Studies indicate that man-made climate change leads to increased probability of heatwaves that put our environment under considerable stress. In turn these heatwaves contribute to widespread disruptions and natural disasters such as the current wildfires ravaging the Arctic. According to Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS), over June and July more than 140 megatons of carbon went up in smoke, equal to the total annual emissions of Belgium. An environmental crisis that must be factored into plans for remaining well below the 2ºC mark, and hence building a low carbon future.

The impact of the #Siberia #wildfires on #AirQuality (and probably on climatic processes) is mind boggling…

These are forecasts by our @CopernicusECMWF Atmosphere Service colleagues for Sunday

Left: PM 2.5

Right: Nitrogen dioxide

Values are way off scale (scale stops at 100!) pic.twitter.com/dvbybeKyFL— Copernicus EMS (@CopernicusEMS) August 9, 2019

Anthropogenic climate change leads to record breaking heatwaves

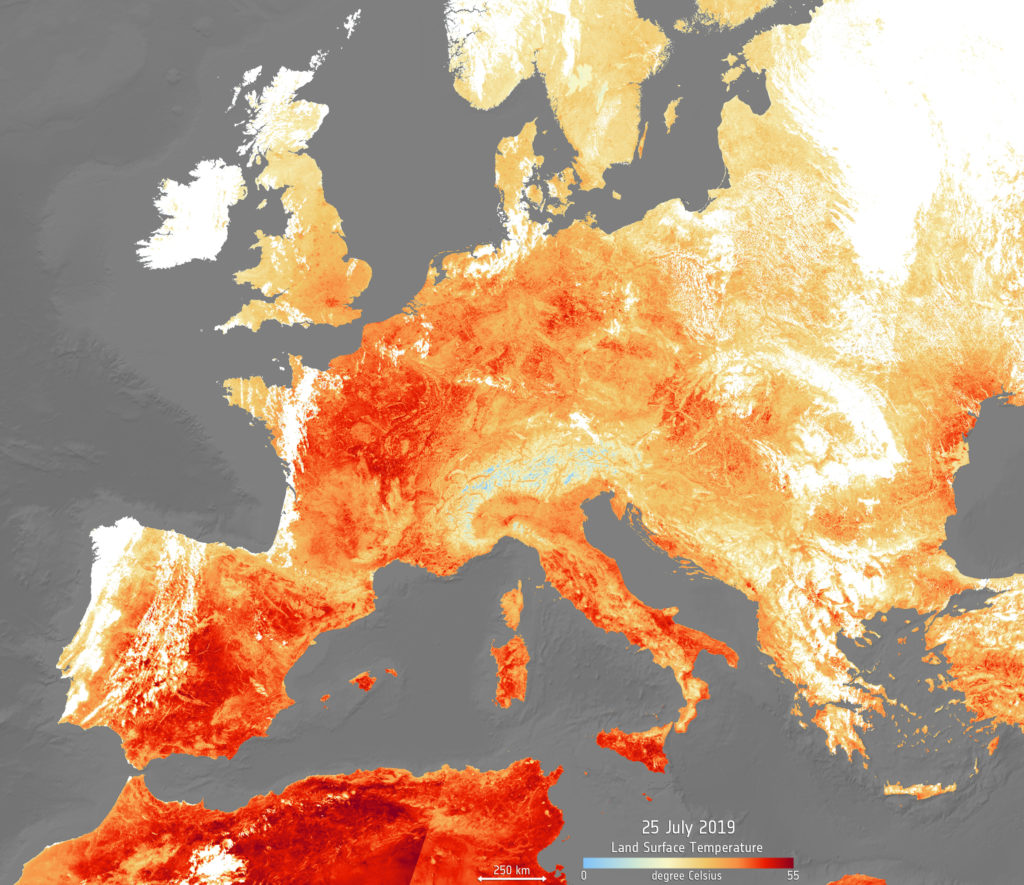

The WMO reports that July ended as the hottest month in recorded history. A finding that is particularly worrisome as 2019 is not an “El Niño” year. Instead, scientists indicate that the heat has been driven to a large extent by carbon emissions from car exhausts, power plant chimneys, burning forests and other human sources.

According to Johannes Cullmann, Director of WMO’s Climate and Water Department, “Such intense and widespread heatwaves carry the signature of man-made climate change. This is consistent with the scientific finding showing evidence of more frequent, drawn out and intense heat events as greenhouse gas concentrations lead to a rise in global temperatures.”

Human-influenced climate change is likely to have added 1.5-3ºC to the extreme temperatures recorded during Europe’s July 2019, according to a report by World Weather Attribution. WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas declared that: “July has re-written climate history, with dozens of new temperature records at local, national and global level […] Unprecedented wildfires raged in the Arctic for the second consecutive month, devastating once pristine forests which used to absorb carbon dioxide and instead turning them into fiery sources of greenhouse gases.”

Arctic forests are burning

Extremely dry ground and hotter than average temperatures (exceeding 30ºC), combined with heat lightning and strong winds, have contributed to fires spreading aggressively throughout the Arctic. One of the most affected countries is Russia, with large areas of Siberia going up in smoke. In Siberia alone, average temperatures were up to 8ºC above long-term averages and even reached all-time records, according to data from Russia’s state meteorological agency.

This led to over 3 million hectares of land in the centre and east of the country burning by the 31st of July, according to Russia’s federal forestry agency.

What is more, many of the wildfires are burning in extremely remote and hard to access areas, thus making intervention difficult and costly. This has led to criticism of Russian authorities that only decide to intervene if the estimated damage exceeds the cost of intervention, raising the question: how do we calculate wildfire damages? Is it just the damage that they can bring to populated areas or should we also consider environmental damages including effects on flora, fauna and the harmful emissions they release into the atmosphere?

Although the most alarming images and stories come from Siberia, wildfires aren’t just burning through Russia. Fires are raging throughout the Arctic circle, involving eight different countries. For example, in Alaska over 400 fires have been reported with climatologist Rick Thoman estimating the total area burned in the state this season (as of the 31st of July) at 2.06 million acres.

Smoke from the big northeast Interior Alaska #wildfires has moved across the Brooks Range and onto the North Slope. @BLM_AFS estimates total area burned in Alaska this season as of Wednesday morning at 2.06 million acres (832k ha). #akwx @Climatologist49 @vennkoenig @CinderBDT907 pic.twitter.com/SQY65lLJFf

— Rick Thoman (@AlaskaWx) July 25, 2019

A cloud of soot and CO2

Although summer fires in the Arctic are common, this year they have been far more pervasive than usual. According to Greenpeace, almost 12m hectares of forest burnt in 2019 alone.

Releasing a staggering amount of CO2: combined between June and July, more than 140 megatons of carbon dioxide, according to CAMS Senior Scientist and wildfires expert, Mark Parrington’s latest analysis. To put that into perspective this amounts to the same amount of carbon emitted by Belgium over the entirety of 2018 or as much carbon dioxide into the air as emitted by 36 million cars in a year.

“It is unusual to see fires of this scale and duration at such high latitudes in June,” claims Parrington. “But temperatures in the Arctic have been increasing at a much faster rate than the global average, and warmer conditions encourage fires to grow and persist once they have been ignited.”

In terms of emissions, Thomas Smith, an environmental geographer at the London School of Economics, states that “The amount of [carbon dioxide] emitted from Arctic circle fires in June 2019 is larger than all of the CO2 released from Arctic circle fires in the same month from 2010 through to 2018 put together.”

To make matters worse, environmental groups are also pointing to the fact that the carbon dioxide, smoke and soot released by these fires will contribute to accelerating temperature increases that are already contributing to huge losses of permafrost in the Arctic. According to Nasa scientists, the soot released from fires absorbs sunlight and warms the atmosphere. When this soot falls on ice or snow, it leads to more heat being trapped and hence accelerating melting processes.

Wildfires in perspective

Once fires start it is extremely hard to stop them, particularly in such remote areas. The recent wildfires and their massive CO2 emissions mean that it will be important to take them into consideration when implementing measures for reaching greenhouse gas reduction targets accorded with the Paris climate agreement. If we are to keep global temperatures well below the 2ºC mark understanding how extreme wildfires impact our overall greenhouse gas emissions enables planners to decide where to cut emissions elsewhere.

Furthermore, strong policies must be implemented to safeguard large areas of carbon-storing forests, so that they do not burn and are not turned into lower-carbon grasslands.

However, it is also important to put fires into context when talking about their CO2 emissions. Although they are high CO2 emitters their total contribution when compared to burning fossil fuels are minimal. Policy should continue to focus on a low-carbon economy with the added burden of offsetting CO2 emissions derived from wildfires.

According to Scott Denning, an atmospheric scientist at Colorado State University: “Without very strong climate policy, industrial emissions are likely to triple in this century. Against that backdrop, the climate effects of increased wildfires are smaller than the error bars in the climate effects of all that coal, oil, and gas.”