The global response to address climate change has changed over time. At first, the focus was almost entirely on reducing greenhouse gas emissions to limit global warming and its impacts. Then, when it became clear that some impacts from climate change would have inevitably materialised, adaptation also gained increased attention in the debate. More recently, evidence has emerged that even with adaptation, some severe climate change impacts will be unavoidable and have the potential to affect lives and undermine livelihoods across the world, as well as push vulnerable people, communities and countries to their physical and socio-economic adaptation limits.

Therefore, there is a growing need to tackle residual climate-related impacts, referred to as Loss and Damage (L&D).

What is Loss and Damage?

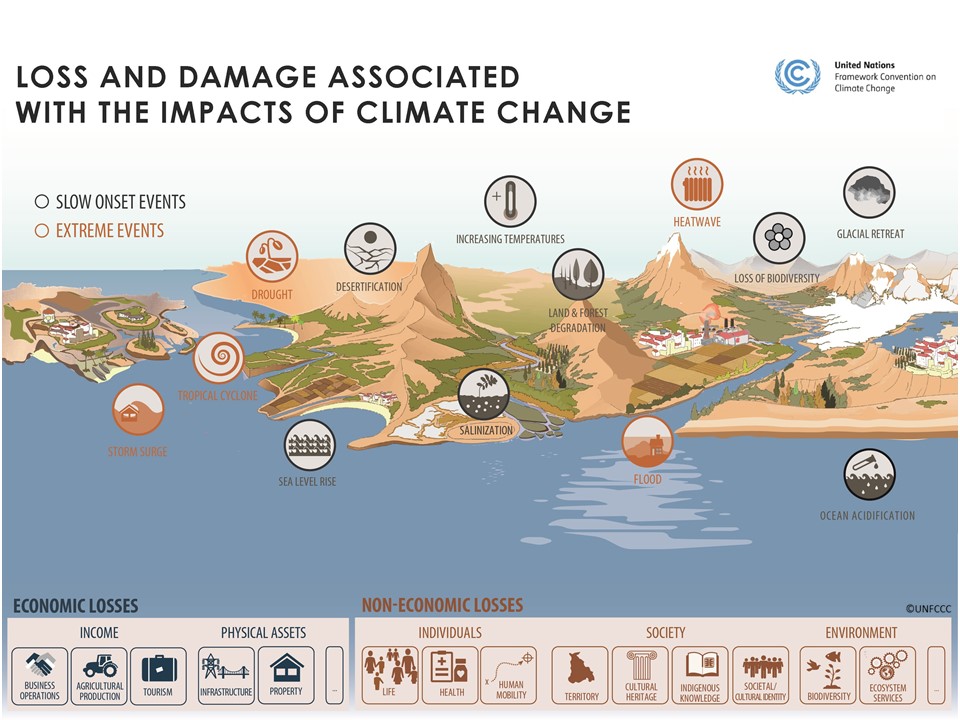

While an official definition under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is still missing, L&D can be broadly referred to as the potential negative impacts materializing in particularly vulnerable developing countries as a result of both slow onset and extreme events* after all feasible mitigation and adaptation measures have been implemented.

L&D includes a wide range of impacts, some of which can be quantified and expressed in monetary terms (eg. impacts on infrastructure or agricultural production) and some of which are increasingly referred to as “non-economic losses” including loss of biodiversity, territory, cultural heritage and identity, indigenous knowledge, and encompassing the emerging issue of climate-induced human mobility.

The concept expands on that of climate change impacts by stressing the unavoidability and irreversibility of certain effects and by emphasizing the role played by constraints and limits to adaptation as drivers of adverse outcomes.

*slow onset events (as referred to in Decision 1/CP.16: sea level rise, ocean acidification, rising temperatures, desertification, loss of biodiversity, land and forest degradation, glacial retreat and related impacts, salinization;

extreme events (just to make some examples): drought, heatwave, storm surge, tropical cyclone, flood

Research on L&D is recent, with the first articles on the issue only being published from 2013 onwards. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) – the most authoritative overview of the state of knowledge concerning the science of climate change – made no reference to L&D and the term appeared for the first time only in 2018 in the Special Report “Global Warming of 1.5°C”, where the Glossary distinguishes between “Loss and Damage” (capital letters) “to refer to political debate under the UNFCCC following the establishment of the Warsaw Mechanism on Loss and Damage in 2013”; and “losses and damages” (lowercase letters) “to refer broadly to harm from (observed) impacts and (projected) risks.

Framing L&D in the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement

The lack of an official definition is due to the political controversies that have characterised the L&D debate since the early 1990s. In particular, it is rooted in requests by the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) for an international insurance pool to compensate vulnerable small island and low-lying developing countries for the impacts of sea level rise. Reference to the contested notion of compensation and responsibility made negotiations between developed and developing countries particularly difficult, and it took more than 20 years to anchor L&D within the UNFCCC architecture through the establishment of the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) in 2013.

As a way forward parties ‘agreed to disagree’ on a strict definition of L&D within the UNFCCC; this constructive ambiguity was helpful in institutionalizing L&D under the UNFCCC while depolarizing the debate.

Elisa Calliari, CMCC@Ca’Foscari

The WIM is the main vehicle in the UNFCCC process to address loss and damage associated with climate change impacts in developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change, in a comprehensive, integrated and coherent manner, by enhancing knowledge generation, strengthening dialogue and cooperation, and enhancing action and support, including finance, technology and capacity-building. The WIM is guided by an Executive Committee (ExCom) in the implementation of its functions.

The Paris Agreement (2015) raised the political profile of L&D by treating the issue in a separate article from adaptation (article 8) and by granting the continuation of the WIM in the post-2020 climate regime.

COP21, further requested the Excom to establish a clearing house for risk transfer, in order to facilitate efforts to develop and implement comprehensive risk management strategies, and mandated the establishment of a task force on displacement, to develop recommendations for integrated approaches to avert, minimize and address displacement.

The current rolling workplan of the WIM ExCom was endorsed by Parties at COP23 in Bonn (2017). Five thematic expert groups play a major role in carrying out related activities**. To date, the ExCom’s work has focused on enhancing understanding and awareness of L&D and promoting collaboration with relevant stakeholders. Delivering on the WIM’s third function on action and support has lagged behind, and the “political” nature of L&D has often been blamed for this.

**1) Expert group on slow onset events (SOEs), established at the end of 2020 – among its experts, Jaroslav Mysiak, director of the research division ‘Risk assessment and adaptation strategies’ at the CMCC Foundation; more information here – ;

2)Expert group on non-economic losses (NELs);

3) Technical Expert Group on Comprehensive Risk Management (TEG-CRM);

4) Task Force on Displacement (TFD);

5) Expert group on action and support (A&S).

Open (political) issues

In the context of the UNFCCC talks and negotiations, views on L&D still vary significantly, and there’s even debate about what losses and damages should be taken into account and why. Key terrains of contention among Parties remain the positioning of L&D governance vis-à-vis the adaptation space (“L&D as within or ‘beyond’ adaptation”) and struggles around questions of justice and responsibility, including state liability and compensation.

The study “Making sense of the politics in the climate change loss & damage debate” highlights the complex and underlying issues that fuel contention within the UNFCCC L&D negotiations. The paper shows that, rather than being a monolithic dispute, L&D catalyses different yet intertwined unresolved discussions. The research identifies five areas of contention, including continued disputes around compensation; conflicts on the legitimacy of L&D as a third pillar of climate action; tensions between the technical and political dimension of the debate; debates over accountability for losses and damages incurred; and the connection of L&D with other unresolved issues under the Convention.

The relationship between L&D and adaptation governance has important implications, as it concerns whether L&D should be considered as something separate and additional to adaptation – therefore becoming the third pillar in the international climate policy process next to climate change mitigation and adaptation-, or as part of it. “Developing and developed countries have historically interpreted this concept very differently”, explains Elisa Calliari, CMCC@Ca’Foscari researcher. “Vulnerable developing countries have historically argued that L&D constitutes policies, activities and finance that are ‘beyond adaptation’ and campaigned for compensation as a key remedy. Developed nations have contested this legalistic framing and strongly rejected any notion of liability. Instead, they have sought to keep L&D firmly within the adaptation realm and emphasized overlaps with the disaster risk reduction (DRR) and humanitarian spheres.”

A political compromise was eventually reached in the accompanying decision to the Paris Agreement (PA), by stating that the agreement’s Article 8 on L&D does not provide a basis for any liability or compensation.

“Calls for liability and compensation associated with the L&D issue”, Elisa Calliari adds, “have always been a real taboo within climate negotiations because developed countries don’t want to open a ‘Pandora’s box’ of endless requests of monetary compensation and remedy for increasing climate-related losses and damages around the world, and in the end this is arguably the main reason why it took such a long time for the L&D debate to be institutionalised under the UNFCCC. The elaboration of a separate article on L&D in the Paris Agreement has provided recognition of the issue in international law and played a key role in signalling the political importance of L&D as an issue. As such, the provision was seen as a significant outcome for developing country Parties. On the other hand, the explicit exclusion of liability and compensation claims under the PA was seen as an important victory for Global North states.”

Therefore, the current approach to L&D in the climate governance architecture remains ambiguous and concerns about the financial implications of addressing L&D persists. As a result, fostering action and support for L&D remain challenging.

The assessment of climate-related hazards, vulnerabilities and coping capabilities has long stimulated convergence between climate change adaptation (CCA) and disaster risk reduction (DRR). The Loss & Damage associated with climate change impacts in fact draws on methods and principles developed by both communities.

Jaroslav Mysiak, CMCC Foundation and SOEs Expert Group

Untold stories of climate change loss and damage in the Least Developed Countries

The way forward

COP25, which took place in Madrid in 2019, established the Santiago Network, which is meant to be a kind of implementing arm of the WIM and aims to connect vulnerable developing countries with providers of technical assistance, knowledge, resources to address climate risks comprehensively in the context of averting, minimizing and addressing loss and damage, at the local, national and regional level.

“L&D has been discussed for more than 30 years within the UNFCCC at the international level”, concludes Elisa Calliari, “In my opinion, the establishment of the Santiago Network is important because it raises a key question: how do these discussions on L&D now translate into activities and practical measures to be undertaken at the national level?”

Parties continued this discussion at COP26, with a focus on how to further operationalize the Santiago network. “Since the Pre-COP there was growing consensus emerging among all Parties that more had to be done to help the most vulnerable countries to cope with the growing impacts”, explains Eleonora Cogo, CMCC senior scientific manager at ISCD – Information Systems for Climate science and Decision-making, “in the end Parties were able to agree on the functions of the Network and to postpone further discussions on the funding arrangements to the next session. During the ministerial segment, there were strong calls to set up a dedicated facility to loss and damage.”

The Glasgow Climate Pact welcomed “the further operationalization of the Santiago network for averting, minimizing and addressing loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change, including the agreement on its functions and process for further developing its institutional arrangements”.

Moreover, the final decision states that “the Santiago network will be provided with funds to support technical assistance for the implementation of relevant approaches to avert, minimize and address loss and damage […] in developing countries […]” and urges “developed country Parties to provide funds for the operation of the Santiago network and for the provision of technical assistance.”

An important achievement of this COP, “a real start of a breakthrough”, Eleonora Cogo comments, was therefore the first mention of a dedicated space to discuss specific funding for loss-and-damage activities. “It represents”, she comments, “a first attempt to change the traditional narrative around L&D, and a recognition that the current options available are not adequate to the scale of the challenge that countries are facing.”

The AOSIS had proposed a “new facility” to support loss and damage with “dedicated financing”, but in the end countries could only agree to the establishment of a Glasgow Dialogue “to discuss the arrangements for the funding to avert, minimize and address loss and damage associated with the adverse impacts of climate change” to start at the next session. A first step which however left vulnerable countries disappointed.

The developed countries; the EU, US and UK, are resisting. It’s important that developing countries don’t fall into the trap of an endless dialogue and are better off deleting all mention of unnecessary dialogues from the text.

— Mohamed Adow (@mohadow) November 13, 2021

“It is getting clearer, as climate extremes and slow onset events are becoming more frequent and severe, that we need to change our focus and narratives in addressing L&D while finding new funds and exploring new solutions, strengthen existing responses such as early warning systems and insurance schemes”, concludes Eleonora Cogo. “But it remains a complicated issue, and it will be crucial to highlight the loss-and-damage financial channels and what solutions to cope with climate change impacts really work in the near future. Developing countries asked for technical support, but also for financial support, and this issue will be at the center of the next meetings in the agenda leading up to COP27”.

References

The Glasgow Climate Pact (pdf)

The section within the UNFCCC website dedicated to Loss and Damage

Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage associated with Climate Change Impacts (WIM)

The Fiji Clearing House for Risk Transfer – the UNFCCC repository of information on insurance and risk transfer

The Santiago Network official website

The paper: E. Calliari, O. Serdeczny, L. Vanhala, Making sense of the politics in the climate change loss & damage debate, Global Environmental Change, Volume 64, 2020, 102133, ISSN 0959-3780, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102133.

The Politics of Climate Change Loss and Damage (CCLAD) project website

CCLAD Repository with a selection of key publications focusing on L&D from a socio-legal perspective.