“The new climate war is a war not of our own choosing but one where powerful vested interests have been curtailing our ability and that of our policymakers to address the climate crisis in an effective way,” states Michael E. Mann, who firmly believes that climate policy is the key to addressing climate change and enacting significant change.

With 70% of all global CO2 emissions coming from just one hundred companies Mann posits that personal choices aimed at reducing our environmental footprint, although important, cannot act as a substitute for policy actions.

Climate policy provides the incentives and disincentives necessary to shift away from fossil fuels. Measures such as putting a price on carbon, providing subsidies for new and cleaner technologies that would otherwise struggle to breakthrough and blocking new fossil fuel infrastructure can be achieved mainly through policy measures.

Encouragingly the G7 nations’ recent meeting in Cornwall, UK, between Friday 11 and Sunday 13 June, saw climate issues continue to top the priority list (alongside the ongoing health crisis of course).

Leaders in Cornwall renewed their 2009 pledge to step up action and raise 100bn USD per annum to help poorer nations cut emissions and avoid getting locked into a fossil fuel driven development model.

We reaffirm the collective developed countries goal to jointly mobilise $100bn/year from public and private sources, through to 2025.

G7 Cornwall final statement.

Furthermore, they committed to a “green revolution” that seeks to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5C, achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 – including halving emissions by 2030 – and protecting at least 30% of land and oceans by 2030.

So how will these objectives be achieved? Research published in Nature Climate Change, indicates that the short and long-term impact of climate legislation has been significant bolstering the idea that demanding more of policymakers could be the secret to success.

G7 climate laws

According to research in 2020 climate laws in 2016 were associated with an annual reduction in global CO2 emissions of 5.9 GtCO2, which, for reference, amounts to more than the US CO2 output on that same year. Furthermore, total CO2 emissions savings from 1999 to 2016 amount to 38 GtCO2, or one year’s worth of global CO2 output.

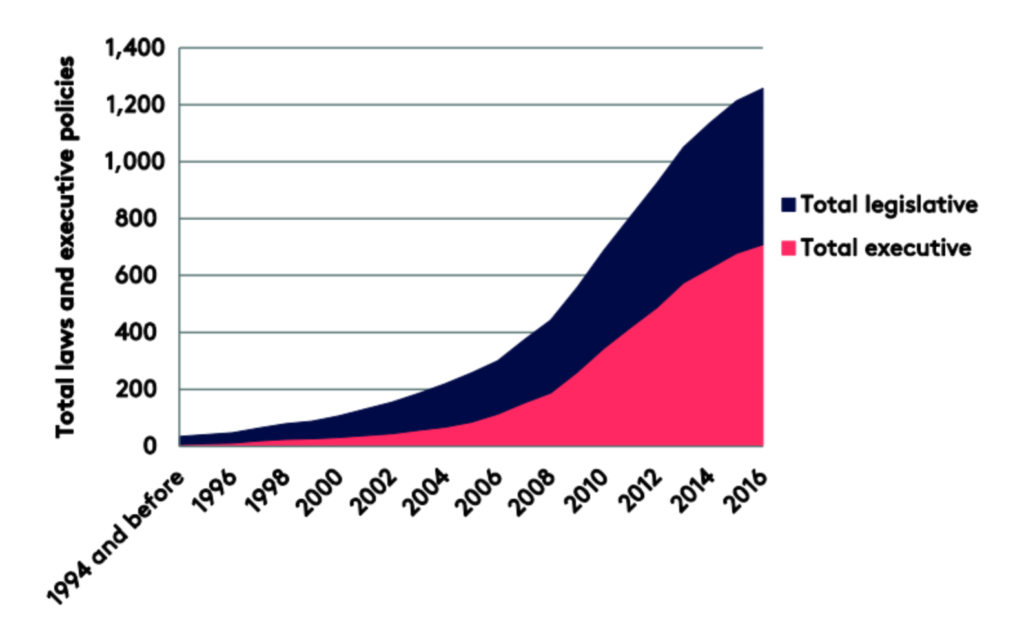

The research stipulates that there are over 1,800 climate laws worldwide and that each new law in the period between 1999 and 2016 “reduced annual CO2 emissions per unit of gross domestic product by 0.78% nationally in the short term (during the first three years) and by 1.79% in the long term (beyond three years).”

In the 20 years since the Kyoto Protocol this amounts to a 20-fold increase and indicates that although climate laws are effective from the get-go they tend to reach their full potential over time.

What is more, when applied to the G7 nations, the effects of climate laws are also marked. According to research conducted by Carbon Brief, the G7 group of major economies cut their collective carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by 1.3bn tonnes (GtCO2) in 2019 and that “CO2 emissions from the G7 countries in 2019 were 12% lower than they would have been, if no climate laws had been put into place.”

This is significant as it adds fuel to the premise that policy is central to climate change mitigation and that in fact climate laws implemented by the G7 nations have played a decisive role in the peaking of emissions.

Although socioeconomic factors certainly also play a role, and these are recognised in the research, overall results draw a picture where countries with the most successful climate climate legislation have bent the emissions curve by at least 15% and sometimes over 20%.

Encouragingly, it isn’t just G7 countries implementing climate laws. All Paris Agreement signatories or ratifiers to date have implemented at least one law addressing climate change or the transition to a low-carbon economy.

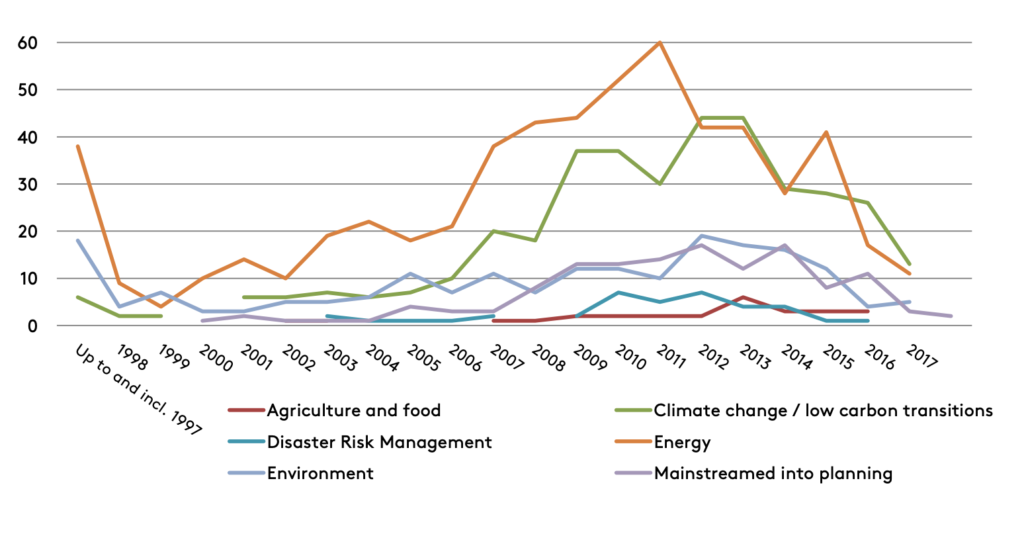

Furthermore, whereas “around a quarter of all the laws and policies are explicitly framed as climate change mitigation or adaptation laws, or as laws that target the reduction of greenhouse gases, other laws and policies integrate climate change considerations into laws that are focused on specific sectors or activities such as energy, forestry or transport.”

Institute on Climate Change and the

Environment and Sabin Center for Climate

Change Law (2018).

Developing countries

Central to the concerns of G7 countries is not only their own emissions but also the role they have to play, as wealthy countries that achieved their wealth with a fossil fueled development curve, in assisting developing countries.

At the G7 meeting in Cornwallclimate discussions put a lot of focus on providing cheap financing for building green energy infrastructure in developing countries.This is to ensure that they don’t build fossil fuel driven energy grids.

“We have to make sure the developing world skips this fossil fuel phase and doesn’t make the same mistakes we made. We have a responsibility to provide the resources to make sure that they can meet the needs of their people without sacrificing the health of our planet by adding to the climate crisis. Provide financing and funds such as the 100bn dollars agrred by the G7 is a good start and part of our moral obligation to provide what is necessary,” outlines Mann.

“If we become convinveed that it is too late to do something then we go down the path of disengagement. We have to help people through that phase and awaken from that spell,” continues Mann.

Encouragingly the science tells us that it is not too late to prevent the worst impacts of climate change. However, we have to act now and reduce carbon emission globally by a factor of two within the next decade if we are to avert over 1.5C increase. For this to happen policy will be a major player.