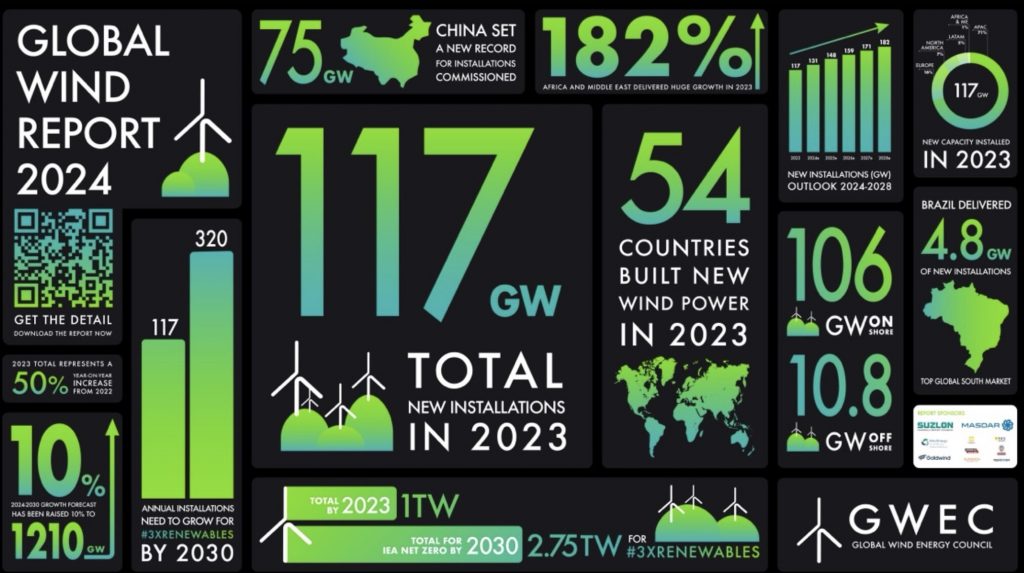

Wind energy generation is increasingly becoming a key player in the transition to low carbon economies. In 2023 alone, the global wind industry installed a record 117 gigawatts (GW) of new capacity — signaling a 50% increase from the previous year.

This is causing a shift not only in the way countries produce energy but also opening new frontiers in international relations; reshaping the dynamics of economic strategies and relations between countries. According to the World Economic Forum “Nations are using wind energy for more than just environmental benefits; it’s becoming a tool for economic and political independence, promising to boost national security as well. This change is elevating wind energy as a major element in global geopolitics.”

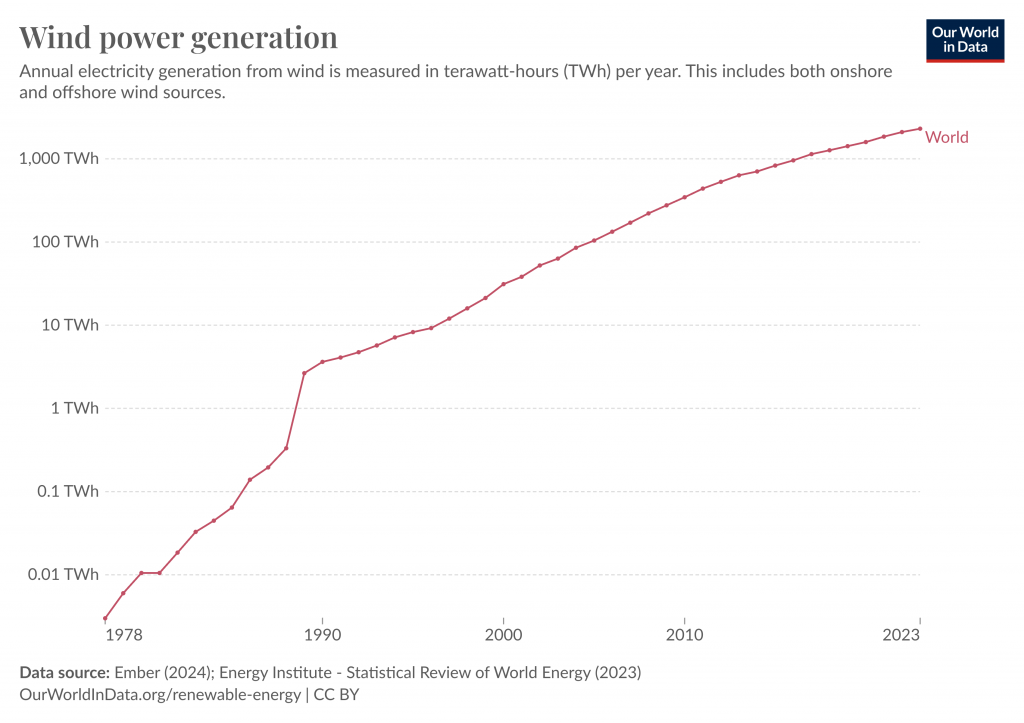

The modern wind power industry was to a considerable extent developed in Denmark in the wake of the 1973 oil embargo, which hampered energy supplies throughout the West. Since then, the growth in wind energy generation has been exponential. In the U.S. electricity generation from wind energy went from less than 1% in 1990 to about 10.2% in 2022. In Europe the growth has been even more pronounced, propelled by financial and other incentives that have led to a large expansion of wind energy generation. However, the current global leader in the industry is China, having invested heavily in wind energy and now ranking as the world’s largest wind electricity generator.

In 1990, 16 countries generated a total of about 3.6 billion kWh of wind electricity yet by 2021, approximately 130 countries generated about 1,808 billion kWh of wind electricity. Notwithstanding this staggering rise, recent developments in the wind industry have seen the pace of progress take a hit.

From issues with supply chains, lack of interconnection and grid infrastructure, rising costs and the effects of troubled geopolitics, total generation has continued but at a slower pace. In the US less wind power capacity has been added each year compared to the years preceding the signing of the influential 2022 Inflation Reduction Act and the EU has also experienced a similar slowdown.

The latest numbers on wind

Each year leading institutes and organizations publish industry reports on the state of wind energy, both onshore and offshore. Among these the International Energy Agency (IEA), the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC), the American Wind Energy Association (AWEA) and the European Wind Energy Association offer some of the most reliable metrics on the current state and future prospects of the wind energy sector.

In 2024, the IEA published its annual report on renewable energy development. In the report, the IEA is even more bullish than previous years on the future role of wind power, claiming that it will become the “predominant” source of power generation in Net Zero emissions by 2050 scenarios. According to the report, wind electricity generation increased by a record 265 TWh (up 14%) in 2022, reaching more than 2 100 TWh – with China accounting for half of global wind power capacity additions.

Yet the report doesn’t just highlight China’s role. It also looks at the efforts of the European Union which has managed to accelerate wind deployment with an additional 13 GW added in 2022. In particular, the REPowerEU Plan and The Green Deal Industrial Plan are highlighted as effective policies and targets in the drive towards further wind power investment.

Another notable mention is the impact of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in the USA which has come with investment and production tax credits that have led to a boost in capacity deployment. Furthermore, the report sees 2023 as a shedwater moment in the USA as the first large-scale offshore wind farms on the American continent are due to become operational on the East Coast of the United States.

On a similar note, the GWEC Gloabal Wind Report for 2024 highlights increasing momentum in the growth of wind energy worldwide. Their analysis shows that in 2023, total installations of 117GW amount to a 50% year-on-year increase from 2022, which led the organization to revise its 2024-2030 growth forecast upwards by 10%, as a result of the uptick in favorable national industrial policies in major economies, gathering momentum in offshore wind and promising growth among emerging markets and developing economies.

In more specific regional contexts the US based American Wind Energy Association (AWEA) declares in its 2022 report that, “Today more than 72,000 wind turbines across the country are generating clean, reliable power. Wind power capacity totals 151 GW, making it the fourth-largest source of electricity generation capacity in the country. This is enough wind power to serve the equivalent of 46 million American homes.”

Wind in the US is currently the largest source of renewable electricity generation, providing 9.8% of the country’s electricity.

In Europe, the European Wind Energy Association (WindEurope) estimates that Wind now meets 17% of Europe’s overall electricity demand, with some countries leading the way – Denmark 55%; Ireland 34%; UK 28%; Portugal 26%; Germany 26%; Spain 25%. The IEA expects wind to be the primary source of power in Europe by 2027.

The EU Commission sees wind making up half of Europe’s electricity by 2050, with wind energy capacity rising from 205 GW today to up to 1,300 GW – for this to happen there would have to be a twenty five fold increase in offshore wind capacity in the EU.

Facing headwind?

Although prospects for the development and growth of the wind industry are positive there are also considerable issues. A study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) by an international team of scientists, including researchers from CMCC, the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), and University of California at Berkeley, looks at the possible impacts of renewable energy projects and how local populations perceive them, by focusing on the impact of wind power generation on local communities.

In another study, led by CMCC researcher Enrico Antonini, historical weather patterns were analyzed to establish what areas are best suited for the development of wind energy projects. Surprisingly, the study found that the North Sea region, where a large portion of European wind energy is generated, is not among the best places for reliably producing wind energy due to variability in wind intensity. This once again highlights the gap in knowledge on where and how to develop the wind industry and how to prepare for issues such as variability that come part and parcel with this energy source.

Another major issue that has emerged in recent years is related to supply chain issues and inflation. According to Climate Change News, experts in the wind industry, such as Emil Damgaard Grann, head of global positioning at Ørsted, “Persistent inflation and rising interest rates have meant the cost of building new wind farms has spiraled.”

Swedish company Vattenfall estimates the costs of building an offshore wind farm have increased by up to 40% this year, making a planned 140-turbine offshore wind development in the North Sea unfeasible.

A view that was also echoed by the Wall Street Journal in an article that found that $30 billion in investment has been put on hold as at least 10 offshore wind projects in the US and Europe experience delays.

In fact, the WEF’s Fostering Effective Energy Transition 2023 report emphasizes the need for, “Government and business leaders must work together to find solutions to financing, regulatory and permitting issues [as] project delays could leave us even further from achieving what is required and undermine the affordability and sustainability of energy.”

Although it does seem that wind power is starting to turn the corner following the dip experienced in 2022 and 2023, the industry needs to overcome not only the political and economic hurdles but also logistical and social issues that will determine how fast it can continue to grow. Whether in the choice of locations to avoid the inherent variability of wind or in the ability to win over local communities, there are considerable headwinds lying in wait.