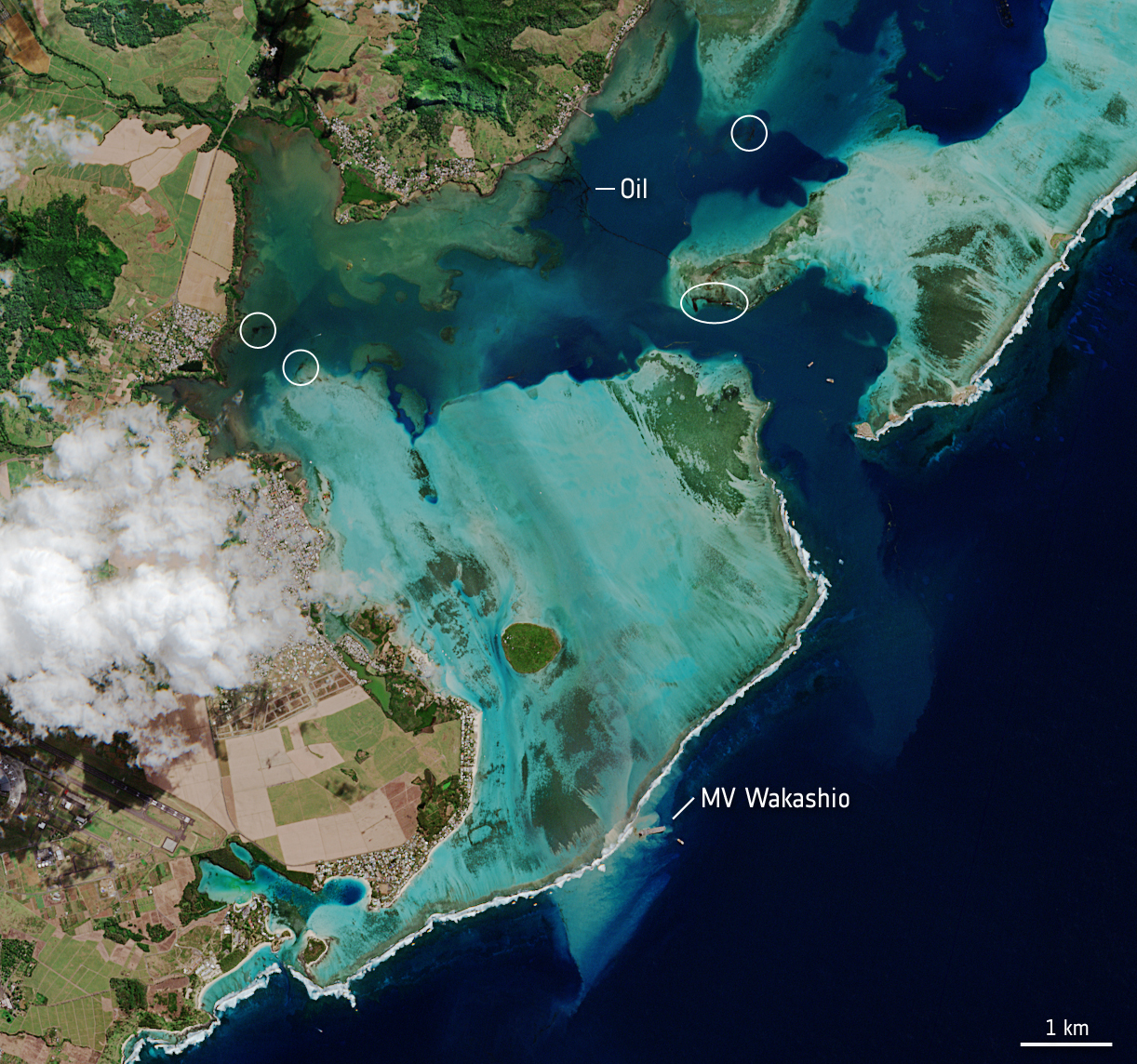

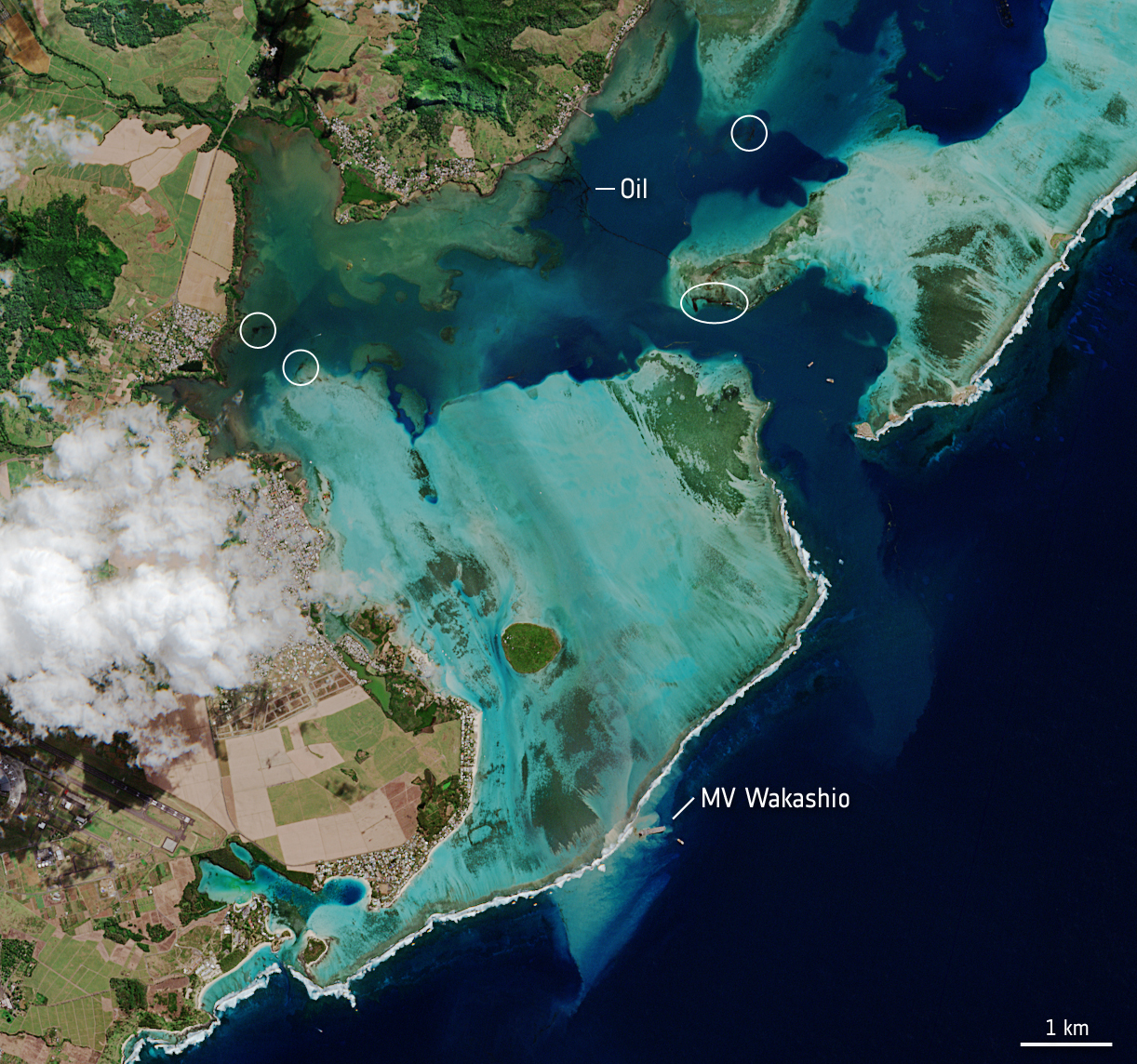

The bulk carrier, MV Wakashio, a 984-foot-long vessel sailing from China to Brazil ran aground off the southern coast of the island of Mauritius, near Pointe d’Esny, on 25 July 2020. The Japanese owned ship, sailing under a Panamanian flag of convenience, has since become the focus of international attention as a potential 4,000 tonnes of fuel and 200 tonnes of diesel were at risk of tainting the pristine blue waters of this tropical paradise with an ineffaceable black smudge. Yet another instance of marine shipping leading to oil spills.

Mauritian Government representatives have scrambled to contain the spill and called for international support. “This is the first time that we are faced with a catastrophe of this kind and we are insufficiently equipped to handle this problem,” explains Sudheer Maudhoo, Minister of Blue Economy, Marine Resources, Fisheries and Shipping. Similarly the environment minister, Kavydass Ramano, also stressed the risk of an unprecedented environmental crisis and the dire consequences that the spill could wreak on the island nation’s tourism and food security.

The Mauritian Prime Minister, Pravind Jugnauth, was forced to call a state of emergency and appeal for international help in dealing with the crisis. This led to France and Japan sending aid teams and the ship’s operator, Mitsui OSK Lines, and local volunteers placing containment booms around the Wakashio to hold back the spread of oil. By 13 August, 3,000 tonnes of fuel were offloaded from the Wakashio successfully just days before the ship split in two. Local authorities and those responsible for the collision are now left with the arduous task of dealing with over 1,000 tonnes of fuel that have spilt into the surrounding ocean, and the ship’s carcass.

Simulating the weathering and transport of the Mauritius oil spill

“An important part of dealing with the oil spill is understanding where it will move to” explains Giovanni Coppini, Director of Ocean Predictions and Applications division at CMCC and an expert in oil spill emergency management at sea and development of environmental and climate change ocean indicators. Using operational oceanography observations, modelling products and climate re-analyses his team has produced one of the first simulations of how the Wakashio spill will spread. “We use Copernicus Marine Service current forecasts and wind forecasts by the ECMWF, using these two ‘forcings’ to simulate the weathering and transport of oil at sea, after which we apply them to our own CMCC Global Oil Spill fate and Transport model to generate predictions” he explains. “We are looking to demonstrate the European Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service’s ability to provide sea current forecasting models that can be used to forecast oil spills on a global scale.”

This is not the first time that Coppini and the CMCC team have been involved in responding to marine environmental emergencies. He was previously head of a JCOMM Expert Team on Marine Environmental Emergencies Response (ETMEER) that sought to develop best practices and coordination in the field. Moreover, the CMCC team has provided oil spill forecasting, in collaboration with MONGOOS partners and REMPEC, in many other cases in the Mediterranean Sea including in mapping the oil spill caused by the collision between the Ro-Ro ship Ulysse and CSL Virginia on 7th October 2018 off the coast of Corsica.

On 21 August the forecast Bulletin on the Wakashio oil spill accident was published: “The oil spill trajectory and fate were simulated using the MEDSLIK-II oil spill model coupled with Copernicus Marine Service (CMEMS) oceanographic and ECMWF meteorological products.” However, due to the complexity of the spill scenario, which involves a reef and currents that are not covered by CMEMS Global currents fields, only wind forcing was used whereas simulations for areas outside the reef lagoon included current forcings. Comparing the forecast simulation reproducing the spill from 10-16 August against satellite imagery revealed that the MEDSLIK-II simulations were reasonable. Furthermore, the forecast is that the spill will remain as previously simulated and hence “close to the southern coastline of the embayment and in the Blue Bay.” The largest uncertainties about its development stem from fields inside the embayment and the spill rate from the Wakashio shipwreck.

Meteo France has also developed an initial model simulating the dispersion of oil in Mauritius based on their forecasting systems. However, “by drawing on our access to satellite images provided by Sentinel 1 and 2 (which are also part of Copernicus), MEDSLIK-II is the first to see how accurate these simulations are”, explains Coppini.

More shipping spills on the horizon

Unfortunately, the Wakashio is just one in a long history of marine oil spills. One of the first cases to grab significant attention involved the Liberian tanker Torrey Canyon. On 18 March 1967, the tanker struck rocks off the coast of Cornwall, England, pouring 120,000 tonnes of crude oil into the ocean and acting as a true wakeup call for the international community. In 2019 alone there are believed to have been at least 6 significant oil spills (7 tonnes or more) from shipping. On a positive note, the average number of significant spills per year in the 1970s was about 79, meaning that there has been almost a 90% decrease in these kinds of incidents.

However, as the recent example in Mauritius indicates, complacency is not an option. Furthermore, instances such as that of the compromised oil supertanker, the FSO Safer, off the coast of Yemen require urgent attention. The Safer has also been in the spotlight as it is at risk of spilling a million barrels of crude oil into the sea. This would amount to four times the amount of crude spilt in the Exxon Valdez disaster of 1989 and hence become one of the largest oil spills in human history. The UN reports that seawater is already seeping into the Safer and that if access to the tanker off the Yemen coast is not granted we could be faced with catastrophic consequences.

The Safer, built in Japan in the 1970s and now owned by the Yemeni government, has received no maintenance since 2015 when the Shiite Houthis succeeded in taking over the government in Sanaa. The ship has since become a pawn in a geopolitical conflict that sees the Houthi rebels resisting Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen. The tanker’s precarious situation is now facing increased scrutiny as people draw parallels with the recent explosion in Beirut, where tonnes of ammonium nitrate were left in unsafe storage due to issues with a shipping vessel, political turmoil and the government’s inability to address an impending crisis.

The #Beirut tragedy is a reminder that we must take action on all threats to human and ecological health. #Yemen https://t.co/tGtYpskRgJ

— Inger Andersen (@andersen_inger) August 8, 2020

“Time is running out for us to act in a coordinated manner to prevent a looming environmental, economic and humanitarian catastrophe,” explains Inger Andersen, Under-Secretary-General and Executive Director of the United Nations Environment Programme, further elaborating that access needs to be granted to the Safer to assess its condition and determine how its cargo can be safely off-loaded. Yemen’s information minister, Moammar al-Eryani, also warns that there could be a “human, economic and environmental catastrophe” if the Safer sinks or explodes.

The economic and environmental implications of marine shipping oil spills

Already, the question of who will pay for the Wakashio oil spill is surfacing. Typically ship owners are the ones to foot the bill and in this case the owners of the ship are Nagashiki Shipping, who are expected to bear the liability for damages.

Grounded Mauritius Ship Operator Apologises for Oil Leak

TOKYO — "We apologise profusely and deeply for the great trouble we have caused," Akihiko Ono, executive vice president of Mitsui OSK Lines said at a new conference in Tokyo.https://t.co/TtCPe6O0Ww pic.twitter.com/5p4YkW6V8e— Mauritius Island (@MauritiusGuide) August 9, 2020

Although the shipping company has not declared how much it expects the clean-up to cost there are precedents. In 1997 a Russian-flagged tanker sank in the sea of Japan, releasing over 6,000 tonnes of oil and eventually agreeing to pay damages up to 26.1 billion yen (246 million USD at current rates). According to Michio Aoki, an attorney specialising in marine accidents, payments will likely be capped at 2 billion to 7 billion yen for a ship of the Wakashio’s size, under a 1976 convention on liability for maritime claims, reports Nikkei Asian Review.

Aside from the economic reparations, there is also the irreversible damage that can be done to local biodiversity. “Thousands of species around the pristine lagoons … are at risk of drowning in a sea of pollution, with dire consequences for Mauritius’ economy, food security and health,” denounces Happy Khambule, senior climate and energy campaign manager at Greenpeace Africa.

Lorsque la biodiversité est en péril, il y a urgence d’agir. La France est là. Aux côtés du peuple mauricien. Vous pouvez compter sur notre soutien cher @PKJugnauth. Nous déployons dès à présent des équipes et du matériel depuis La Réunion. https://t.co/uxoNhAQWfS

— Emmanuel Macron (@EmmanuelMacron) August 8, 2020

How pervasive the consequences of the Wakashio spill in Mauritius will be is yet to be seen. According to a 2010 study, the effects of oil spills change according to a variety of factors including: “the physico-chemical parameters of the oil, the characteristics of the environment affected, and the physical, chemical, and biological processes occurring there, such as evaporation, dissolution, dispersion, emulsification, photo-oxidation, biodegradation, and sedimentation.” For example, black and sticky fuels are usually less toxic than light oils such as diesel but at the same time are harder to breakdown, last longer and smother life in the sea and on the coasts.

However, it goes without saying that oil spills pose a significant danger to fauna and flora and cause damage to marine and land ecosystems, as well as local livelihoods, which are already under increasing pressure due to climate change . Petroleum-related chemicals that are spilt are toxic, often carcinogenic or can be bioaccumulated in the tissues of marine organisms. Although these kinds of incidents should be avoided before they happen, science can offer a valuable tool for predicting the movement and pervasiveness of these spills and thus help contain the worst of their effects after they happen.