On 11 December 1997, representatives from 160 nations gathered in Kyoto, Japan, for the Third Conference of the Parties (COP) to sign a historic agreement: the Kyoto Protocol. In an unprecedented moment of international consensus making, the Protocol strove to address global warming by cutting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 38 industrialized countries by 5.2% between 2008 and 2012 compared to the levels registered in 1990.

For the first time ever, legally binding targets and commitments were set and key economic players such as Japan, the US and the European Union pledged to cut their emissions by 7%, 8%, and 9% respectively.

Then US President Bill Clinton heralded the Agreement as “environmentally strong and economically sound” and for many both at the time and still today the Kyoto Protocol represented a shedwater moment in the struggle to address man’s impact on the Earth’s climate.

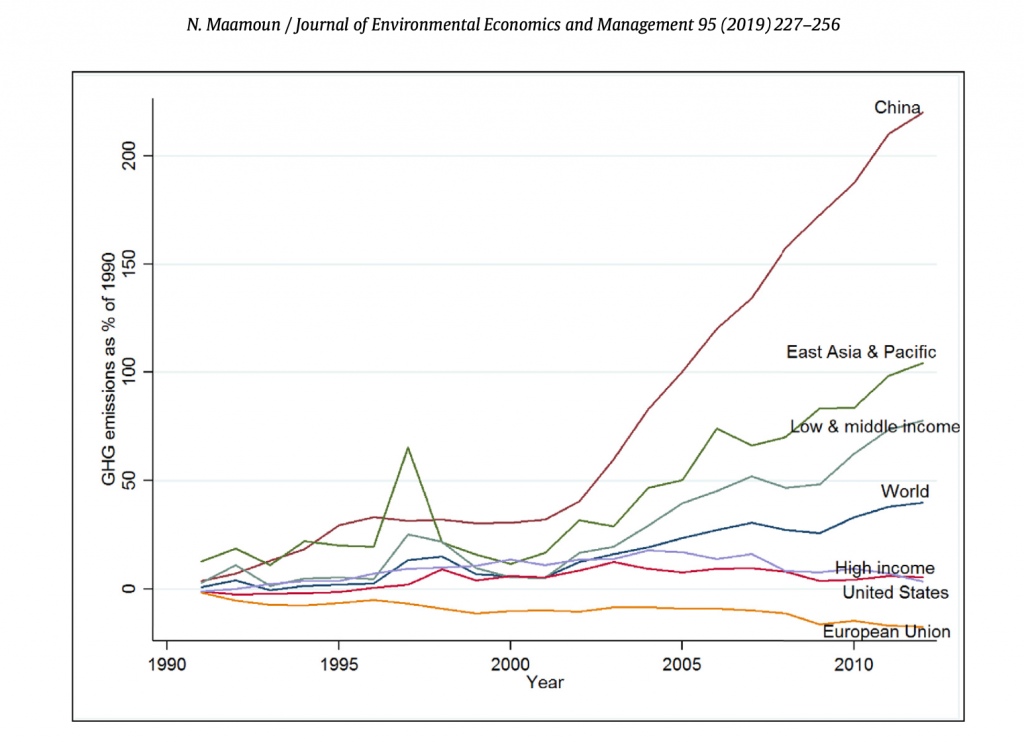

However, it soon became evident that the Protocol was going to do little but paper over the cracks when it came to addressing global emissions. First and foremost, the reduction commitments would come exclusively from those nations that were historically responsible for emissions following the UNFCCC’s common but differentiated responsibility principle that saw developing countries exempt from any emission reduction commitments.

This paved the way for significant problems in the scope and effectiveness of the Protocol. Although in 1997, the US and EU were the world’s largest emitters, by 2006 China surpassed the United States in annual emissions, and India’s emissions are currently almost equal to those of the EU.

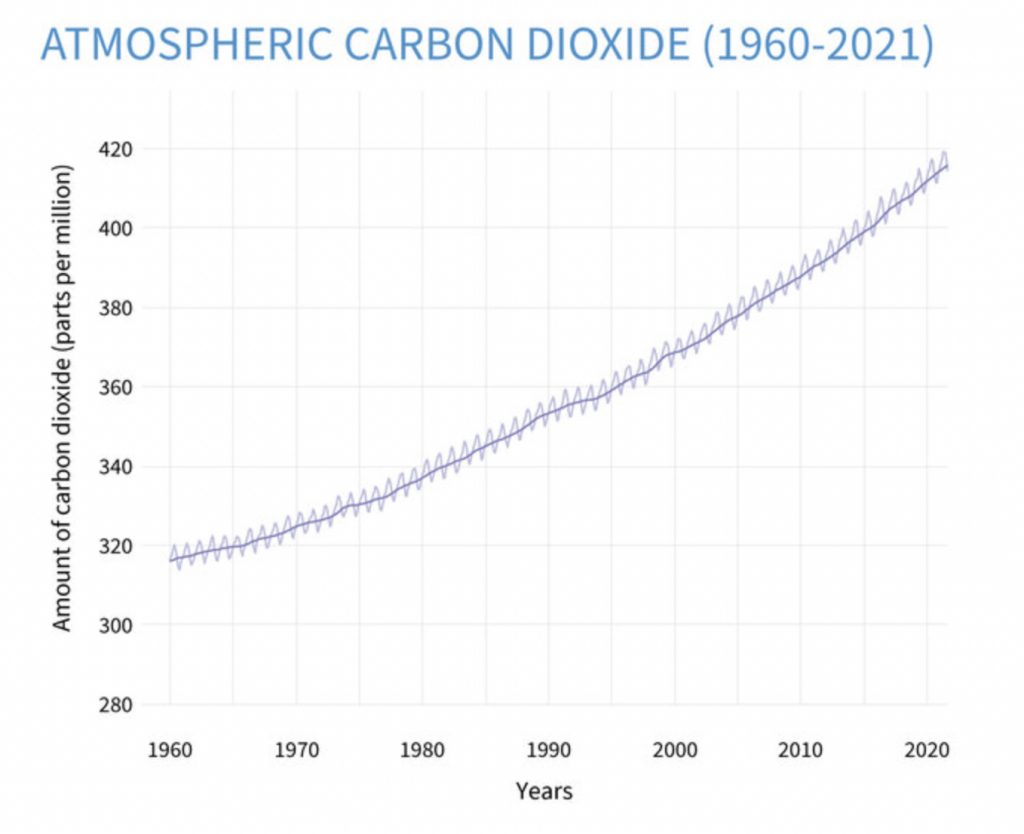

Even more damningly, by 2012, the year after the first commitment period, global emissions had risen 44% from 1997 levels, driven predominantly by emissions growth in developing nations. The Kyoto Protocol had failed to stem the flow of global emissions.

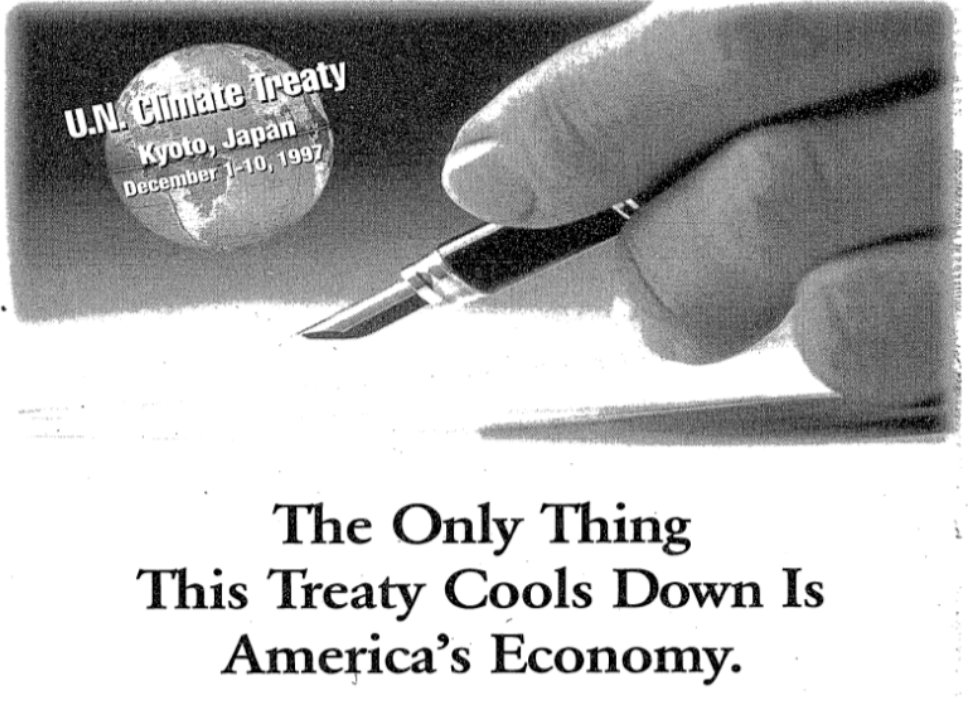

Still further, the Kyoto Protocol failed to equate emissions reductions with economic opportunity and some countries grew to view mitigation as a costly punishment. Following this line of reasoning the US Senate refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol, citing potential damage to the US economy as their motive, setting a precedent for countries such as Canada and Japan to pull out of the deal without penalty in 2011 and providing a serious setback on the agreements effectiveness right from the get-go. What chance of success did it have if the world’s largest emitter would not adhere to its commitments?

Achieving its goals

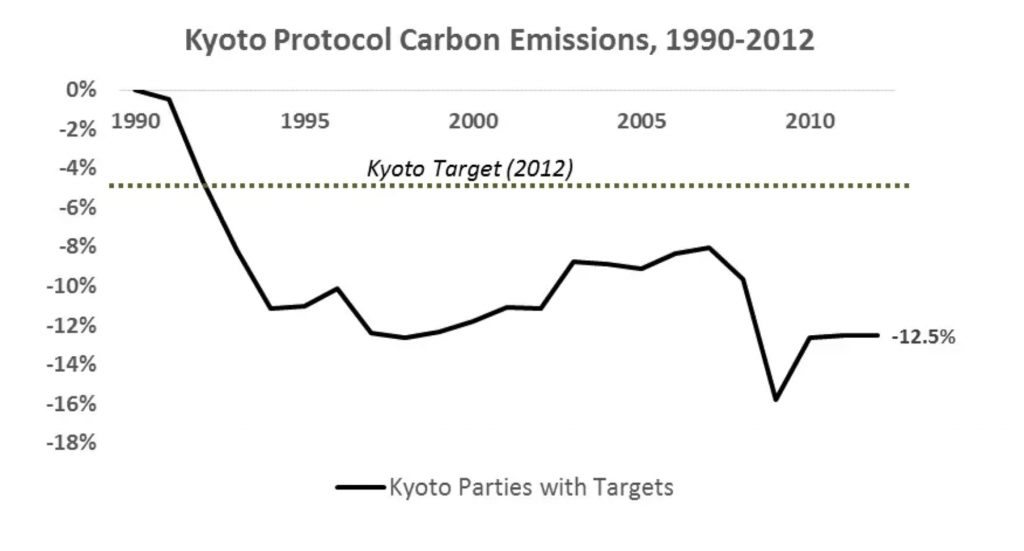

Analyzing the effectiveness of the Kyoto Protocol also involves understanding what its goals were. On paper the agreement actually achieved its overall goals. Aggregate emissions reductions over the first commitment period are generally agreed to be between 7% and 12.5%, therefore comfortably exceeding the 5.2% pledge.

However, digging below the surface of these numbers it is clear that the overall picture is a little more complex than this. A significant amount of the reductions came from former Soviet Union states that used emission benchmarks from the USSR.

The issue with USSR countries is that the carbon credits assigned to them were larger than their expected business as usual emissions levels – what is known as ‘hot-air’ – which allowed them to sell the extra assigned amounts, without actually having to perform any reduction in emissions levels. This not only meant that they had no incentives to reduce emissions but also ends up inflating any analysis of the gains made under the Protocol if you include the former Soviet countries.

In fact, the ultimate criticism of the Kyoto protocol is that global emissions are still increasing relative to 1990 levels to this day and much of this increase is driven by the very countries that were excluded from reduction targets under the Protocol. However, this would be evaluating its success against an outcome that it never sought to reach. Ultimately, the Protocol’s goal was not to reduce global emissions but to reduce them in industrialized countries and lay the groundwork for future negotiations in which developing countries would be included into the process.

“Even if it didn’t really lead to a significant reduction in emissions, the Kyoto Protocol was an important step towards a carbon neutral world, particularly from a political standpoint.” explains international climate negotiation expert at the University of Bern, Ralph Winkler, whose research on the Kyoto Protocol indicates that not only did it lead to no significant benefits in terms of emissions but that in some cases it may even have hindered emission reduction efforts in countries that had set Kyoto targets.

“The Kyoto Protocol showed that it was possible to strike a global agreement on climate and that the world community could build a consensus on climate goals and even fulfill them,” continues Winkler in an exclusive interview for Foresight where he discusses the Kyoto Protocol’s legacy and the future of international climate negotiations in today’s fast changing world.

A world without the Kyoto Protocol

Yet not all research agrees with the idea that a world without the Kyoto Protocol would have seen less emissions. “To examine the protocol’s effectiveness more fairly it would be better to compare the GHG emissions of the industrialized countries with the expected business as usual emissions that would have occurred in the absence of the protocol,” says Nada Maamoun, expert in global climate policy at the University of Hamburg who discusses the issue in depth when talking to Climate Foresight about the true merits of the Kyoto Protocol and the issues associated with these kinds of comparative studies. .

Maamoun’s paper, The Kyoto protocol: Empirical evidence of a hidden success, concludes that in fact the Protocol was successful at least in preventing a worse-off situation, where industrialized countries might have had higher emission levels had they not ratified the agreement echoing the findings of other researchers such as Nicole Grunewald. “The tricky point here is we don’t have this counterfactual: we don’t have the business as usual scenario in real life”, says Maamoun.

In fact, although Winkler uses a similar method to Maamoun his conclusions are significantly different. “Although the aggregate target was achieved, it would seem that this was more by coincidence and that the targets were not, at least on aggregate, ambitious enough. Even papers that see an emissions reduction effect due to the Kyoto Protocol see relatively small gains. The reduction goals were simply too conservative,” says Winkler in his paper, The case of the Kyoto Protocol.

Notwithstanding the discrepancies in research on whether Annex B countries actually emitted less in light of their Kyoto Protocol commitments, what most researchers do agree upon is that the true legacy lies in how it paved the way for future climate negotiations and revealed the loopholes that can emerge in these processes, therefore contributing fundamental lessons to future negotiations.

Kyoto’s legacy lives on

“We have to look at the impact as more than just what it did for greenhouse gas emissions. We need to consider what would have happened if the Protocol hadn’t been in place and also its role in laying the groundwork for future agreements,” says Maamoun.

The Kyoto Protocol was directly responsible for much of the architecture for later climate negotiations including the Paris Agreement and its legacy includes mechanisms such as the adaptation fund, carbon markets, and other tools designed to raise ambition and speed up global decarbonization.

Furthermore, the Kyoto Protocol shows that unilateral and broad consensus agreements may not always be the most effective way of tackling climate issues. According to Winkler, combining broad consensus approaches under the UNFCCC with smaller agreements between countries that are on similar trajectories can provide more ambitious and effective agreements.

“You can have these kind of consensus treaties that the UN facilitates, like the Paris Agreement, and on top of that, you could have additional agreements with smaller groups of countries,” says Winkler, whose recent research focuses on this interplay, as well as the interaction between domestic and international environmental policymaking.

Smaller coalitions of countries would also make it easier to impose sanctions and more forceful disincentives for failure to meet targets. In fact, a common criticism of today’s Paris Agreement has carried on from the Kyoto Protocol: that being a lack of any significant kind of punishment or sanctioning mechanism when countries do not stick to their climate pledges.

In this context unilateral or even bilateral trade moves could provide strong incentives for change. For example, the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism will impose a carbon tax on a select number of commodities coming from abroad based on their environmental performance.

Although these alternatives can provide extra fodder, what is also clear is that, twenty-five years on from the Protocol, the UN process continues to be an essential part of how we tackle climate change and has undoubtedly benefited from over two decades of successes and, inevitably, failures that started with the Kyoto Protocol.

“It is not a matter of choosing between one or the other. The UNFCCC endeavor can provide a good basic framework on which to build, but it’s also clear that this alone does not necessarily bring the changes we need,” says Winkler.

Cover Picture: UNFCCC-COP3 Gavel “Used for Adoption of the Kyoto Protocol COP3 President, Minister Hiroshi Ohki Kyoto International Conference Hall. December 11, 1997”

Source: Jason Riedy on Flickr – Creative Commons – https://flickr.com/photos/66142667@N00/7029228521