The summer of 2022 saw almost unprecedented droughts across the globe. From much of Europe reeling under water shortages, to China’s Yangtze River drying up as China baked under a three-month record-breaking heatwave.

Yet droughts were not the only extreme weather event. Over the month of August Pakistan reported over three times its usual rainfall, leading to the wettest month on record since 1961, with two southern provinces even beating that record with seven to eight times the usual rainfall. This led to the Indus river overflowing, as well as urban flooding, landslides and flash floods.

At a recent press briefing, UN Secretary-General António Guterres recalled the devastation he witnessed on his trip to flood-hit Pakistan, which he described as a window into a “future of permanent and ubiquitous climate chaos on an unimaginable scale”.

The flooding has led to over 33 million people being displaced and an estimated 1,500 left dead. The economic toil has also been immense, with initial estimates at 30 billion USD, 6,700 kilometres of roads destroyed, 269 bridges toppled and a loss of food crops for approximately 2.3 billion USD, which adds to the critical food stock issues created by the preceding summer drought and the war in Ukraine.

“We will do our best to financially help you so that you can rebuild homes,” said prime minister Shahbaz Sharif when speaking to families in the town of Sohbatpur in Baluchistan during a televised visit. “Those who lost homes and crops will get compensation from the government”.

However, the question remains as to how exactly the government will pay for all the damages Pakistan has suffered. One of the answers lies in determining how much man-made climate change has to do with the extreme events, and the need for rich countries to deliver on their promise of finance for loss and damage due to climate change.

Both the intense drought and the devastating flooding are clear examples of loss and damage, meaning the loss of lives, land and infrastructure from climate impacts that cannot be recovered, nor adapted to and which countries such as Pakistan have little responsibility for.

Extreme event attribution

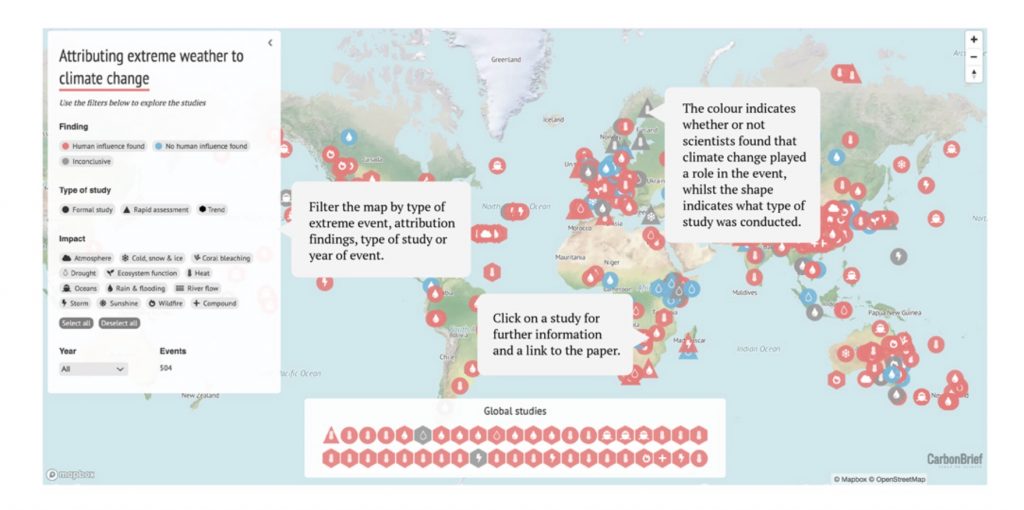

Scientists have started to look at the correlation between the abstract concept of climate and the personal and tangible experiences of the weather in a practice commonly referred to as “extreme event attribution”.

Over 400 peer-reviewed studies that address weather extremes ranging from heat waves and wildfires, to typhoons and monsoons have been published, leading to an increased understanding of the link between human-induced climate change and the risk of some types of extreme weather.

A recent climate attribution study revealed how climate change made the 2022 heat wave across India and Pakistan 30 times more likely versus a world without climate change.

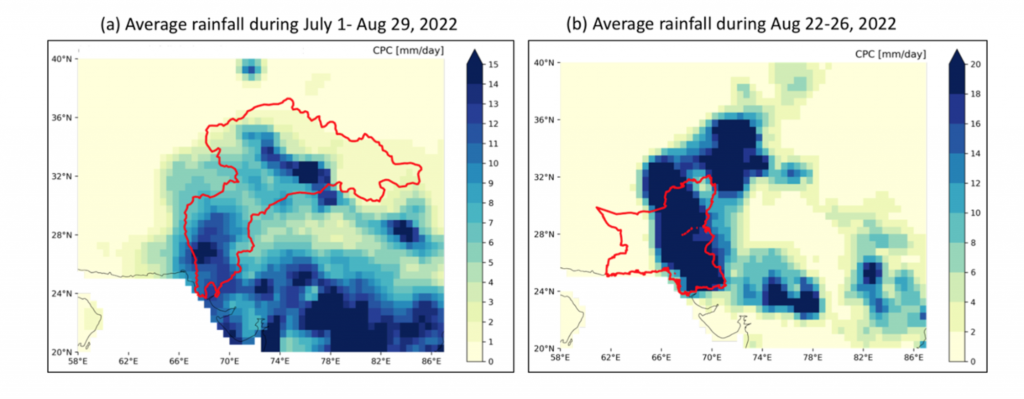

Similarly, analysis of the extent to which human-caused climate change influenced the likelihood of an intense monsoon cycle, which is what ultimately led to the flooding, also appears to be damming. Scientists from Pakistan, India, the Netherlands, France, Denmark, South Africa, New Zealand, the US and the UK used published, peer-reviewed methods to perform an event attribution study, focussing on two aspects of the event: Firstly, the annual maximum of the mean 60-day precipitation during June-September over the Indus river basin, and secondly, the annual maximum of the mean 5-day precipitation in June-September over the worst hit provinces Sindh and Balochistan.

Their studies indicate that 5-day maximum rainfall over the provinces Sindh and Balochistan were made 75% more intense than if they had occurred in a world that had not warmed by 1.2 C.

Although the researchers admit that there are still large uncertainties around these estimates, the pattern is clear and consistent with predictions by climate scientists around the world which show that climate change will continue to generate more intense monsoons and extreme weather events in general.

The most recent example of hurricane Ian, which has torn through Cuba and the US causing widespread destruction, just another case in point.

New data from NASA reveals how warm ocean waters in the Gulf of Mexico fueled Hurricane Ian to become one of the most powerful storms to strike the U.S. in the past decade. https://t.co/bGkewxipVL

— The New York Times (@nytimes) September 30, 2022

Not just Pakistan

The deadly destruction in Pakistan and its connection to man made climate change is no isolated event. Throughout May 2022 and extending into June, eastern northeast Brazil experienced catastrophic floods and landslides following exceptionally heavy rainfall. Scientists at the World Weather Attribution also looked at this event and concluded that “human-caused climate change is, at least in part, responsible for the observed increases in likelihood and intensity of heavy rainfall events as observed”.

Not to mention South Africa, where the president Cyril Ramaphosa, described the flooding as a “catastrophe of enormous proportions”, declaring a national state of disaster on Monday 18 April 2022. Once again extreme event attribution studies point the finger at greenhouse gas and aerosol emissions as at least partially responsible for the observed increases.

What is more, in many cases flooding has been preceded by drought. Hannah Cloke – a hydrologist at the University of Reading explains, in an interview with Wired, that “Soil [that is subject to drought] starts to act like concrete or tarmac. When we get any rainfall on it at all it just runs straight off – it’s classic soil physics.”

A view that is corroborated by other scientists that show how drought across the globe will also leave regions exposed to more intense flooding as soil loses its ability to absorb water effectively.

“It’s really important to remember that we’ve always had floods, we’ve always had droughts, and the main problems come because of the way we’ve changed the landscape, the way we’ve changed our rivers, the way we’ve abstracted water, and we’re overusing the water that’s there. It’s going to get worse with climate change, but there are ways to live with and adapt to these phenomena,” concludes Cloke.

Cover photo: Asian Development Bank on Flickr – Creative Commons: https://www.flickr.com/photos/asiandevelopmentbank/8529842277/