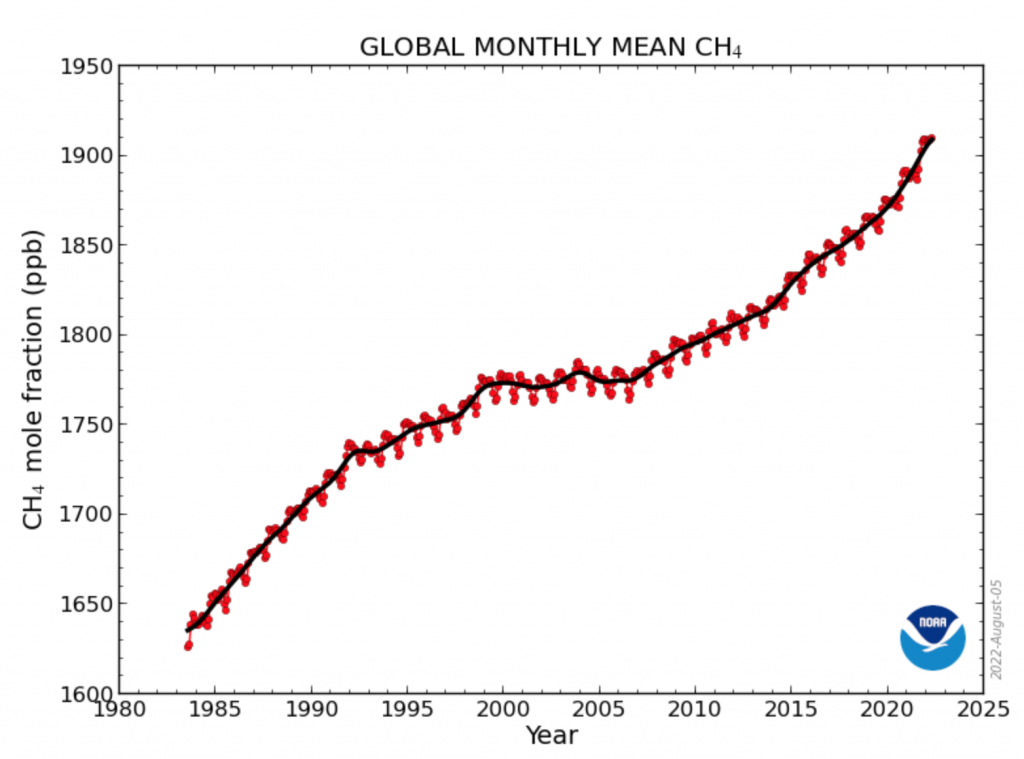

For two years running, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has reported record atmospheric methane concentrations in the atmosphere. In 2021, atmospheric methane was 150% higher than it was before the Industrial Revolution, proliferating faster than at any other time since record keeping began in the 1980s.

“It is shocking,” says Lindsay Xin Lan, a researcher based at NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado, when speaking to the Financial Times. “A lot of research, a lot of scientists, are trying to explain it.”

Even as carbon dioxide emissions decelerated during the pandemic-related lockdowns of 2020, atmospheric methane shot up. This is particularly alarming as methane is more than 25 times as potent as carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere.

On the other hand, once emitted, carbon dioxide remains in the atmosphere anywhere between 300 to 1,000 years, whereas methane typically dissipates within a decade. This means that tackling CO2 emissions today will have an effect relatively far into the future, whereas addressing methane will bring significant and almost immediate results.

The United Nations considers methane concentration reductions one of the fastest and most effective ways of reducing global warming, and in its 2021 Global Methane Assessment goes as far as outlining how a unified global approach using available technologies could bring down man-made methane emissions by 45% by 2030, avoiding 0.3C of warming by the 2040s.

Most countries recognised the urgency of the situation in 2021 at the COP26 where they agreed to slash methane emissions 30% by 2030 in the Global Methane Pledge. “If we do something about methane,” says Robert Kleinberg, an expert on energy policy at Columbia University, when talking to National Geographic, “temperature will increase more slowly than it otherwise would.”

So, if there is such widespread recognition of the issue, what is causing methane levels to continue to climb so drastically?

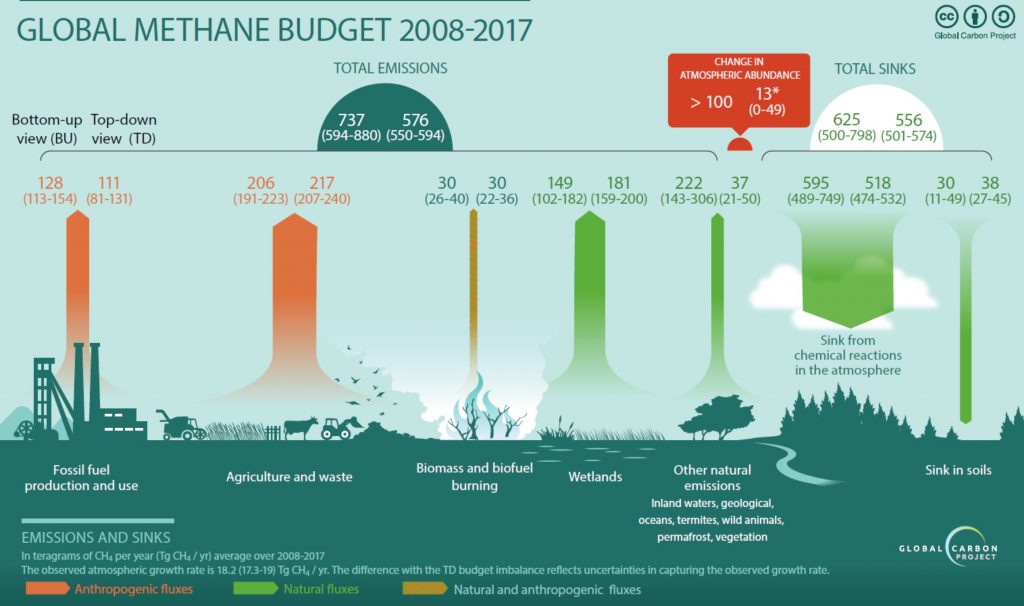

Research indicates that the recent surge has not been coming from human activity and the burning of fossil fuels – at least not directly. Instead, microbial sources have been identified as the culprits. This includes wetlands, cattle and landfills, which all produce “microbial” methane, whereby microbes break down carbon producing the greenhouse gas as a side product.

Although it is hard to get exact figures, as the origins of methane are not always easy to identify, new research indicates that 85% of the increase since 2007 is down to microbial sources.

Furthermore, as the planet continues to warm there is concern that these microbial sources will continue to emit more and more methane in a self-perpetuating vicious cycle. Researchers even fear that a tipping point may be reached in certain parts of the world, whereby large amounts of methane stored in natural reserves will be released as the planet continues to warm.

The dangers of methane

Yet the dangers of methane are not only limited to its impacts on planetary warming.

Methane is also one of the foremost sources of ground-level ozone, a dangerous air pollutant and greenhouse gas which causes around 1 million premature deaths every year. In fact, the link between methane, air pollution and health issues is one of the less considered dangers.

“Air pollution and climate change are intrinsically connected. They both affect human health and well-being,” explains RFF-CMCC European Institute on Economics and the Environment scientist Lara Aleluia Reis. “Although they have different spatial scales – climate change is a global problem and air pollution is a local one – both environmental issues are connected because they share certain emission sources.”

In the recent research paper co-authored by Reis, Internalizing health-economic impacts of air pollution into climate policy: a global modeling study, policy approaches that tackle both issues at the same time, and therefore maximize co-benefits, are called for. Reis argues that “integrating the health dimension in the policy design, has proven to be important. The health impact of policies should be central to decisions and not just an aftermath policy benefit.”

In this context, methane is also signaled as an important gas for tackling both long-term and short-term environmental problems. “Methane is both a powerful greenhouse gas and a precursor of ozone, which in turn provokes premature mortality. Therefore, reducing methane leads to benefits for both environmental problems,” explains Reis.

Where is the current methane spike coming from?

With such a wide body of research on the negative impacts of methane, why are levels continuing to rise so fast?

Numerous new research papers have been published on the causes of the methane spike including ones that look specifically at where anthropogenic emissions are coming from.

One such study, published in Science Advances, uses satellite imagery to identify methane emissions arising from landfills around the world. Analyzing images from Delhi and Mumbai in India, Lahore in Pakistan and Buenos Aires in Argentina researchers were able to pinpoint landfills in cities as the sources of high methane emissions.

“This is the first time that high-resolution satellite images have been used to observe landfills and calculate their methane emissions,” explains Joannes Maasakkers, lead author of the study and atmospheric scientist at the Netherlands Institute for Space Research, when talking to AP News.

Satellites were also used to locate another large methane leak, namely at an offshore platform in the Gulf of Mexico belonging to the Mexican oil company Pemex.

In exclusive data and interviews shared with Reuters, over a short period of time some 44,064 tons of methane were released into the atmosphere, equivalent to 3.7 million tons of CO2.

“It’s really alarming what is happening,” commented opposition Senator Xochitl Galvez when shown the data by Reuters. “Pemex should be stripped of its rights to operate it.”

Although it is normal for natural gas to come to the surface during oil extraction this is usually burnt off, or flared, so as to minimize environmental impacts. The fact that methane is being allowed to enter the atmosphere on this scale suggests that there are operating issues at the facility and also represents an environmental catastrophe.

Are we approaching a tipping point?

Yet the largest concern when it comes to methane remains tied to non-anthropogenic emissions and our inability to control them if they get out of hand. New research published in August reveals how a major reserve of seafloor methane off the coast of Africa was released into the atmosphere 125,000 years ago after a change in sea currents led to ocean warming of 6.8 degrees Celsius.

Methane (CH₄) is a potent greenhouse gas. Here are the newest observations just in… 📈

May 2022 – 1908.7 ppb

May 2021 – 1891.6 ppb+ Data (@NOAA_ESRL): https://t.co/PPWYaZVeSA

+ More info on trends: https://t.co/UIMDzbWQfS pic.twitter.com/MzWgf9OBPo— Zack Labe (@ZLabe) September 6, 2022

This raises the alarm of a similar event happening as temperatures continue to rise due to global warming, although scientists who reviewed the study agree that this remains an unlikely scenario.

However, what the study does indicate is that shallow deposits of frozen methane held in ocean sea floors may be more vulnerable to thawing than previously imagined. Whereas currently cold temperatures and high pressure lead to approximately one sixth of global methane sequestration, global warming could call this into question.

Although countries are trying to find ways of tackling the issue of methane emissions, research indicates that more needs to be done. The USA’s Inflation Reduction Act, the biggest climate bill in US history, is a case in point. Here methane takes an eminent role whereby a fee on emissions has been set of $900 per metric ton as of 2024, rising to $1,500 per ton by 2026.

However, the new law fails to look at the totality of methane emissions and only covers the oil and gas sectors, which make up approximately one-third of total emissions. For example, the agricultural sector and landfills don’t feature in the tax, leaving a gaping hole in the plan.

Similarly, the Global Methane Pledge agreed upon at COP26 fails to include the two largest global methane emitters, China and India.

“If you think of fossil fuel emissions as putting the world on a slow boil, methane is a blow torch that is cooking us today,” says Durwood Zaelke, president of the Institute for Governance & Sustainable Development, when talking to the Financial Times. “The fear is that this is a self-reinforcing feedback loop [. . . ] If we let the earth warm enough to start warming itself, we are going to lose this battle.”