by Francesco Bassetti and Davide Michielin

Forests, street trees, parks and gardens form a complex and interconnected system whose benefits go far beyond aesthetics. If properly managed they can play a vital role in the climate regulation and biodiversity preservation of urban environments and beyond. This involves changing our conception of urban forests and not seeing them as small and separate islands, but rather as the backbone that bridges the gap between urban and rural landscapes.

Following this approach, the architecture firm Stefano Boeri Architetti, developed the concept of Forest Cities as a way of integrating nature into urban environments. Inspired by projects like the “Bosco Verticale” (Vertical Forest Milan) which revolutionized the integration of architecture and nature, Forest Cities extend this model across entire urban landscapes and therefore also socio economic groups.

“By addressing issues of environmental justice and equity, we aim to foster inclusive and resilient urban environments for future generations,” says Livia Shamir, Head of the Research Department at Stefano Boeri Architetti. “To achieve this, urban green systems require a comprehensive green infrastructure strategy. As architects and urban planners, our primary focus is to develop interconnected green networks, ensuring their seamless integration and sustained health.” An approach that underscores the key role of architects and planner in creating vibrant, sustainable urban spaces that benefit all community members.

What is an urban forest?

Urban forests are the backbone of the green infrastructure that connects cities with their surrounding rural areas. More specifically, the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) defines urban forests as a complex system of more or less interconnected urban and peri-urban green areas. When it comes to cities this means roadside trees, trees in parks and gardens, trees in condominiums, in condominium courtyards or in schools and universities, as well as all the trees demarcating the transition between the city and rural areas.

All these urban green systems need a green infrastructure plan that connects them so that they do not lose their functionality, and to ensure that the benefits they bring for urban communities are amplified.

However, to preserve their functionality and enhance the benefits they provide to urban communities, these urban green networks necessitate a comprehensive green infrastructure strategy that ensures their interconnectedness. This approach not only sustains their ecological roles but also amplifies their contribution to urban well-being.

Why is this connection between the rural and urban important?

Urban forestry can act as a bridge between rural wilderness areas and urban landscapes, providing habitat corridors for wildlife and preserving biodiversity. These green spaces help facilitate the movement of species and genetic exchange, which is crucial for the adaptation and resilience of ecosystems to environmental changes.

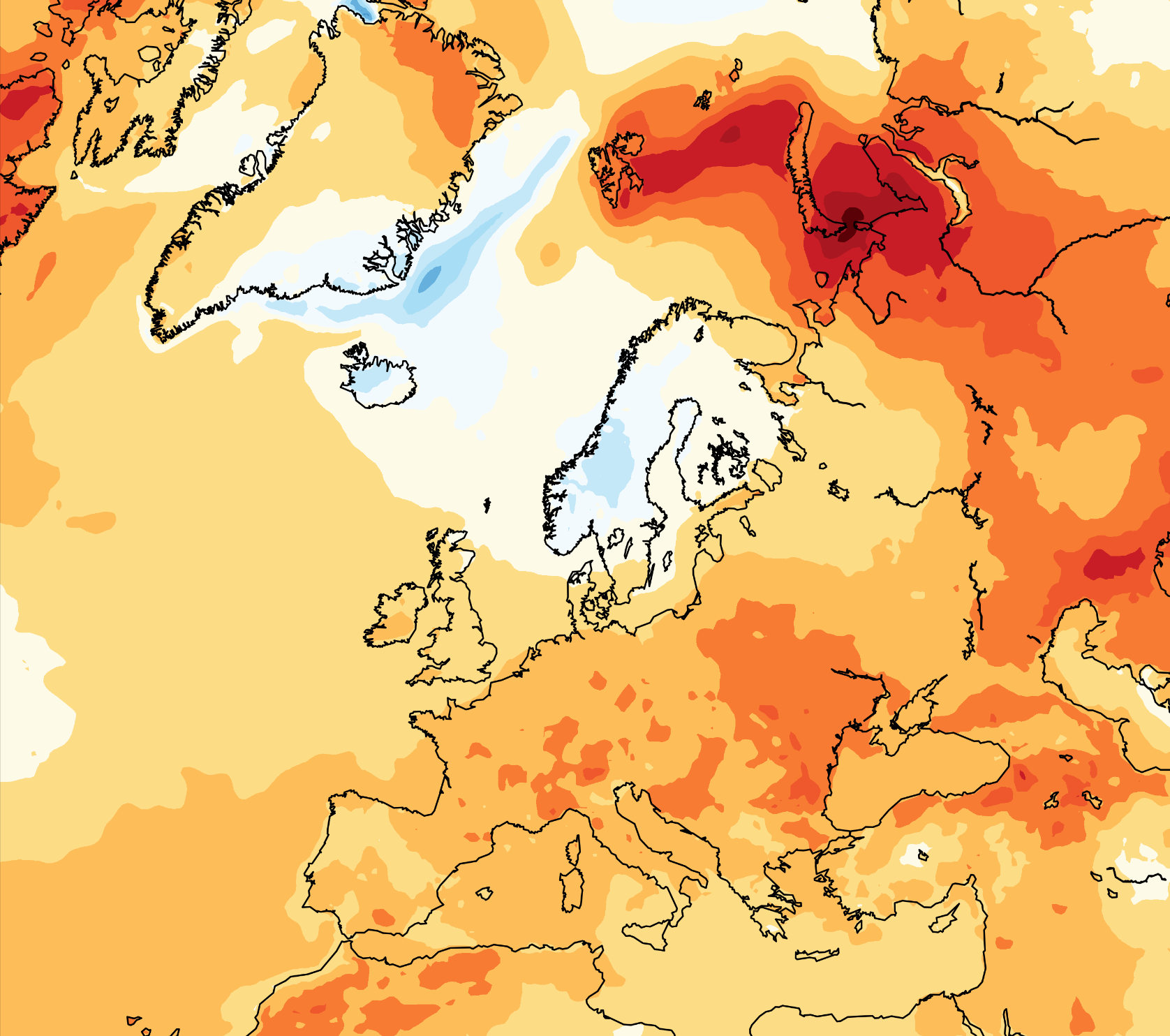

The interconnectedness of ecological systems, is essential for the full functionality of urban green spaces, which offer a suite of ecosystem services with multidimensional benefits. It’s worth mentioning that the types of benefits I’m referring to are mainly related to how they help with regulating our urban environments, particularly in the face of climate change challenges. Urban forests, for instance, play a pivotal role in mitigating the impacts of climate change and reducing risks posed to infrastructure and urban systems.

Their contributions are manifold, including regulating and managing stormwater, sequestrating carbon, and alleviating urban heat island effects through temperature regulation. These benefits are critical in the context of global efforts to combat climate change, highlighting the role of urban areas in broader environmental sustainability strategies.

Acknowledging the rural-urban connection fosters integrated land-use planning, which is essential for sustainable development. It encourages policies that support the mutual benefits of green space in urban areas and the conservation of rural landscapes and wilderness. Furthermore, promoting the rural-urban connection in urban forestry planning encourages collaborative governance, involving various stakeholders in the management of natural resources, leading to more coherent and effective policies that bridge urban and rural needs and priorities.

How did the Forest Cities concept develop? Is it a universally applicable approach to developing green infrastructure?

It all started with the “Bosco Verticale”, which represents a new model of integration between architecture and nature. The next step was to scale up and expand this model to the entire city. The so-called Forest City is an urban model envisioned for specific urban settlements and geographic contexts and conditions, such as the one observed in China before Covid19, when millions of people were moving away from the countryside and into the city.

Obviously, this model is not applicable everywhere. In European cities for example, where the urban context is more dense and consolidated, our projects aim to integrate urban and peri-urban forestry strategies into existing urban plans. A case in point is the Tirana 2030 master plan which consisted of three fundamental elements: a continuous forest system around the city composed of two million trees to preserve local biodiversity and contain land consumption; new ecological corridors along rivers; and an internal forest ring that would serve as a public space.

Another recent example is the Parco Italia project, inspired by the World Park conceived by Richard Weller of the University of Pennsylvania, which aims to gradually establish a national ecological network that connects Italian protected areas, national and regional parks, marine protected areas, and “Natura 2000” sites of community interest through a series of walking and cycling paths that include a high biodiversity of plant species.

With Parco Italia, we started from a large trans-urban vision that aimed to create a vast green infrastructure across Italy, connecting green and high-biodiversity areas with urban centers. In this way, the trans-urban project positions cities or small towns as sentinels and caretakers of the Italian territory and landscape.

A departure from what we would traditionally think of as “architecture”. What sort of research and expertise does this kind of approach require?

We have always had a multidisciplinary approach. When confronted with challenges, we engage with experts from various disciplines, each bringing their expertise on that specific issue. Over time, our collaborations have included foresters, agronomists, climatologists, urban ecologists, engineers, forest ecologists, and experts in mobility and energy strategies. This ongoing dialogue with global experts on a myriad of topics has allowed us to reach a foresight and vision that would otherwise not have been achievable in isolation.

An exemplary case is our recent project that we conducted in the Gulf region, focused on greening and retrofitting within a city where summer temperatures reach up to 60 degrees Celsius. Collaborating closely with agronomists and forestry experts, we identified the most resilient native species suitable for these extreme conditions.

Concurrently, water harvesting experts formulated the best strategies for water collection and salinity reduction. Such multidisciplinary collaboration is pivotal to advancing research, innovation and technological progress in urban sustainability.

How are you tackling issues of environmental and social equity and justice?

Addressing environmental and social equity and justice is at the forefront of our work, particularly exemplified by the evolution of the Bosco Verticale project. This project served as a pioneering model within a specific urban development framework, celebrated for its potential to enhance well-being through the presence of trees, yet initially perceived as viable exclusively in wealthy neighborhoods and users.

We wanted to shift this perception and inspired by the visionary input of our Dutch partner, Sint Trudo, we developed the Trudo Vertical Forest – the first vertical forest of its kind for social housing. It was therefore possible to change the initial model by developing a tower that employed advanced prefabrication techniques, thus reducing construction times and costs and making the green living experience available to a wider audience, including young people, couples, professionals, and students.

Another interesting aspect was the tenant selection process, carried out by the company managing the building. This process prioritized individuals based on income, favoring those unable to participate in the free market yet willing to contribute their time to community initiatives and services linked to the Tower and its vicinity. A great way to change the destiny of the Bosco Verticale for a select few into a shared asset for a broader community.

Livia Shamir is Senior Researcher and Director of the Research Department at Stefano Boeri Architetti. Architect and urban researcher, Shamir is dedicated to the study and analysis of innovative and resilient urban solutions and strategies for climate change, dealing with Nature Based Solutions (NBS), Urban Forestry, and the integration of architecture and nature. Within the Research Department of Stefano Boeri Architetti, she focuses on strategic urban planning projects to address socio-environmental challenges, specializing in sustainability and urban resilience strategies, newly founded cities, urban afforestation strategies, and the design of Nature-based Solutions.

Livia Shamir is Senior Researcher and Director of the Research Department at Stefano Boeri Architetti. Architect and urban researcher, Shamir is dedicated to the study and analysis of innovative and resilient urban solutions and strategies for climate change, dealing with Nature Based Solutions (NBS), Urban Forestry, and the integration of architecture and nature. Within the Research Department of Stefano Boeri Architetti, she focuses on strategic urban planning projects to address socio-environmental challenges, specializing in sustainability and urban resilience strategies, newly founded cities, urban afforestation strategies, and the design of Nature-based Solutions.