On April 10, 1815, on the island of Sumbawa in the Indonesian archipelago, a volcanic explosion occurred so powerful that Thomas Stamford Raffles, the lieutenant-governor of Java – who was almost 800 miles away at the time of the explosion – reported that “the sound appeared to be so close, that it seemed near at hand”.

In the immediate aftermath of the eruption British authorities throughout the region also wrote similar reports, often confusing the sound with cannon fire or the explosion of other volcanoes that were closer by.

Mount Tambora’s eruption was unimaginably violent, causing the mountain to collapse onto itself, obliterating most villages on the island and instantly killing around 12,000 people due to the pyroclastic flows and tsunamis which ensued.

Even more deadly however, was the amount of ash and dust particles that were propelled up to 25 miles into the atmosphere, covering an area almost the size of the USA in a matter of days.

“The darkness was so profound throughout the remainder of the day,” wrote the commander of the Benares, a cruiser of the British East India Company that was in the area, “that I never saw anything equal to it in the darkest night; it was impossible to see your hand when held up close to the eye.”

Temperatures in the region dropped drastically due to the lack of sunlight and as the heavier ash particles fell from the sky, towns up to forty miles away were blanketed in such a thick layer that roofs were said to have collapsed under the weight.

Ash which would also kill thousands in the months to come through respiratory disease, contaminated drinking water, and eventually crop failure and famine. It is believed that almost 100,000 people were killed as a direct result of the eruption of Mount Tambora. By far the deadliest eruption in recorded history.

Using the volcanic explosivity index, which measures the force of volcanic eruptions from a scale of one to eight, Mt Tambora’s eruption was assigned a level seven. To put that into perspective the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland in 2010, which brought air travel across the northern hemisphere to a grinding halt, only garnered a four.

Yet the story of Mount Tambora doesn’t stop in the Indonesian archipelago. Consequences were felt all around the world and offer an invaluable lesson on the interconnected nature of our climate system. One that is still being studied today.

The large amount of fine sulfur particles emitted into the stratosphere – the second layer of the Earth’s atmosphere, which sits above the troposphere – drifted around the globe via air currents, mixing with hydroxide gas to form more than 100 million tons of sulfuric acid.

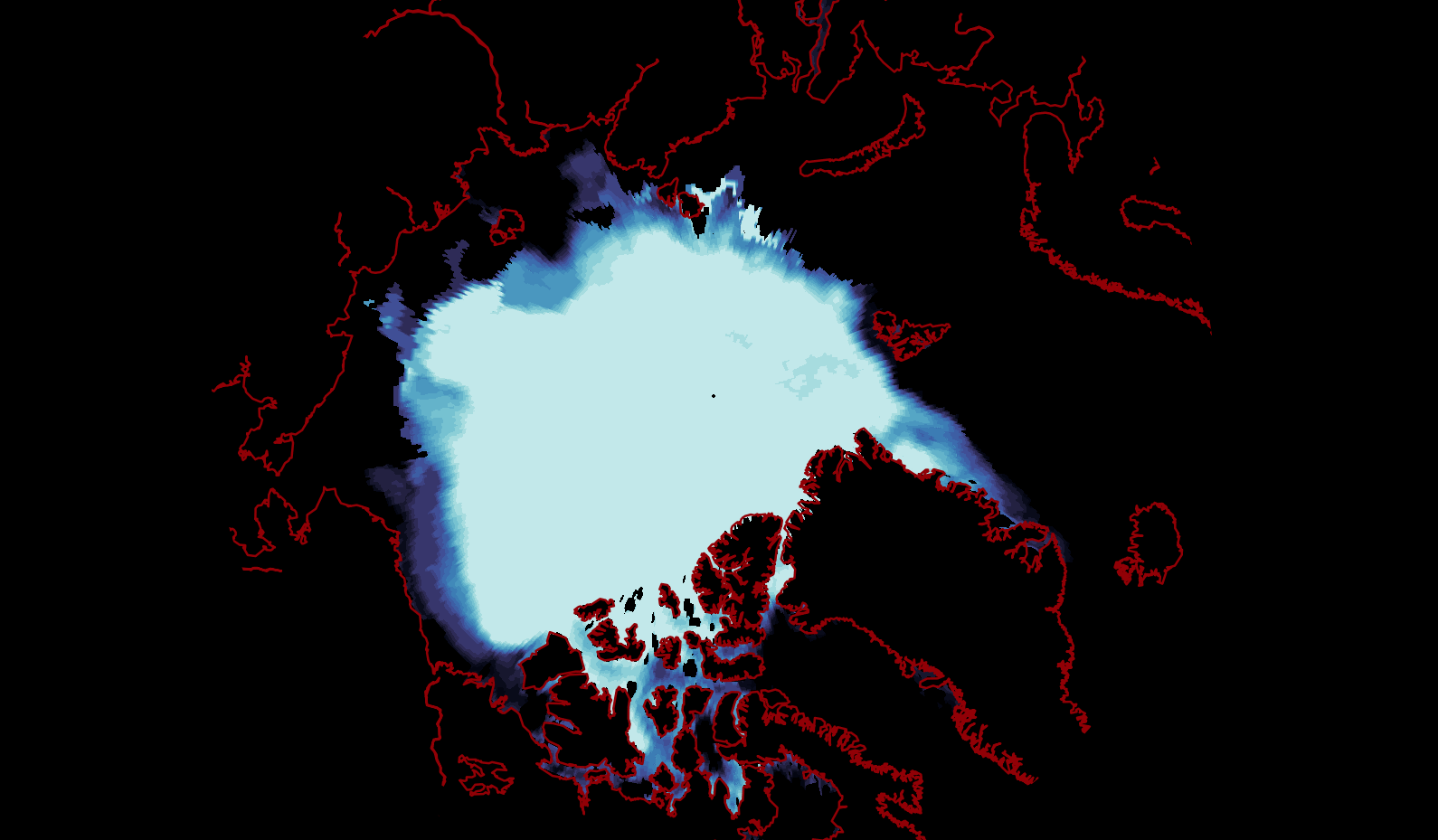

By 1816, imperceptible to the naked eye, an aerosol cloud had formed around the world, reflecting sunlight away from the Earth’s surface, cooling the planet and even altering global weather patterns.

Local eruption global consequences

“Aerosols in the stratosphere are generally speaking reflective, which means that as more sunlight gets reflected back to space, there is cooling at the Earth’s surface,” explains Holger Vömel, researcher at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, USA. “One of the most extreme examples was the Tambora eruption which led to the year without a summer and even caused widespread famine around the globe.”

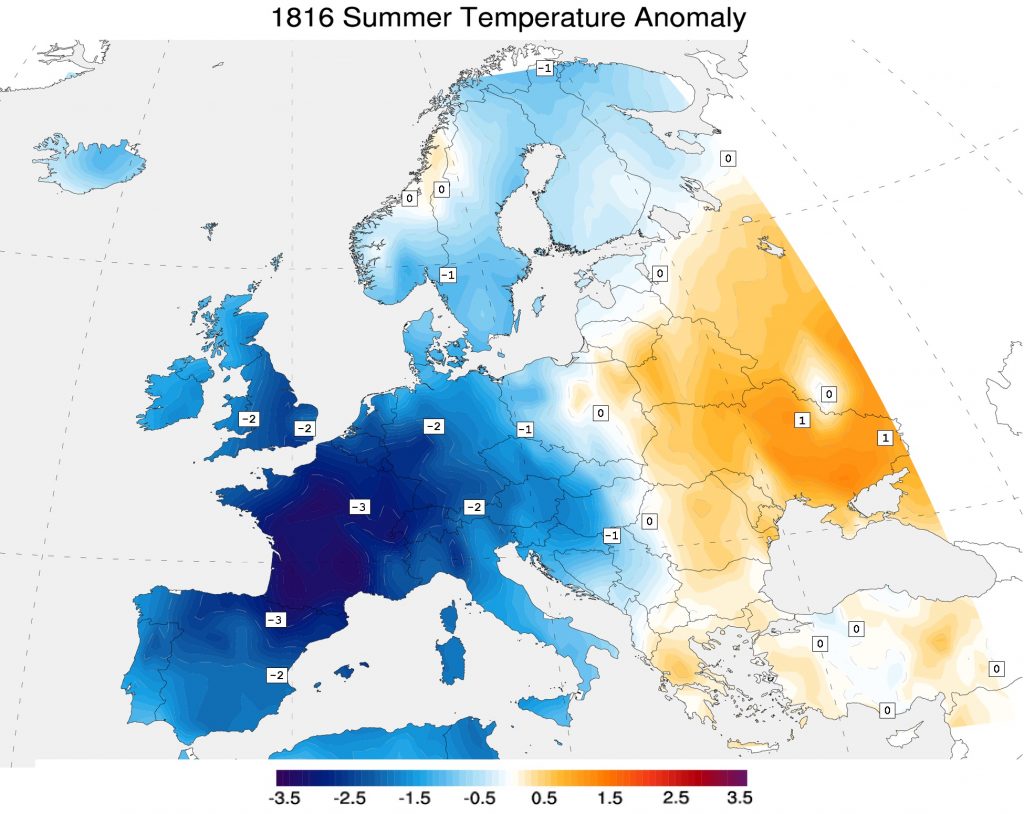

Researchers agree that the year without a summer of 1816 was a direct consequence of the Tambora eruption, with the coldest summer ever recorded in Europe and average global temperatures dropping between 0.4 and 0.7 degrees, causing crop failures and famine in Asia, Europe and North America.

Yet, the global consequences of the eruption are visible not only in the deaths that the eruption caused but also in the art and literature that emerged across Europe and beyond in those years.

The incredible skies depicted by Caspar David Friedrich‘s pieces The Monk by the Sea (ca. 1808-10) and Two Men by the Sea (1817) give a mesmerizing before and after shot of what skies might have looked like at the time.

The “incessant rainfall” and cold of 1816 also confined Mary Shelley indoors for much of her summer holiday in Switzerland and is said to have inspired her writing of the iconic Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.

Volcanoes, humans and climate

Human kind has always been fascinated with volcanoes, and the relationship between volcanic eruptions and the climate is an area of intense research.

“With climate change, there has been a growing interest in how volcanic eruptions change the climate system and in two-way climate-volcano interaction,” says Thomas Aubry, a researcher at the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences of the University of Exeter, where he studies how climatic changes and volcanic processes affect each other .

A popular myth among climate change deniers is that volcanic emissions of CO2 play a greater role in regulating the global climate than those generated by humans. These ideas have been rebutted by scientists in numerous studies that show how volcanic eruptions produce far fewer CO2 than human activities.

“Present day anthropogenic emissions in terms of CO2 are about 100 times larger than volcanic emissions, so in terms of greenhouse warming, volcanoes are negligible compared to humans,” says Aubry.

However, the impact of volcanoes on climate can give scientists invaluable information about what is happening to our atmosphere, particularly when violent eruptions emit large quantities of ash particles and gasses in a single go.

The curious case of Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai

Large volcanic eruptions typically result in global cooling. “Ash particles decrease the amount of sunlight reaching the surface of the earth, and sulfurous gasses combine with water in the atmosphere to form sulfuric acidic aerosols that reflect incoming solar radiation back into space,” says Vömel.

Sulfate aerosols, in particular, are believed to be responsible for the cooling effect as they take several years to be flushed out of the atmosphere and therefore lead to cooling effects over multiple years, whereas ash particles tend to be heavier and hence get flushed out of the lower atmosphere – or troposphere – faster.

“We can see this by comparing tree ring reconstructions and ice core records which show a clear correlation between spikes in volcanic sulfur gasses in ice records and cooling trends in the tree-ring records,” says Aubry. “However, there are exceptions and the recent eruption of Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai is one example that challenges this assumption.”

On 15 January 2022, an underwater volcano in the Pacific Ocean’s Tongan archipelago called the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai erupted violently. With a rating of 6 on the volcanic explosivity index it was the most violent eruption since Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991.\

When the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano erupted on Jan. 15, it sent a tsunami around the world & set off a sonic boom that circled the globe twice. The eruption also sent a plume into the stratosphere with enough water vapor to fill more than 58k Olympic-size swimming pools. pic.twitter.com/dmOjQle6dq

— NASA Climate (@NASAClimate) August 2, 2022

“The Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai eruption was unusual because it released an unprecedented amount of water vapor directly into the stratosphere,” says Vömel, who has been studying water vapor concentrations in the atmosphere since the mid 1990s.

“After the eruption we picked up water vapor concentrations in the stratosphere up to 2,900 parts per million,” says Vömel, who published a paper on the findings in the journal Science. “To put that into perspective, a normal concentration is about 5 parts per million, and even a 5.5 or 6 parts per million reading will get researchers excited.”

For researchers studying the stratosphere the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai eruption presented a unique opportunity. “The sudden injection of a lot of water vapor which we can track and trace is invaluable and allows us to compare actual readings with models and calculations that would otherwise be very hard to validate.”

“I often compare this eruption to a morning coffee,” says Vömel. “If you just stir a plain coffee, it’s hard to tell whether it is spinning or not. But, add a drop of milk to it, and you can suddenly see all the layers swirling around. You can follow each streak and observe how it spreads and moves. That’s exactly what happens in the atmosphere with an eruption!”

Although the long term impacts of the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai eruption on the global climate are still a matter of debate, researchers believe that the large amounts of water vapor emitted into the stratosphere may actually lead to a warming effect as water vapor absorbs heat in the form of infrared radiation from the Earth’s surface and re-emits it.

However, Vömel is careful to highlight how the overall effect on our climate will not be hugely significant. “In five years or ten years down the road, its impact will be over. On the other hand, the impacts of increasing CO2, our main global warming driver, continues. This is the real driver of climate change, not the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai eruption.”

Climate change alters volcanic impacts

Although the impacts of volcanic eruptions on climate change may be, largely speaking, trivial compared to anthropogenic emissions, the impact of climate change on volcanoes is also an area of study which is garnering attention.

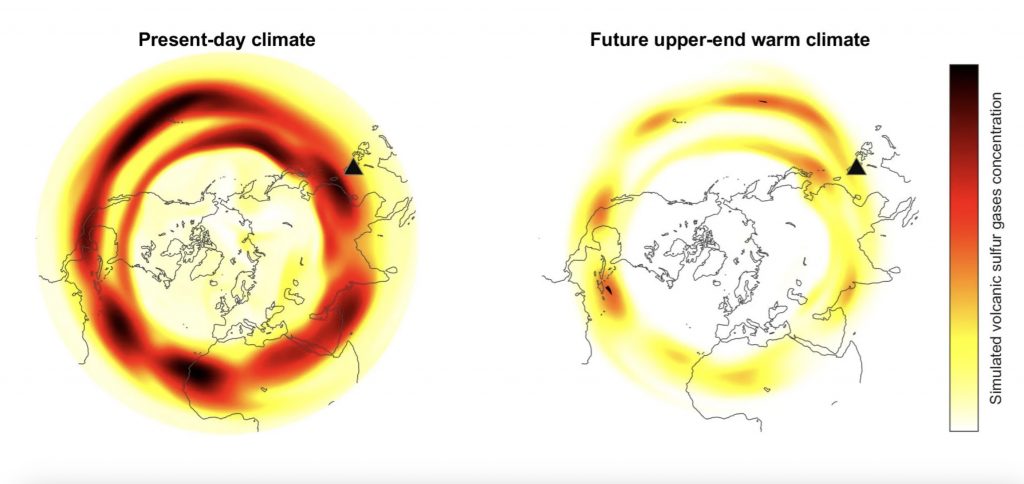

“We know that climate factors such as deglaciation following past climate warming lead to an increase in the frequency and magnitude of eruptions, and now, there is also a newfound interest in how climate change will affect atmospheric processes that govern the life cycle of volcanic gasses and, ultimately, their climate impacts,” says Aubry whose research looks at how a warming climate will impact processes like plume rise and lifetime of aerosols in the atmosphere.

According to Aubry, a warming climate may cause large plumes from eruptions like Mount Pinatubo, which typically occur once or twice per century, to rise higher into the stratosphere and aerosols to travel faster around the world, possibly leading to a 15% cooling effect amplification.

In contrast, the plumes of smaller yet more common eruptions may no longer reach the stratosphere which may lead to a 75% reduction in their cooling effect under a high-end emissions scenario.

“The question that we are looking at now is whether these changes will amount to an overall cooling or heating effect,” says Aubry whose research still hasn’t arrived at an answer to this question, although he expects the overall effect to be minimal compared to other impacts on our climate, such as anthropogenic emissions for example.

“What it is important to realize is how big of a footprint we have on the climate system with all the environmental change we trigger. Our impacts on the climate are so large that they even have the potential to affect volcanic eruptions and processes,” concludes Aubry.

Cover picture:Wikicommons https://www.onthisday.com/photos/eruption-of-mount-tambora