Since the industrial revolution, we have relied on fossil fuels to produce energy, in a relationship that has enabled unprecedented global economic growth. However, economic wealth has come at the expense of greenhouse gas emissions causing human-made global warming. To continue Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth whilst stabilising global temperatures, as agreed in the international climate agreements, ‘decoupling’ is the key.

What is decoupling?

In general terms, decoupling indicates a situation in which two or more activities are separated, or do not develop in the same way. When applied to the broad environmental field, it refers to breaking the link between ‘economic goods’ and ‘environmental bads’ (OECD) or, in other words, between economic growth and environmental harm or pressure, as defined by the European Parliament.

There are many possible environmental pressures that can be linked to economic development, from the exploitation of natural resources to the loss of biodiversity or land use. In relation to climate change, the environmental pressure to be decoupled from economic growth are greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and in particular emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2), which is the main gas responsible for the greenhouse effect.

Decoupling is therefore defined in the context of climate change by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as economic growth which is no longer strongly associated with the consumption of fossil fuels, as these are the primary source of CO2 emissions.

A distinction is made between ‘relative’ and ‘absolute’ decoupling. Relative decoupling is where both economic growth and fossil fuels consumption keep growing, but at different rates, with the first growing faster. Instead, absolute decoupling is where economic growth happens but fossil fuel consumption, and thus emissions, decline.

How to decouple economic growth from emissions

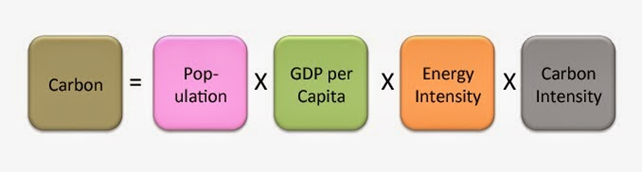

“A key element to understanding what decoupling is and how to achieve it is the Kaya identity,” explains Lorenza Campagnolo, a researcher at the CMCC Foundation and Ca’Foscari University of Venice and expert in the economic assessment of climate change impacts and mitigation policies. “The Kaya identity describes the four drivers of total GHG emission level or growth, i.e. population, GDP per capita, energy intensity (energy used per unit of GDP), and carbon intensity (emissions per unit of energy consumed). Clearly, we observe decoupling when GDP (which is determined by the first two elements in Kaya identity) grows while total GHG emissions remain constant or shrink. This is achievable if the latter two elements in the Kaya identity – namely energy intensity and carbon intensity – decrease.”

The main points of leverage available to reduce energy intensity and carbon intensity are climate policies, which can be tailored to drive the world’s economies towards the use of less carbon-intensive – and, ultimately, carbon-free – energy sources through incentives and regulations.

“Mitigation policies play a key role in energy intensity, stimulating the increase of energy efficiency in the production and triggering behavioural changes on the demand side,” continues Dr. Campagnolo. “Policies are also fundamental in determining structural changes regarding carbon intensity, stimulating the transition from high-carbon energy sources to low-or no-carbon energy (hydropower, nuclear power, wind power, solar power, biomass).”

Are we decoupling?

Global economic growth is rising faster than CO2 emissions and according to the Global Carbon Project this has been happening at least twice as fast over the past 20 years. This means that relative decoupling at a global level has been occurring over the last two decades. However, “it is controversial whether absolute decoupling can be achieved at a global scale,” according to the latest WG3 part of the Sixth Assessment IPCC report, released in April 2022.

We saw absolute decoupling of global CO2 emissions from economic growth happening in 2014-2016, when emissions stabilised while the global economy continued to grow as a result of improvements in energy efficiency, penetration of renewable energy and reduction of coal use.

However, it was temporary. “Longer data trends would be needed before stable decoupling can be established,” states the IPCC in its Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 ºC, in 2018.

Since then things have already changed and after their strong decline due to the lockdown measures imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic, global CO2 emissions rebounded in 2021 as the global economy relied heavily on coal to power its economic recovery.

“Emissions grew and are now already higher than pre-COVID: globally, they are 0.6% higher than in 2019,” explains Johannes Emmerling, co-leader of the Low Carbon Pathways unit at the RFF-CMCC – European Institute on Economics and the Environment (EIEE). “And emissions could grow even higher than GDP this year. Because we see, for instance, that coal is now replacing gas in the power sector, or overtaking wind as the biggest energy producer in Germany because of high prices, which are among the repercussions of the Ukrainian conflict.”

Decoupling is not something that happens, and then you can forget about it, underlines Dr. Emmerling. You need to continue to decarbonise your economy, and things can easily move back once mitigation policies are stopped or reduced.

Production-based and consumption-based decoupling

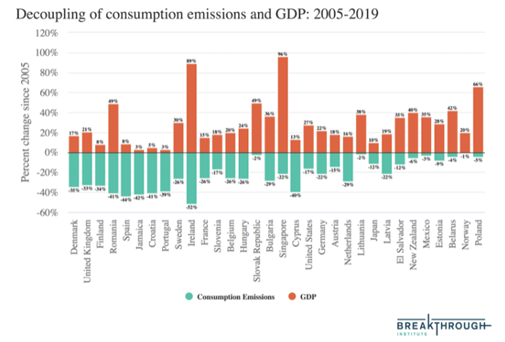

At a country level, over the last few years, absolute decoupling has been reached in many countries, which was a driver of the absolute decoupling temporarily experienced in 2014-2016 at a global level. Countries that decoupled their economic growth from emissions are, by and large, relatively wealthy countries that managed to replace, at least in part, fossil fuels with low-carbon energy.

Change in CO₂ emissions and GDP, UK (decoupling, left) vs India (non-decoupling, right)

“It is not easy to define whether a country has decoupled, because of the many definition issues. It depends on the metric you use,” explains Dr. Emmerling. “For example, there is a difference between consumption and production-based emissions accounting, that should be considered. From a production-based perspective, emissions are counted for the country that produces them. Therefore, a country could import a lot of goods from China or other high emitters, and therefore appear to not be emitting, or even as if it is reducucing its emissions, while still consuming the same goods. Instead, if we use consumption-based emissions accounting, the picture changes.”

In the latter case, emissions are attributed to the country that consumes the goods, which might be different from the one that produces them.

To confirm the difference between the two counting systems, a recent study shows that, out of 116 countries considered, 32 (mainly developed countries) achieved absolute decoupling in the period 2015-2018 from a production-based perspective. However, the number changes to 23 using a consumption-based perspective.

“Countries with absolute decoupling of consumption based emissions tend to achieve decoupling at relatively high levels of economic development and high per capita emissions,” reads the latest IPCC report in chapter 2.3.3. “Most countries of the EU and North America are in this group. Decoupling was not only achieved by outsourcing carbon intensive production, but also improvements in production efficiency and energy mix, leading to a decline of emissions.”

Decoupling and alternative scenarios

Is decoupling the only way to reach zero emissions? As long as we assume that economic and population growth will continue in the coming decades, absolute decoupling is essential to achieve a carbon-neutral world, which is needed to limit global warming to the levels agreed under the Paris Agreement.

However, warns the IPCC, absolute decoupling is not sufficient to avoid consuming the remaining CO2 emission budget under the global warming limit of 1.5°C or 2°C. This is because, although absolute decoupling reduces annual emissions, the remaining emissions keep contributing to an increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration. Consequently, “even if all countries decouple in absolute terms this might still not be sufficient and thus can only serve as one of the indicators and steps toward fully decarbonizing the economy and society.”

Moreover, the starting assumption might change. If the objective is not to maximise GDP but to maximise individual wellbeing – which does not rely only on economic factors but also on social, institutional and environmental ones – one should ask whether we are going to be happier as GDP keeps increasing, and what would happen in the long run.

“As a response to these questions, and looking for the best way to achieve a sustainable future, degrowth scenarios, which describe a future in which economic output declines, are being explored by a niche of researchers,” says Emmerling. “In a way, this point of view is optimistic in terms of climate change mitigation: assuming – or hoping – that economic growth will decrease, or even turn negative in the long run, we can rely on less emissions reductions. Indeed, with a strong economy, we need to do much more to reduce emissions intensity to zero or even become negative.”

For the first time, the IPCC talked about degrowth in its report of the second working group “Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability” issued in February 2022, referring to it as a school of thought that is sceptical of decoupling, an alternative perspective on development and a strategy for achieving sustainability.