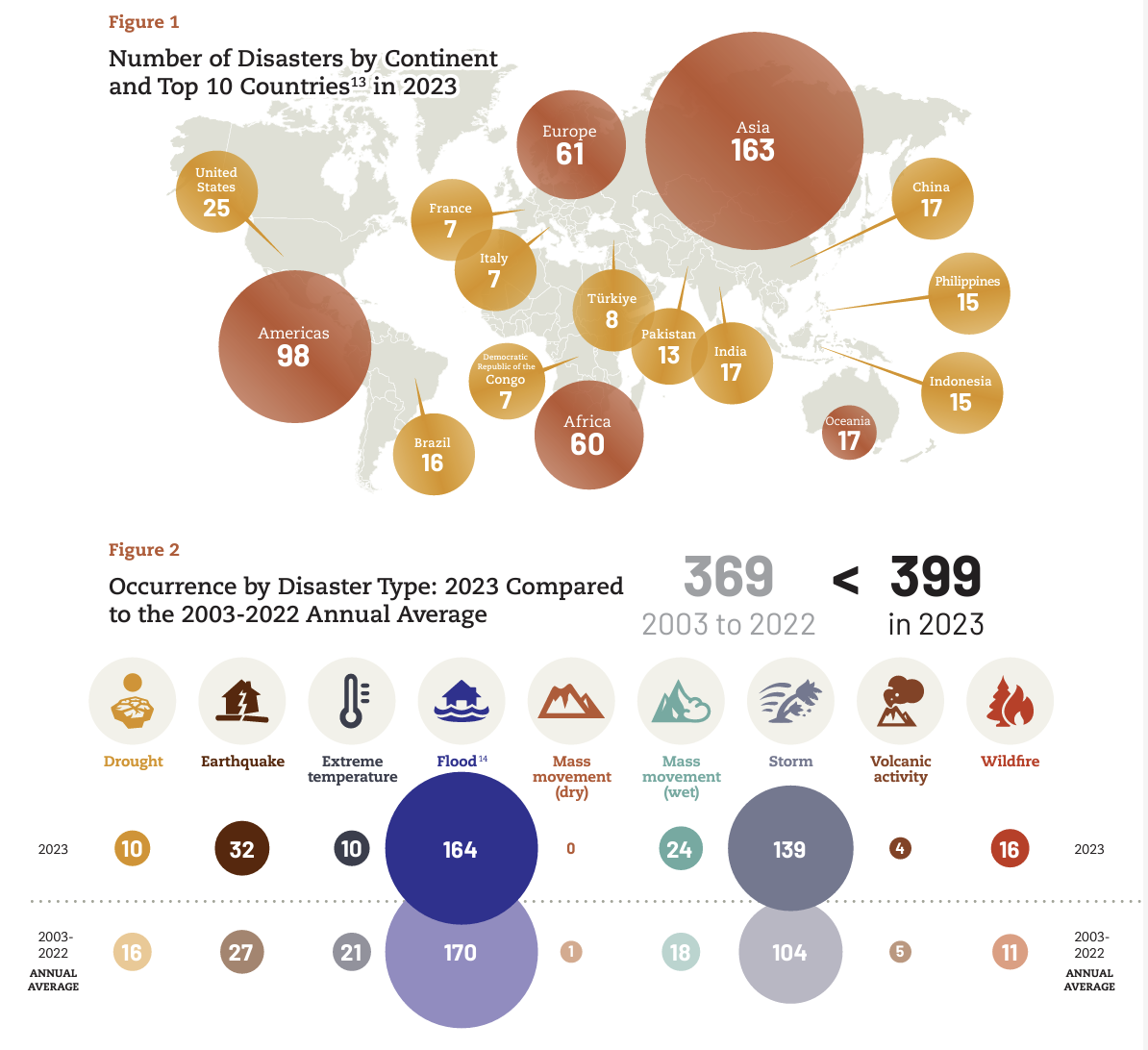

On July 8th hurricane Beryl made landfall in Texas. With winds reaching up to 265 kilometers per hour it became the Atlantic’s earliest Category 5 hurricane on record due to a combination of factors, including record warm sea temperatures in the Atlantic, which in turn are widely attributed to anthropogenic climate change. The previous month in Europe, storms led to widespread flooding in Switzerland and Italy; followed by wildfires burning through large swathes of Greece.

“Climate change is altering the frequency, intensity and sometimes even the location of extreme weather events – these changes are currently the biggest impact of climate change,” says Ilan Noy, Chair in the Economics of Disasters and Climate Change at Victoria University of Wellington and the Gran Sasso Science Institute.

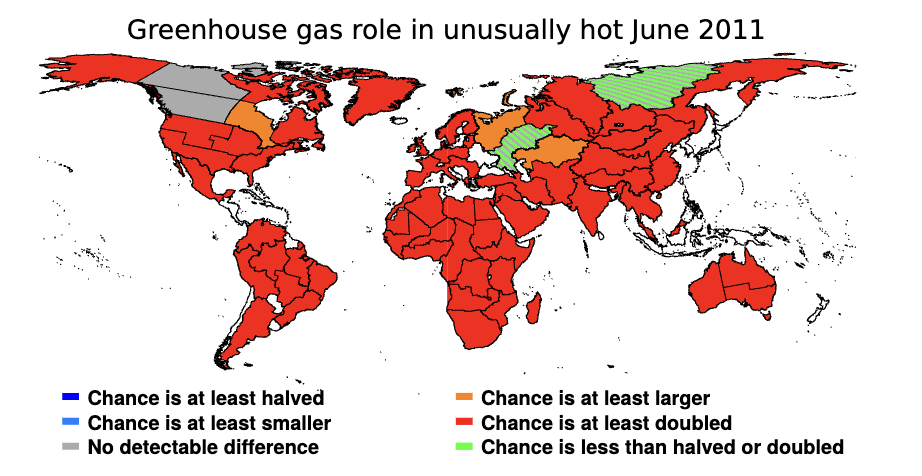

The question is, how are researchers investigating the impact and cost of climate change? Extreme event attribution science (EEA) helps identify the main contributing factors that lead to extreme weather or climate events. EEA enables researchers to establish the relative influence of global warming versus other factors such as natural variability. This has added to the growing scientific consensus on the role of anthropogenic climate change on both frequency and intensity of extreme events.

Organizations such as the American Meteorological Society provide annual reports dedicated to explaining extreme events from a climate perspective, and their 2019 report documents 168 attribution studies, of which 73% revealed a considerable link to human-caused climate change.

Although EEA is used to study how climate change influences the meteorological characteristics of weather events, there is also growing interest in understanding how these changing characteristics translate to social, economic, or environmental impacts.

To this end, more recent efforts have taken EEA one step further by looking at socio-economic impact data to develop extreme event impact attribution (EEIA) – which in practical terms means an analysis of the costs of climate change that are caused by the change in frequency and intensity of extreme weather events.

In the case of Beryl, the flooding in Switzerland and Italy, and the wildfires in Greece, future studies may use EEIA to determine not only how influential climate change was in their occurrence but also the extent of damages it caused. A valuable tool not only for economic impact assessments but one that also has the potential to inform climate change litigations, and facilitate future planning and prioritizing of climate change adaptation strategies.

What are the impacts?

What is certain is that the majority of studies involving EEIA show that climate change is exacerbating economic inequalities and hitting the poorest the hardest. This is particularly apparent when looking at studies that compare the impact of climate change across countries. A case in point is the use of EEIA as a tool in the development of the United Nations’ Loss and Damage (L&D) Fund, whereby quantifying the economic impacts of climate change on any given extreme event provides valuable information in the process of calculating how much money the L&D Fund needs, which countries the money should go to, and for what impacts.

“Over the past twenty years Small Island Developing States (SIDS) have experienced a lot more of these climate change induced or attributed extreme weather damages compared to other countries,” says Noy, who also points out that these countries are also some of the least responsible for the emissions that are leading to global warming.

Research by Noy shows that SIDS suffer higher levels of loss and damage than non-SIDS across all country-income groups, which manifests itself in impacts such as five times more climate change-attributable deaths due to extreme weather.

Furthermore, floods and storms affecting SIDS are projected to produce cumulative climate change attributable loss and damage of $56 billion under a 2°C warming scenario by 2050, adding up to an 11% increase in annual loss and damage over the next twenty three years (2023–2045) compared with the previous two decades or so (2000–2022).

“What this shows is that the poor are living in more exposed places and they are more vulnerable to extreme weather due to a lack of resources and an inability to invest in adequate resilience,” continues Noy.

A relationship that is not just limited to SIDS. In another study, Noy looks at the impact of hurricanes on public debt in the Caribbean, revealing how storms have been intensifying due to anthropogenic climate change and, in the process, causing further debt accumulation in the region. In fact, the impact of severe hurricanes on public debt that is attributable to climate change in the Caribbean is shown to increase debt by 3.8% when compared to the level of debt at the time of the event.

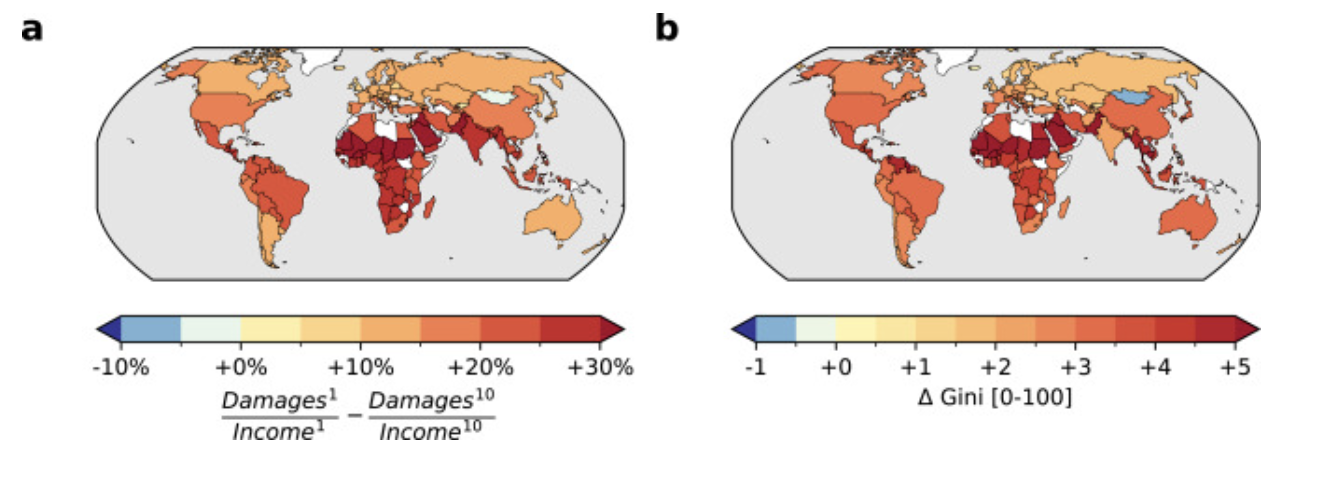

These studies add to a considerable body of literature on the impact of climate change on economic growth – and hence the effect of rising temperatures on gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates at the country-level – and how they cause increased economic inequality.

Distributional effects of climate damages by 2100 under SSP3 and BHM-Adapt damages. Panel (a): differences in damages as a share of income between D1 and D10. Panel (b): impact of climate change on the Gini index. Source: Climate change impacts on the within-country income distributions, 2024.

Looking within

In recent years there has also been a growing interest in understanding how climate change attributed extreme events impacts within-country inequalities, in both high- and low-income nations.

“Climate change is not just a global issue, but a deeply local one too,” explains Johannes Emmerling, senior scientist at CMCC and co-author of a recent study on the impacts of climate change that focuses specifically on within-country inequality.

“We found that the potential large impact of extreme weather events on GDP, amounts to almost zero on average for the richest 10% of people within countries. This is because insurance and different adaptation options are more readily available and accessible for richer households,” says Emmerling, whose study shows that for every extra 1% in income, climate damages decrease by about 0.4%.

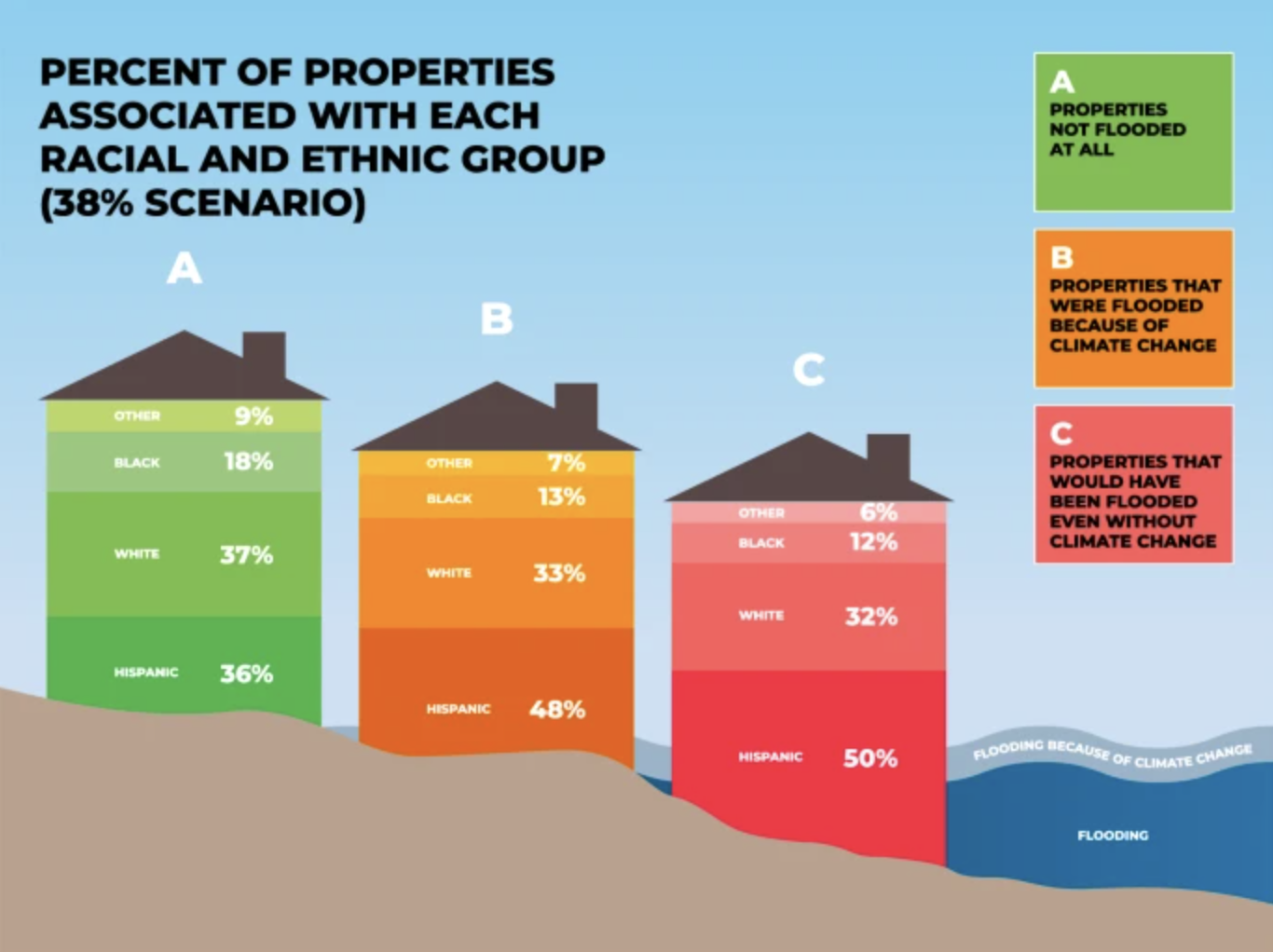

These kinds of inequalities repeat themselves across the globe and in countries with very different levels of economic development. For example, another 2022 study co-authored by Noy looks at the climate change-attributed flood depths and damages during Hurricane Harvey in Harris County, Texas. Not only does it reveal that approximately 30% to 50% of properties in Harris County would not have flooded had it not been for the increased rainfall due to climate change but also that there were significant inequalities in the climate change-attributed impacts.

“One of the things we found was that there was an ethnic imbalance in the distribution of impacts of Harvey that was causing the Hispanic population – and in particular low income and uninsured Hispanic communities – to feel the worst of the effects,” explains Noy.

“Of course it’s not the storm that is discriminatory but rather the way communities in cities are organized and, in this case, the fact that there is less investment in infrastructure like storm drains and flood barriers in low income Hispanic neighborhoods.”

A pattern that is also evident in places such as South Africa, where rising temperatures are shown to impact the poorest disproportionately. A recent study reveals a significant ∪-shaped relationship between temperature and inequality indices, whereby the more temperatures increase the greater the inequality, indicating that as temperatures increase they will outweigh potential benefits from GDP growth in the African nation.

“Climate change not only increases inequality, but increased inequality exacerbates many of the climate change-induced impacts on society through increased exposure and vulnerability,” says lead author of the study and CMCC scientist Shouro Dasgupta, whose research advocates for the importance of investigating the distributional effects of climate change at the micro-level.

Which extremes will impact us the most?

“Although we often talk about flooding as a major factor in extreme event impacts attributed to climate change, the same patterns and risks also relate to heat and heatwaves, but we know a lot less about them,” says Noy.

Understanding and quantifying the impact of heatwaves in terms of mortality and morbidity is complex as there is a need for extremely detailed data on a weekly or even daily time scale. However, in many of the countries most affected by extreme heat events this kind of data is either limited or unavailable. Hence, the majority of research conducted on the impacts of heat focuses on high income countries.

An example cited by experts is that of India. Although home to the world’s largest population and extremely exposed to heatwaves – as these occur annually – there are few comprehensive studies on their impacts. “The consequences of heatwaves are simply harder to quantify compared to the consequences of floods for example,” explains Noy.

Global databases for disasters such as EM-DAT report surprisingly low mortality rates related to heatwaves in places such as India and Sub-Saharan Africa. Researchers believe this is down to a lack of available data rather than an accurate representation of what is happening on the ground.

In contrast, heatwaves in Europe have seen a huge uptick in attention, not least of which due to the effects of the 2003 heatwave, which led to the hottest summer recorded in Europe since at least 1540, caused over 70,000 additional deaths, and has positioned heat stress resulting from heat waves as the major cause of climate-related premature deaths in Europe.

The availability of detailed data and socio-economic indicators that help assess the overall impacts and potential inequalities at a high resolution is a valuable tool for resilience planning. CMCC scientist Giacomo Nicolini leveraged this when studying the impact and potential inequalities in access to urban green infrastructure, which is one of the best-suited nature-based solutions.

In a new study published in Nature Cities, Nicolini uses socioeconomic indicators to address the environmental injustice underpinning access to green cooling solutions in fourteen major European urban areas, including Florence and Rome.

“In all the urban areas analyzed, lower-income residents, tenants, immigrants and the unemployed, experience more difficulties accessing green cooling services due to the unfavorable urban and social layout of many European cities,” says Nicolini, revealing that differing capacities for adapting to climate change are not just a matter that concerns high- and low-income countries, but is also about the social differences within the wealthy European cities.

“The data for impacts, particularly of some kinds of extreme weather events such as heatwaves, is still lacking and I think we would be shocked by their true magnitude,” concludes Noy.