In the wake of the last EU elections, current president Ursula von der Leyen, was responsible for implementing the European Green Deal and hence the climate targets that came with it. However, according to the news feature, bottom-up political pressures mean that Europe’s previous broad consensus on climate action is beginning to fray.

Over the course of 4 days, from 6 to 9 June, people across Europe’s 27 member nations will elect 720 politicians to the European Parliament who will remain for the next 5 years. Polls show that the European electorate is moving towards the right, whose policy priorities are less in line with climate action, which could have significant implications on Europe’s role as a climate leader.

However, climate policies continue to play a fundamental role in EU politics, with suggestions that a green backlash looms in the EU being counterbalanced with recent surveys and reports indicating that climate issues remain a high priority for a substantial part of the European electorate, notwithstanding other competing crises.

Climate concern

According to Euronews.green “obstruction of the Nature Restoration Law is the latest example of a pushback, notably by political conservatives and the farmers whose interests they profess to represent, against the green agenda of the EU executive led by German politician Ursula von der Leyen – who hails from the EPP group and is seeking a second term as Commission president after the forthcoming EU elections.”

However, how important are climate issues on the EU political agenda and how do voters feel about them?

The 2019 EU elections proved to be a key moment for the bloc’s climate policy as Green parties gained an unprecedented amount of support due also to a rise in public concern over the climate. A concern which was best expressed with the large scale youth led protests and led to what some commentators called “the first climate election.”

The result was a strong climate program which included its Green Deal strategy to make Europe climate neutral by 2050 and a huge focus on EU energy and climate legislation. According to Clean Energy Wire, “although the transition to clean energy looks to be unstoppable, it remains to be seen how high the issue will be on the next Commission’s agenda. The incoming EU leadership will oversee the further implementation and development of Green Deal policies.”

Some of the key climate issues faced by the new leadership will be on three main issues: the final adoption of the Nature Restoration Law, the regulation to reduce methane emissions, and CO2 emission standards for heavy-duty vehicles.

Although a final deal between member state governments in the Council and the Parliament on the three issues has already been reached, therefore only missing a final plenary vote, the recent developments in the Nature Restoration Law give an indication of how climate issues may fair if the EU leadership turns to the right as predicted in polls.

Notwithstanding the recent issues with implementation of climate policy, , opinion polls continue to indicate that climate issues remain a key concern among voters. The European Parliament’s Parlemeter 2023 survey showed Policy priorities according to citizens standing at fight against poverty (36%), public health (34%), climate change and support to the economy (both 29%). Similarly, recent findings also show that 77% of Europeans continue to be extremely worried about climate change.

Competing crises

A survey analysis by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) shows that for people in France, Denmark and Switzerland, climate change is the most important of five major crises which Europeans say have changed the way they look at the future.

However, the survey also indicates the “competing existential traumas that run through and between different member states” mean that the 2024 EU election in June could become “a competition between rival fears of rising temperatures, immigration, inflation, and military conflicts.”

Of the five issues highlighted in the report, climate and migration are considered the most mobilizing ones in this year’s election. A case made evident in the recent election result in the Netherlands, which put an anti-immigrant party at the top of the poll and the pro-climate left-wing alliance in second place.

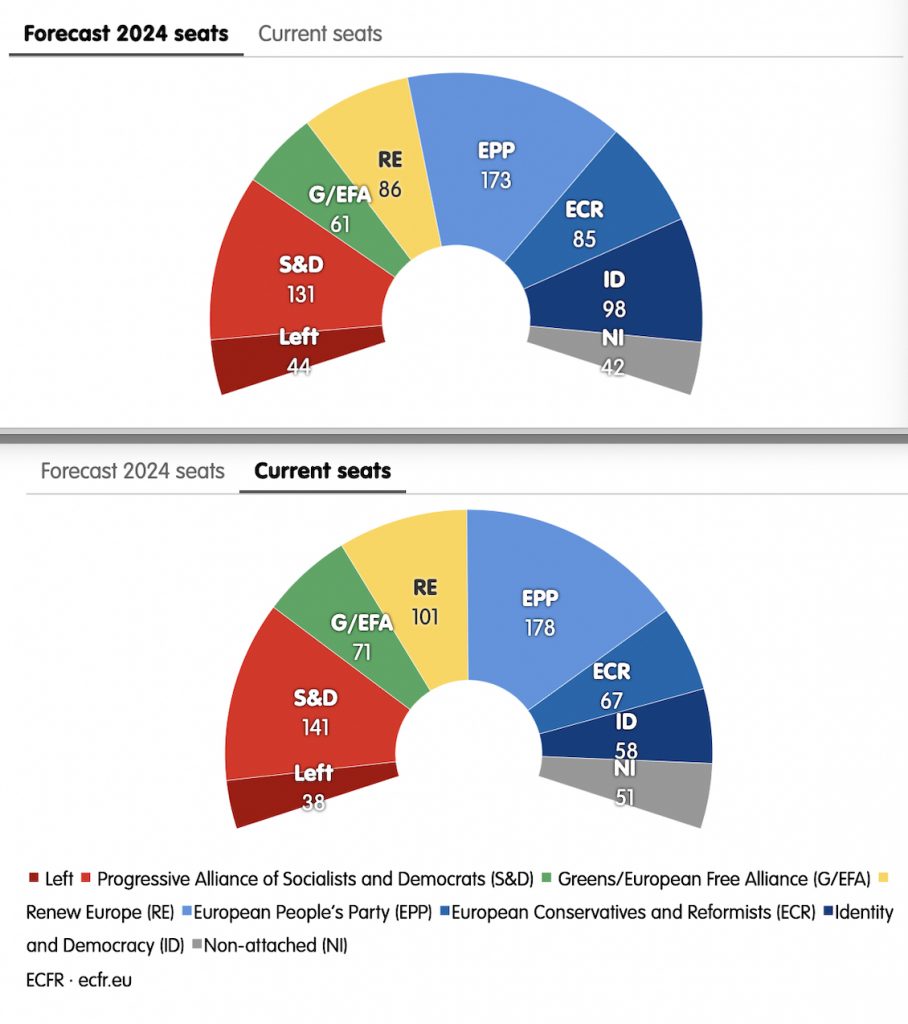

According to the authors of the survey report, “the biggest policy implications of the 2024 European Parliament elections are likely to concern environmental policy. In the current parliament, a centre-left coalition (of S&D, RE, G/EFA, and the Left) has tended to win on environmental policy issues, but many of these votes have been won by very small margins. The significant shift to the right in the new parliament will mean that an ‘anti-climate policy action’ coalition is likely to dominate.”

The fear is that this could undermine the Green Deal framework and hence the continued adoption of policies that will help the EU reach its net zero targets.

With a perceived rise in anti-green sentiment pushing Brussels to relax some environmental rules and anxious politicians scaling back climate ambitions ahead of June’s EU elections, the EU climate chief Wopke Hoekstra told Politico that “In the next term, we need to focus just as much and probably more on climate action,” Hoekstra said, “but also more on the just transition and more on a competitive landscape.”

Green backlash?

“France has seen huge protests against high fuel prices, and could one day elect as president Marine Le Pen, who deplores wind farms and thinks the energy transition should be ‘much slower’. In America climate change has become a culture-war battleground: at a recent debate for Republican presidential candidates, only one admitted that man-made climate change is real.” These are some of the examples given by The Economist as evidence that a green backlash is growing in Europe and beyond.

James Patterson of Utrecht University in the Netherlands told The Economist that anti-green backlashes sometimes occur when environmentalists overreach; for example, by enacting policies so coercive that many people deem them illegitimate.

However, a new report from researchers at Oxford University, Humboldt University Berlin, and Hertie School Berlin seeks to establish if in effect what we are looking at in EU public opinion amounts to a green backlash against climate policies.

Through a survey of 15,000 people across Germany, France and Poland the researchers asked about 40 specific policies to find out which were the most and least popular, coming to the conclusion that in fact fears of a ‘green backlash’ at the European elections are unfounded.

“Taking common armchair diagnoses about a green backlash at face value would be a mistake,” they write, as most voters still support more ambitious climate policy.

“A European election campaign in which parties try to outbid each other over who scales down their climate ambitions the most would simply misdiagnose where voters stand on the issue.”

Instead what the survey reveals is that voters are supportive of policies that target stronger green investment and industrial policies and that in general voters are less opposed to climate action if governments also help those hit hardest by the measures.

Overall, policies and regulations that didn’t directly impact people’s everyday lives tended to be popular. These measures put the pressure to reduce emissions on public authorities and big companies rather than on consumers.

Discussing the issue of climate justice and a fair transition in an interview with the Financial Times Austrian climate minister Leonore Gewessler says, “When we introduced [carbon pricing], we said: ‘OK, we need an answer for how to make this fair.’ It was never meant as a way to collect money, but . . . as a policy to steer towards the more climate-friendly solutions, through pricing.”

It seems clear that fears of backlash are not against climate policies but how they are implemented. Hoekstra concludes that voters in the upcoming EU election still want climate action: “It is not easy but it is doable. We will rise to that challenge and it is what our citizens demand.”