that one of the most important frames is to talk about the concept of resilience and tell stories about solutions and how can we make ourselves strong in the face of climate change. Another important frame is related to the development and economic transition: how can we turn the need to develop a post-carbon economy into something positive? Jobs, innovation and advanced technologies could drive this transition and are some of the reasons that show potential for positive outcomes. A third frame is the concept of control. In the Anthropocene we cannot all remain passive, we have to think about active responses. This is something that should unite all of us: the inspiring and exciting concept of becoming an active participant in fixing the Planet. It is something that could bring a political appeal to our decision makers.”