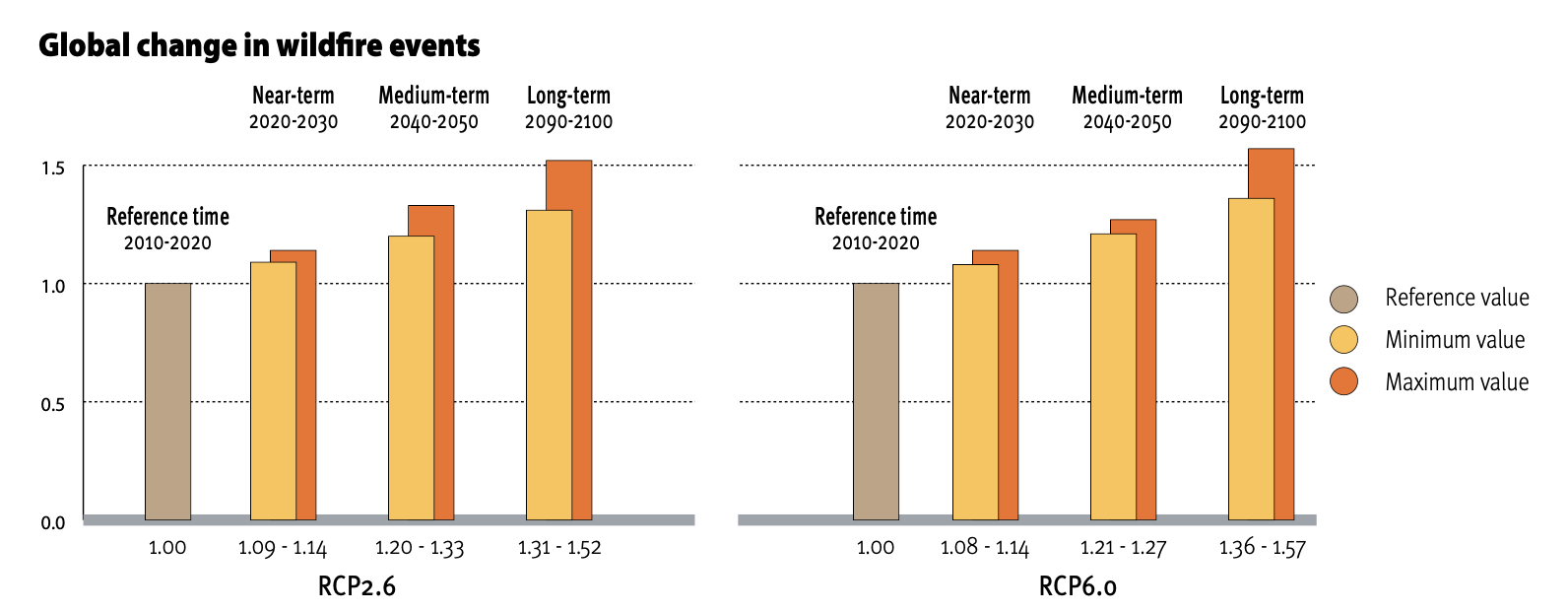

Wildfires and climate change are mutually exacerbating and as global temperatures continue to rise so has the risk of wildfires occurring. According to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and GRID-Arendal, this is just the beginning, with research indicating a potential increase in wildfire events of up to 14% by 2030, 30% by the end of 2050 and 50% cent by the end of the century. Such drastic increases would of course impact the environment but also communities around the world.

“Wildfires don’t stop in the forests. They spread and impact human infrastructure and people,” says CMCC scientist Costantino Sirca, whose home region of Sardinia saw an annual mean burned area over 16,000hectares (1998-2022). “Wildfires with extreme behavior have gone from being a relatively new phenomenon to a regular occurrence across the Mediterranean region. It is the new normal,” he says.

The Mediterranean region is the most impacted area in Europe, with five countries suffering around 80% of burnt surface area and three of the worst fire seasons on record occurring in the last six years. What most concerns experts however is not the occurrence of small and frequent fires but rather what are known as “megafire” events, which are increasingly linked to and exacerbated by climate extremes.

Wildfires are becoming more and more uncontrollable because of extreme climatic conditions that can lead to multiple fire events occurring at the same time which then causes them to spiral out of control. This is due to dangerous conditions on the ground, such as high amounts of fuel, combined with local communities not having the tools and know-how to both prevent or deal with them.

In fact, the increasing scale and frequency of wildfires is challenging the dominant strategy chosen by policymakers to deal with these events. Although there are four phases to tackling forest fires – prevention, prevision, response, and recovery – the largest portion of associated expenditure focuses on response alone. The focus on response has proven to be more more popular with policymakers as it provides more immediate, direct and impressive results: a fire starts, you put it out.

However, the ineffectiveness of a response heavy approach has increasingly come under the spotlight. An influential 2022 report by the UNEP, Spreading like Wildfire: The Rising Threat of Extraordinary Landscape Fires, calls on governments to turn towards a new “Fire Ready Formula”, whereby at least two-thirds of spending be dedicated to planning, prevention, preparedness, and recovery. This would be a stark contrast to the current system that sees direct responses to wildfires receiving over half of funds, whereas prevention receives less than 1%.

Global #wildfires in 2022 generated around 1,455 Mt of carbon emissions. Europe and S America saw the highest emissions in the last 20 years and France & Spain were the worst affected European countries.#CopernicusAtmosphere wildfire monitoring page: https://t.co/oP8i2F0HmQ pic.twitter.com/fjJk7rnk7V

— Copernicus ECMWF (@CopernicusECMWF) January 25, 2023

“Our current approach is contributing to what is known as the fire paradox: the better you get at putting out fires the more extreme they become and the weaker your capacity for prevention,’” says Sirca. Just fighting forest fires contributes to more fuel accumulating in forests, which in turn leads to larger and more extreme events that end up being uncontrollable and having huge impacts on people and their goods.

“The politics of focusing disproportionately on firefighting is not working as the kinds of fires we are seeing today are no longer controllable,” continues Sirca.

Prevention is key

To prevent fires researchers are advocating for a combination of data and science-based approaches as well as on the ground interactions that can help foster stronger regional and international cooperation. The key to prevention is therefore about ensuring collaboration across sectors and stakeholders; an approach that requires long term planning rather than short term reactions.

In this context, CMCC has focused its research strategy on tackling a variety of different aspects related to prevention. One of these is ensuring that communities exposed to fire risk are involved, prepared and resilient. Through projects such as The HuT, CMCC researchers engage in small-scale case studies and ground work with the people who are both most affected by forest fires, but also the ones best equipped to build resilience.

“From talking with owners of campsites, local farmers and even firefighters, the The HuT project focuses on small and targeted actions, as these are the most effective if we are to help build resilient communities,” says Sirca. “You can’t just enter communities and propose grand plans, you need to understand their experiences and perspectives so that we are all speaking the same language.”

Similarly, the FIRELOGUE project, funded under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 program, works with stakeholders to find integrated solutions to the management of fires by linking researchers with civil society organizations so that the experience and best practices of all stakeholders are brought into the picture.

Among these projects is the SILVANUS platform which provides tools for environmentally sustainable and climate resilient forest management by bringing together environmental, technology and social science experts to enhance regional and national capacity to monitor forest resources, evaluate biodiversity, generate more accurate fire risk indicators and promote safety regulation among citizens.

The end goal of these strategies is building communities that are ready and resilient, which implies both knowing how to deal with fires but also how to recover and re-establish balance rapidly and effectively after they occur. In a nutshell, “fire wise” communities that know what causes fires and how to behave when they occur.

An excellent example of the interaction between the research community and civil society organizations can be seen in another Horizon 2020 project, involving the CMCC, that attempts to find solutions to fire risk management in nature itself. The DRYAD project fosters international efforts to evaluate nature based solutions to enhance the resilience and reduce fire risk in agro-silvo pastoral areas in the Mediterranean.

“Agro-silvo pastoral areas are extremely important not only from an economic perspective but also from a social one as they provide crucial ecosystem services that go beyond the realm of simply producing goods,” says Sirca, who sees a powerful tool for long term fire prevention strategies in nature based solutions, as they have the potential to be both environmentally and economically sustainable.

The key is that fire risks are intertwined with the communities and people that live in affected areas and therefore understanding how these communities perceive these phenomena is essential for effective implementation of strategies.

“We cannot eliminate fires entirely, so we have to learn to coexist with them,” says Sirca. “Not to mention that fires also come with benefits to biodiversity and ensuring that forests don’t accumulate fuel that can then lead to much larger wildfires.”

The power of prediction

Another key aspect to fire management prevention and preparedness revolves around the power of prediction, which researchers have been exploring through modeling. From fire danger to fire risk and propagation models there are numerous ways in which modeling can play a key role.

The CMCC’s Impacts on Agriculture, Forests and Natural Ecosystems (IAFES) division – that focuses on the interaction between climate and terrestrial ecosystems – is also involved in numerous fire related modeling projects, including designing and developing modeling capacity so that researchers are able to study the interaction between climate and terrestrial ecosystems in relation to fires.

One example is InterTwin, an interdisciplinary Digital Twin Engine for Science that will help implement a Digital Twin so as to provide near-real time information for the management of emergencies related to a variety of extreme events, including by reproducing and then predicting fire disturbances. This shows how recent developments in artificial intelligence, deep learning and machine learning capacities can provide a valuable new resource in adaptation strategies.

“Modeling helps because it allows you to broaden the scope of your research,” explains Sirca. “With case studies and stakeholder engagement on the ground we look at small areas in detail, but with models you can have a three dimensional view of the territory and assess situations that would otherwise require much more time and money to monitor. Modeling doesn’t turn us into oracles but it does allow us to test solutions because well worked models can help predict the impacts of given activities and strategies.”

For example, the OFIDIA and OFIDIA2 projects offer real-time environmental predictions on the risks of fire development with the help of HD video cameras, wireless sensor networks and drones, so that stakeholders can patrol high-danger and remotely located areas effectively.

“All four phases of wildfire management have to work in unison,” concludes Sirca. “There are contexts where prediction or prevention may be the most effective and others in which it may be response. Overall, it is about coexisting with fires and building resilient communities.”