Throughout history, the sea has always been a source of risk and reward. A dual relationship that continues to this day, with coastal communities among the most vulnerable to climate change impacts – such as depleted resources, more extreme weather and sea level rise – whilst still relying on the sea for their wellbeing and livelihoods.

The vital role of oceans not only as a source of sustenance for countless communities, but also as the holder of immeasurable opportunities for sustainable development, has been widely recognised with the United Nations labeling the decade leading up to 2030 The Ocean Decade.

Global oceans are increasingly described as fundamental players in the fight against climate change by researchers and policymakers alike, due to their role as the largest carbon sink on the planet.

Protecting and maximizing the potential of our oceans involves approving legislation that regulates their management and promoting transformative ocean science solutions that can ensure sustainable development which revolves around seven key principles: a clean, healthy and resilient, productive, predicted, safe, accessible, and inspiring ocean.

Protecting the high seas

One vital component to protecting the ocean involves putting in place legislation that regulates the management of all those marine areas that lie outside of territorial waters and the jurisdiction of individual nations.

There were high hopes that a step in that direction would be taken during the recent negotiations at the UN Intergovernmental Conference on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) which took place in New York between the 7th and the 18th of March. Observers hoped that the conference would produce a final treaty for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity beyond territorial waters.

Official @EU_Commission commitment to the #HighSeasTreaty for #BBNJ being finalised in 2022! Thanks to all involved. @EU_ENV @VSinkevicius https://t.co/yG71snbC4P @IUCNBrussels @HighSeasAllianc @4kgjerde @IUCN_Med @DeepSeaConserve @DeepStewardship @O_Poivre_dArvor

— IUCN Global Marine and Polar Programme (@IucnOcean) March 23, 2022

However, UN Member States were unable to reach an agreement that could protect the high seas from exploitation, leading scientists, environmentalists and conservation organizations to blame Member States for “dragging their feet”.

In the lead up to the talks Peggy Kalas, coordinator at High Seas Alliance, commented that: “After decades of negotiations and planning, the world has a once-in-a-generation chance to build meaningful protections for an environment that supports life, as we know it.”

“It’s extremely important it happens now,” echoed Professor Alex Rogers, science director of Rev Ocean, when talking to The Guardian. “We’ve continued to see the industrialisation of areas beyond national boundaries, including distant-water fishing and potentially deep-sea mining.”

High seas cover nearly half of the world’s surface and most of these lie outside of exclusive economic zones controlled by individual states. Of the seas remaining outside of territorial limits, only 1.2% are currently protected by a loose patchwork of disjointed rules that are unable to stop the onslaught for resources.

From climate change and pollution to fishing, and deep-sea mining the high seas are increasingly exposed to exploitation.

“At the moment, there is a governance vacuum in the high seas, and for the ocean and developing countries, the status quo simply isn’t an option,” explains Dr. Essam Mohammed, Director General and representative for the State of Eritrea in the World Fish.

Some of the main threats to the high seas are given by technological advancements that allow for distant fleet fishing and other activities in international waters that threaten both the ecosystem balance and coastal communities.

I recently attended the Intergovernmental Conference for #BBNJ and urge & support the commitments of the @UN for a #HighSeasTreaty to ensure the safety & security of our #ocean and vulnerable #coastal communities.

Read our press release 👉 https://t.co/eRrz5OuWkd #AquaticFoods pic.twitter.com/mRlxM4hfAX

— Essam Yassin Mohammed (@EYMohammed) March 21, 2022

Although the high seas were once considered of little interest – economically, politically and from a research perspective – they are now a contested arena for resource grabbing. At the same time, research on these areas has also caught up, revealing that they support a strong marine ecology that provides a fundamental role in the global food supply, terrestrial ecology, and the planet’s climate system.

Despite discussions around marine protected areas in the high seas starting over two decades ago, observers have been left feeling frustrated at the lack of progress whereby there is still no treaty protecting international waters.

The blue economy

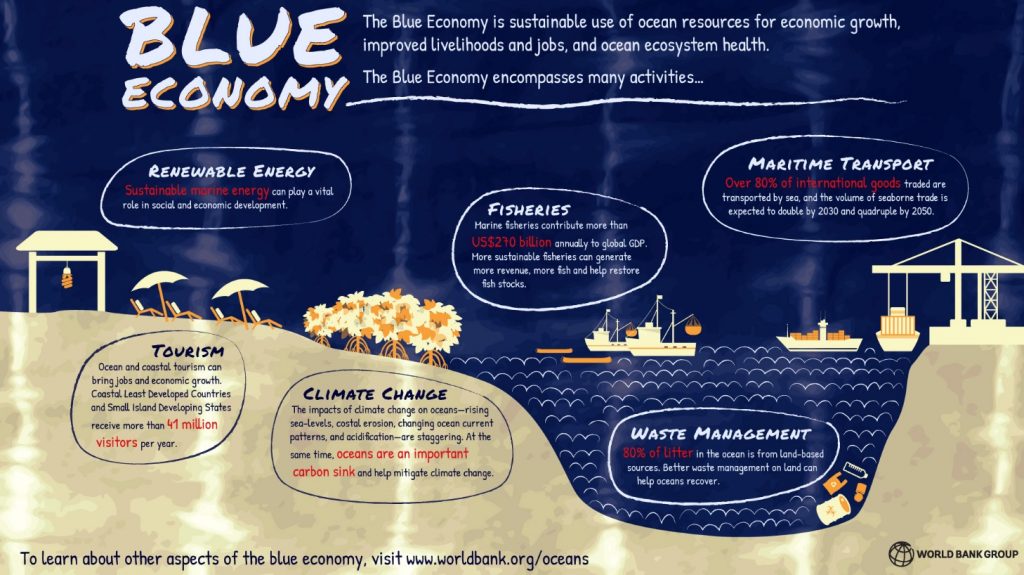

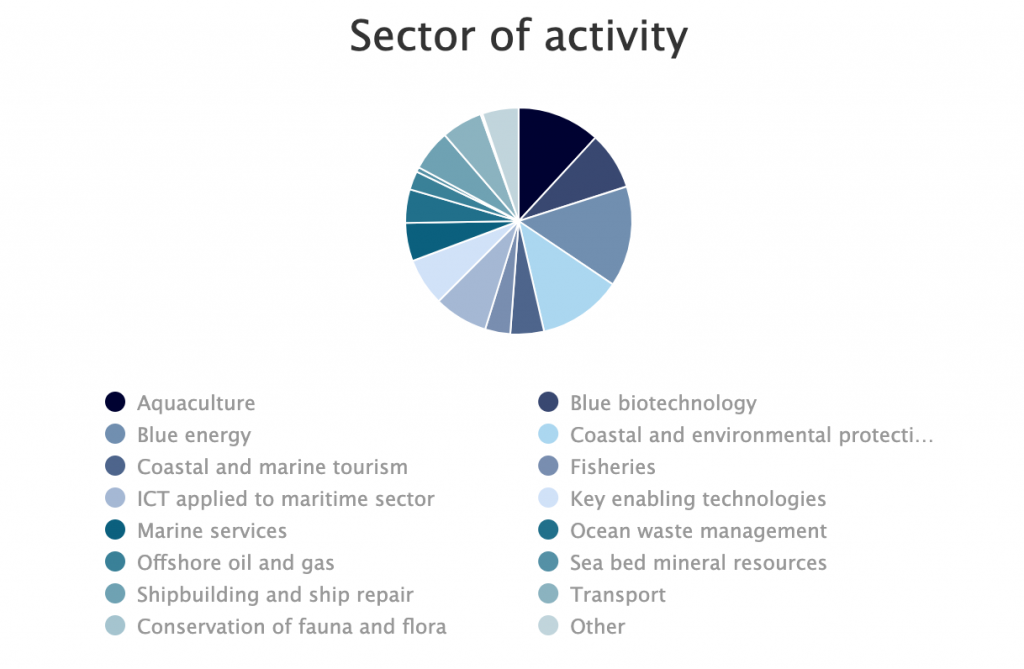

A key development has been the emergence of the blue economy concept, which the European Investment Bank Group defines as: “all economic sectors that have a direct or indirect link to the oceans, such as marine energy, coastal tourism and marine biotechnology.”

However, the blue economy doesn’t just see the world’s oceans as a valuable stock of resources, it also ties this idea to the “sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and jobs while preserving the health of the ocean ecosystem.”

Furthermore, global oceans are not only valuable for their resources but also due to their role as the largest carbon sink on the planet. A characteristic which, somewhat ironically, also makes them particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, whereby absorbing carbon increases ocean acidification and hence upsetting the ecosystem balance.

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report (AR6) reveals that the ocean is now warmer, more acidic, and less productive. Furthermore, melting glaciers and ice sheets are causing sea levels to rise, and coastal extreme events are becoming more severe.

The awareness of both the fragility of the ocean to overexploitation and the impacts of climate change, as well as an understanding of its great potential, has motivated legislators to promote initiatives that can help foster and grow the blue economy in a sustainable fashion.

At the BlueInvest Days 2022 in Brussels, Commissioner Virginius Sinkevičius and European Investment Fund (EIF) Deputy Chief Executive, Roger Havenith announced that they would mobilize an additional €500 million in EU funds for the blue economy.

This includes the BlueInvest platform and accelerator that fosters innovation and investment in sustainable technologies for the blue economy. Here SMEs can find funds and assistance in scaling up their businesses which include a wide variety of inspiring projects in areas such as: bio tech microalgae, excess renewable energy storage and salt water aquaponics farms.

The UN Ocean and Our Ocean conferences alone have collected around 1,000 measurable and financial commitments since 2017, and the EIB, as the EU climate bank, has invested greatly in developing a sustainable blue economy and supporting initiatives that reduce pollution and preserve the ocean and its marine biodiversity and ecosystem.

An approach that will continue into the future as the EU is linking its green recovery to the blue economy.

In May 2021 the Commission highlighted the opportunities presented by the blue economy and European Maritime Day 2022, on May 20th in Ravenna, Italy, will see high level speakers, leaders and a variety of stakeholders and experts showcasing key actions in the transition to healthy and clean oceans.

European Commissioner for Environment, Oceans and Fisheries Virginijus Sinkevičius comments on the EIB website: “There can be no Green Deal without a sustainable blue economy. Oceans are an incredible resource of renewable energy, food and innovative medicines and solutions, and host many economic activities constituting the blue economy. But our seas and oceans are also fragile ecosystems that need our protection. To achieve a climate-neutral, circular and clean blue economy in the European Union, we need to channel finance so that the projects contributing to the Green Deal can take off the ground. This is what our partnership with the EIB group will contribute to do.”