2019 has been a year of wildfires with global news reporting blazes across the Arctic region, the Amazon, throughout Africa, in California and most recently Australia. Although a natural occurrence, wildfires are being exacerbated by a changing climate that is making them more frequent and intense. By focusing on the role they are playing in Australia and the Amazon we can better understand how and why we must protect this key natural climate solution.

Earlier in 2019, the Amazon region reached global news headlines due to the extensive wildfires experienced in the area. This led to discussions on the importance of the rainforest for the people and biodiversity of the region, but also its vital role in safeguarding the wellbeing of our planet. Often described as planet Earth’s lungs, the Amazon acts as a fundamental carbon sink absorbing between 1 and 2 billion metric tons of carbon every year. As such it can be considered a fundamental natural climate solution and hence an invaluable resource in our efforts to tackle climate change.

Deforestation and man-made fires are threatening to alter Earth’s delicate balance irreversibly. Scientific consensus indicates that if we continue along current deforestation trends the Amazon could reach a dangerous tipping point, transforming the region from climate change buffer into climate change driver. Similarly, extreme weather events connected to climate change are also being causing more frequent and intense wildfires in places such as Australia, that is currently being engulfed in flames.

Understanding the causes and effects of wildfires can help draw light on the potential of natural climate solutions as instruments in contrasting climate change; whereby living ecosystems such as forests, mangroves and seagrass meadows can absorb carbon in a cost-effective manner (particularly when compared to other technology-based solutions). According to George Monbiot, author and Guardian journalist who founded the Natural Climate Solutions campaign earlier this year, “Nature is a tool we can use to repair our broken climate. These solutions could make a massive difference.”

Australian wildfires: a wakeup call

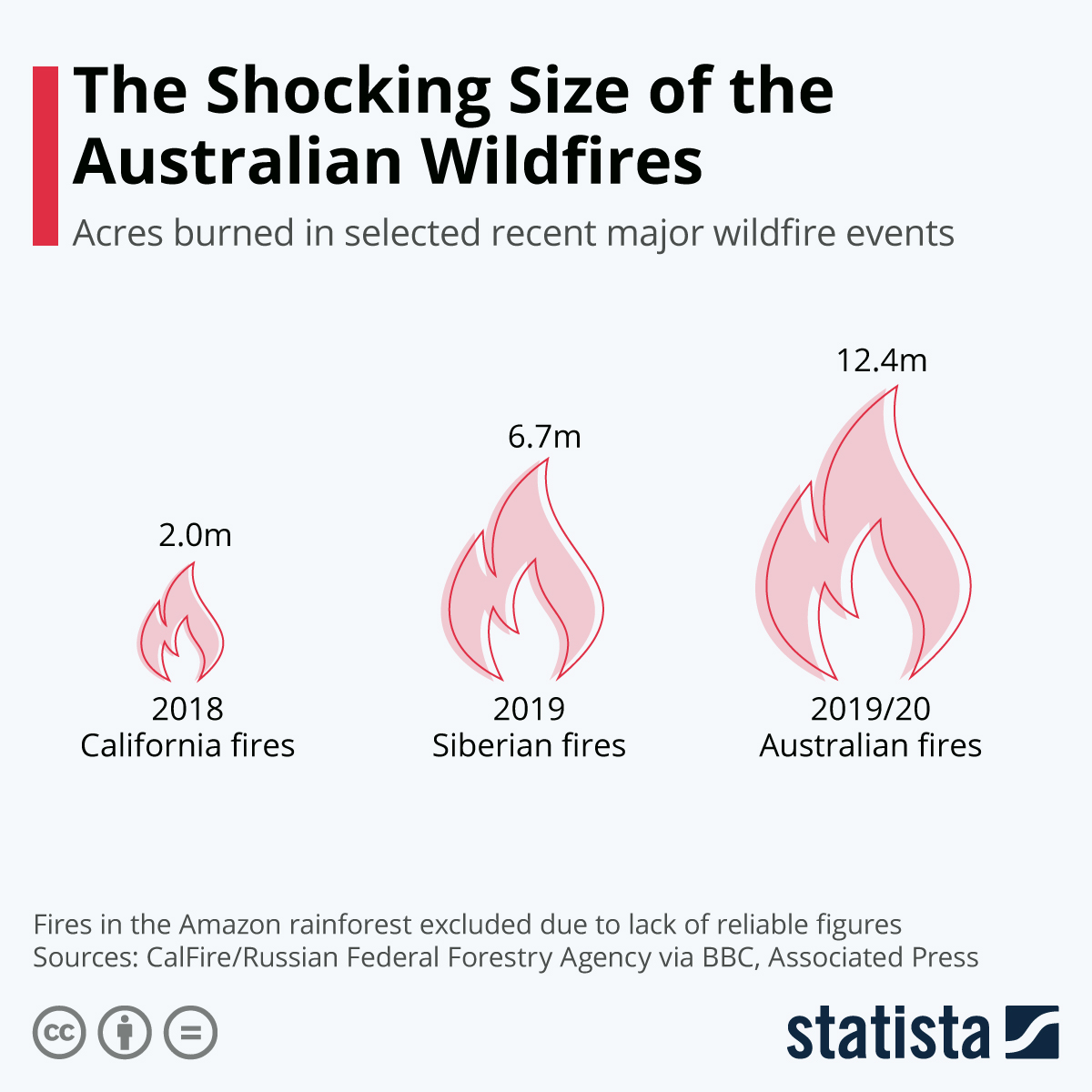

Australian wildfires have blazed their way into 2020, affecting every Australian state, burning bushlands, wooded areas, and national parks; as well as touching large urban centres like Melbourne and Sydney where air quality measures reached up to 11 times the hazardous level. A staggering 5.9 million hectares (14.7 million acres) have burned across the “Land Down Under” for a combined area larger than Belgium and Haiti combined, killing over 20 people and countless animals, burning down in excess of 2000 homes, and emitting more than 250 million tonnes of CO2 (about half of the countries total emissions in 2018).

You will find more infographics at Statista

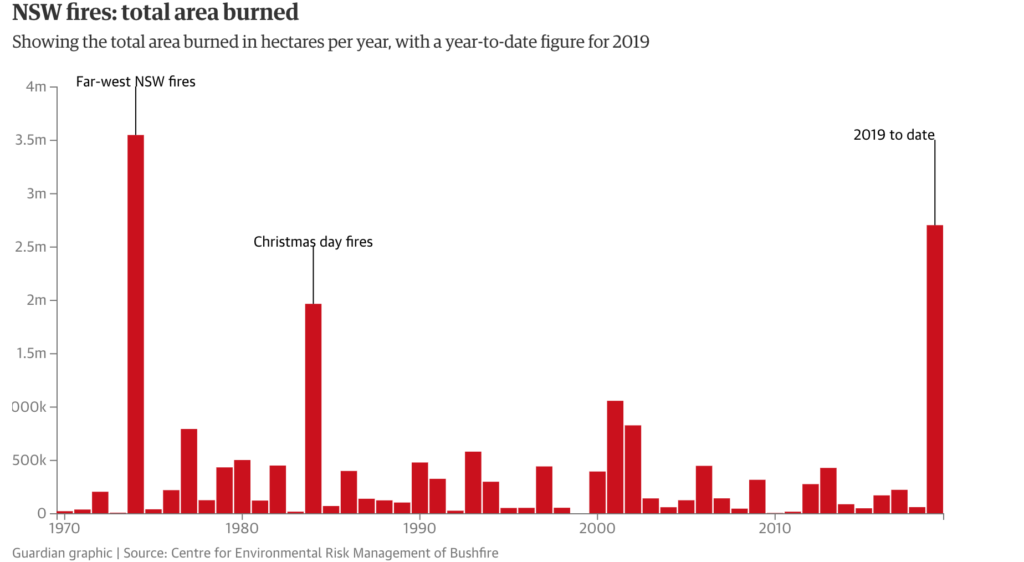

You will find more infographics at Statista

The Australian fire crisis has dominated international news headlines with first-hand accounts of the devastation, fire hotspot interactive maps using NASA satellite imagery and articles denouncing both the Australian government’s response to the crisis and their overall stance on climate change.

Although fires are a natural part of Australian life this year has seen the most intense and destructive fire cycle since 1974. However, in 1974 the fires were largely in remote areas in the outback and burnt through green, non-woody herbaceous plants. They were caused by above-average rainfall which produced ample fuel in outback grasslands. In contrast, in 2019/20 experts indicate that the main cause has been the record heat and drought in the region that has led to a large amount of dry fuel becoming available. In some regions, such as New South Wales (NSW) and Queensland, rainfall between January and August 2019 was the lowest on record.

According to Ross Bradstock, Director of the Centre for Environmental Risk Management of Bushfire, “For the forests and woodlands in the eastern half of the state, this is unprecedented. Natural features in the landscape which often impede fires, like these wetter forest communities, are just burning. There is likely to be long-term ecological and other environmental consequences.”

The change in types of fire and areas that are burning has led scientists to make strong connections between the current fire crisis and the role that climate change is having in exacerbating them. Although no single fire can be linked directly to climate change, the rise in temperatures, drought, worsening fire seasons, extreme bursts of fire weather and behaviour and the spread of fire across the country all align with scenarios painted by climate change projections and indicate that climate change is having a direct effect on bushfires.

What is more, CO2 emissions from fires in grasslands and savannahs are absorbed in only a few years, whereas forested areas take much longer to regrow and hence absorb the CO2 emitted in the fires. According to Dr Pep Canadell, of the CSIRO climate science centre and the executive director of the Global Carbon Project, “it is important to understand both risks – the emissions from fires but also the potential long-term loss of CO2 sink capacity of the terrestrial vegetation due to the incomplete recovery of burned landscapes due to permanent degradation. These emissions are very significant.”

The destruction caused by fires in Australia is painting a bright picture of the effects of climate change on local populations of both animals and people. However, it is in the Amazon that the truly global ramifications of wildfires are most evident.

What happened in the Amazon

The Amazon is one of our most precious resources as a carbon sink, as well as a biodiversity and cultural hotspot. However, up until late October 2019, it continued to burn at an alarming rate.

Almost 75,000 fires in the last year alone, with the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research (INPE) signalling an 83% increase in fires compared to the same period last year. This amounts to over 2,141 square kilometres of forest cover going up in smoke in the first half of 2019, almost 40% more than in the same period last year; of which 1,700 square kilometres burnt in August alone (220% more than in 2018).

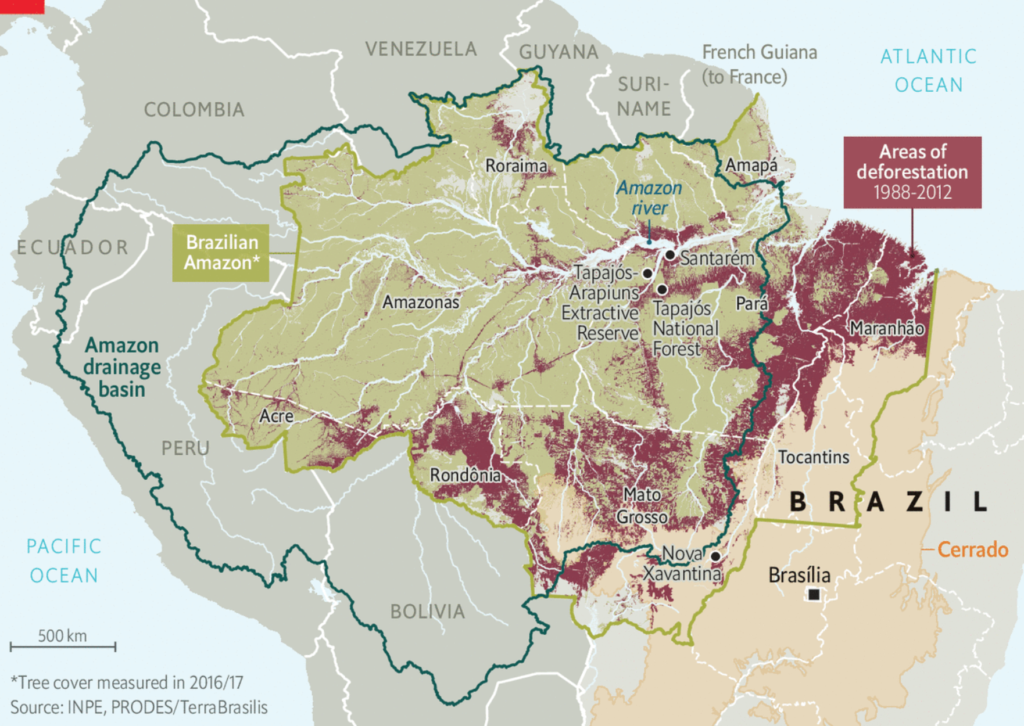

So what is causing these fires? Experts claim that although the dry season creates a more susceptible environment for fires to catch and spread, the primary cause is human activity, and in particular farmers clearing forests for more land. According to Vitor Gomes, environmental scientist at the Federal University of Pará in Brazil, “The dry season certainly adds to fires, but we had more intense dry seasons in the past […] and never experienced such big fires.”

When interviewed for this article, Mikaela Weisse, manager at the Global Forest Watch Programme at the World Resource Institute, also pointed the finger towards human activities: “The fires we are seeing are most likely a result of human activity, whether as part of the process of clearing forests, or for management of cropland and pastures. While we don’t yet have quantitative data on the subject, it appears that most of the recent fires in the Amazon are happening along previously deforested areas.”

The role of policies in the crisis

It is widely recognised that increased regulation was the driving force that brought deforestation to a record low in 2012. At the same time, the relaxing of these regulations is one of the main factors in the steady rise in deforestation since then. Mikaela Weisse explains that “According to data from NASA, available on Global Forest Watch, Brazil had more fires between January and August 2019 than during the same period in any year since 2010.” A trend that has capitulated with the Bolsonaro administration and his rampage (and even personal battle) against the government administrations responsible for environmental protection.

In 2012 Bolsonaro was even caught fishing inside the Tamoios Ecological Station, a federal marine reserve just off the Rio de Janeiro state shore. One of the officials who caught Bolsonaro was José Olímpio Augusto Morelli, who works for IBAMA, Brazil’s environmental enforcement agency. Bolsonaro’s personal feud with Morelli ended with the latter being discharged from his post as head of Air Operations Centre, a crucial branch that coordinates airborne raids on illegal mining and forestry in the Amazon.

Bolsonaro himself was recently elected on a platform that promised to open up the Amazon for development, often speaking critically of environmentalism and both national and international organisations involved in conservation efforts in the Amazon. Whilst encouraging more farming, mining, and logging in the Amazon, the current administration slashed IBAMA’s budget by 20%, resulting in the number of fines issued by IBAMA sinking to their lowest level since 1995, just as deforestation has increased exponentially.

Furthermore, on February 28th the environment minister, Ricardo Salles, carried out a purge in the IBAMA hierarchies, firing 21 of IBAMA’s 27 state heads, on the back of the president’s orders to “clean out” the agency. With most posts still to be replaced, lack of funding and inability to issue and enforce fines it is no coincidence that man-made wildfires have been proliferating in the region.

Why is the amazon being deforested?

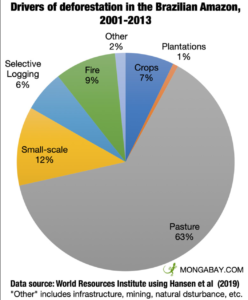

Possibly the biggest contributing factor for deforestation in the Amazon is the agribusiness sector. As global consumption of meat continues to increase so does the need for grazing lands and land for growing livestock feed.

Agribusiness in Brazil contributes to almost a quarter of the country’s GDP, and there are over 50 million cattle in the Amazon alone. Thanks to the Bolsonaro administration’s support for the sector, and spurred by global demand for livestock and feed, Brazilian agribusiness is creeping further and further north, burning the forest to make way for crops and cattle as they go.

“Today 19% of the forest has been deforested and replaced primarily with soy plantations,” Rômulo Batista from Greenpeace Brazil declares. In fact, around 8 million tonnes of soy are exported each year primarily to be used as cattle feed, and it is estimated that cattle related activities are responsible for around 80% of deforested lands.

To make matters worse, in June, Mr Bolsonaro published a decree which indefinitely extends the 2019 deadline for farmers to begin replanting illegally deforested land. This not only reduces the chances of reforestation, it also reinforces the message that the government will turn a blind eye to any further deforestation and appropriation of deforested lands.

The tipping point

A unique characteristic of the Amazon is that it produces a substantial part of its own rainfall. The trees recycle the moisture coming from the Atlantic and around half of the forest’s rain is reused like this. Rainwater is in turn pumped up from the ground by the tree roots where it is released into the atmosphere only to fall as rain again, providing water and a local cooling effect for the region.

The idea of a tipping point is characterised by the fact that this process relies on a critical mass of rainforest so as to maintain the cycle. Too few trees would lead to a loss in ability to recycle the water and in turn bring the rest of the rainforest to suffer from water shortages, increased heat and more susceptibility to fires.

In fact, the University of Leeds predicts that sustained deforestation in the Amazon would cause rainfall to drop by 12% in the wet season and by 21% in the dry season by 2050. A prospect that more and more experts are beginning to deem realistic and leading to claims that the Amazon rainforest would become the Great Amazon Savannah.

The tipping point for the Amazon is believed to be at around 20-25% deforestation. Alarmingly, around 15-17% has already been cleared which leaves us dangerously close to the point of no return. According to Carlos Nobre, a Brazilian climate and tropical-forest expert, “fifty to sixty per cent of the forest could be gone over three to five decades […] If this process continues it will become irreversible.”

“fifty to sixty per cent of the forest could be gone over three to five decades […] If this process continues it will become irreversible.

Losing the Amazon would have serious local and global consequences. The Amazon stores up to 120 billion metric tons of carbon, amounting to around 12 years of global emissions at current rates. If lost, much of that carbon will be released into the atmosphere. Enough to push the global climate beyond safe limits. The Amazon is a vital cog in the planetary system and safeguarding it would mean investing in a fundamental natural climate solution that can provide convincing answers to the current carbon conundrum.

Natural climate solutions

According to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, wildfires have led to a clear spike in carbon monoxide emissions as well as planet-warming carbon dioxide emissions, posing a threat to human health and aggravating global warming. Denise Weisse explains that “Fires release carbon emissions into the atmosphere as they burn. Those that take place on high carbon areas like peatlands or intact forests are particularly concerning for carbon release, and there is evidence that forests don’t fully recover in terms of carbon storage even 15 years later. Over the past five years, the carbon emissions from forest fires in the Brazilian Amazon have surpassed those from deforestation.”

Fortunately, science is progressing rapidly in terms of identifying land-based natural climate solutions. Focusing on strategies that help conserve carbon-rich lands — such as forests, wetlands, mangroves and peatlands — improved forest and grazing-land management, and systemic changes in food production and consumption could potentially eliminate more emissions than a wholesale transformation in the transportation, electricity and heating and cooling sectors.

Climate change is a global problem, and it requires solutions on a global scale. One of those is hiding in plain sight. Our lands provide an untapped opportunity – proven ways of both storing carbon and reducing carbon emissions in the world’s forests, grasslands and wetlands: natural climate solutions.

Planet Earth’s natural assets can contribute to slowing down climate change in important cost effective ways:

- Reduce greenhouse gas emissions, such as carbon dioxide (CO2), related to land use and changes in land use

- Capture and store additional carbon dioxide from the atmosphere

- Improve the resilience of ecosystems, thereby helping communities adapt to the increase in flooding and dry spells associated with climate change

Conserving and bolstering natural climate solutions is therefore an essential part to contrasting climate change which can be achieved with effective policy measures.

Effective policies in some countries have already been proven to work. Mikaela Weisse claims that: “Indonesia offers an interesting example of what can be done to prevent tropical forest fires. After intense fires in late 2015 that caused massive impacts to human health and emissions, the government took several actions to prevent future fires – banning peatland conversion, putting more resources into law enforcement efforts, focusing on fire prevention, and continuing a moratorium on development in forest and peat areas […] so far it looks like those policies have been working.”

Making sure the public outcry caused by wildfires is used to gain support and funding for conservation, wildfire prevention and the promotion of nature based solutions is essential. In particular, climate activists claim that natural climate solutions only receive 2% of funding, so increasing funding towards policies and measures for their promotion can make a significant difference.

Furthermore, although some steps towards stopping wildfires in the Amazon have been taken, more has to be done: “The ban on the use of fires [in the Brazilian Amazon] is a positive start. We need to keep a close eye on the fires and the enforcement of this ban over the next few months” explains Denise Weisse.