On 11 December, at the COP25: High Level Event on Global Climate Action, panelists and the audience were treated to a remarkable spectacle: a Q&A session with Luca Parmitano, European Space Agency astronaut, streamed live directly from the International Space Station. A moving moment that brought the people gathered in Madrid to tackle climate change face to face with a man observing the planet from outer space. A unique opportunity to get a “different” perspective on Earth, in all its beauty and… fragility.

“From up here, we have the unique privilege of being able to look at our planet with our own eyes. An incredibly beautiful planet. However, we also see its incredible fragility. I have seen with my own eyes the terrible effects of climate change so I hope that my words can bring some strength to the somewhat hard to understand data that can feel cold to the common person.”

This week, @antonioguterres spoke via videolink with @astro_luca, on board the @Space_Station.

Watch their moving conversation about the fragility of human beings & the need for #ClimateAction to protect our one and only planet. #COP25 pic.twitter.com/M41eE3X9Yf

— United Nations (@UN) December 14, 2019

Although no one expected this COP to make a major leap forward on emissions targets, it was hoped it would help countries take a step towards increasing cooperation and pave the way for higher ambition next year, at the watershed COP26 that will be held in Glasgow, United Kingdom. Just as space exploration has at times succeeded in uniting countries and brought people together despite differences, the hope is that tackling climate change can do the same. With the aim of coordinating efforts to lower emissions, which the COPs have historically been an arena for doing.

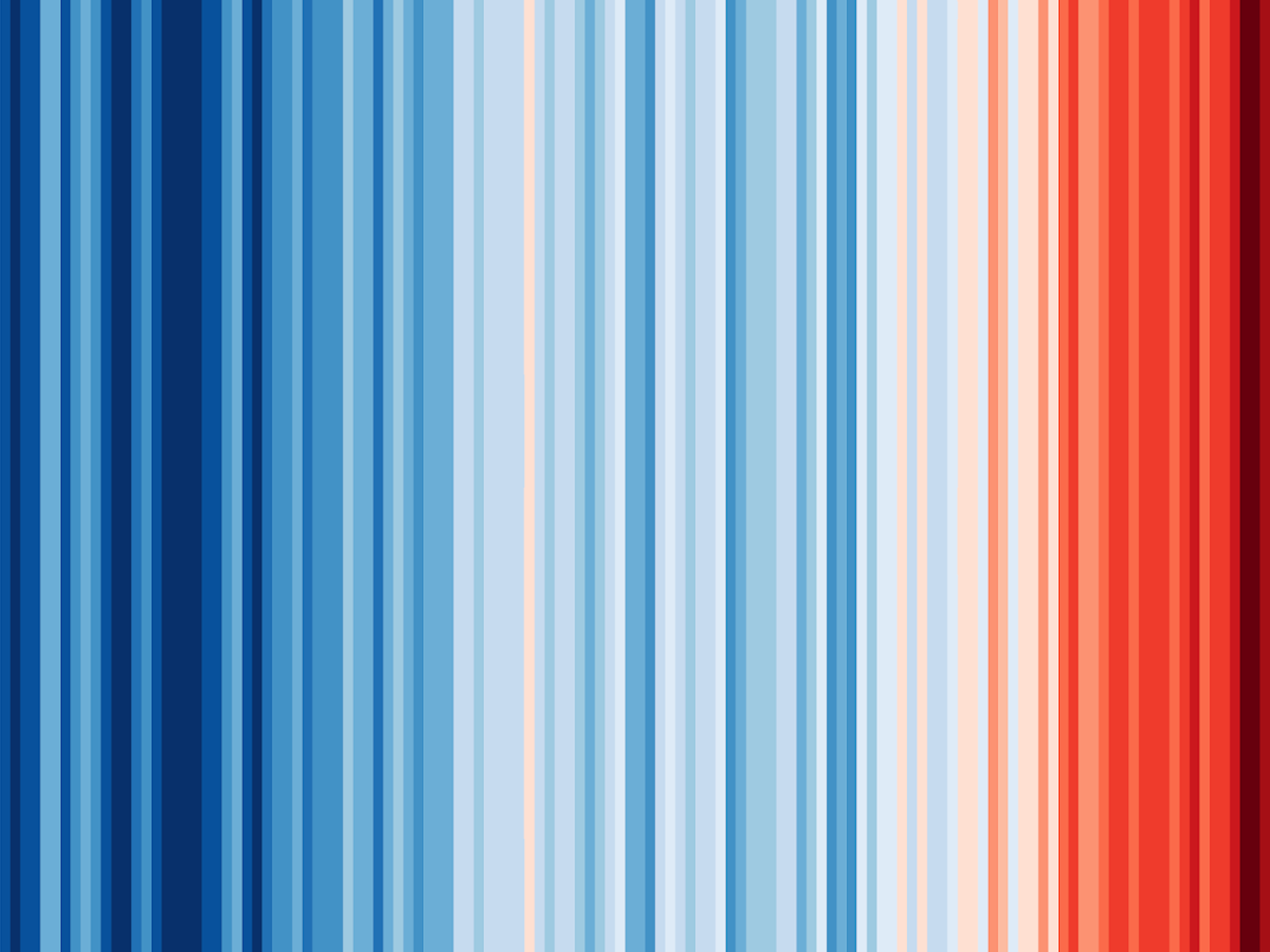

However, in the aftermath of the Madrid conference, it’s clear policymakers have struggled to create unity around significant and ambitious change. For Patricia Espinosa, UNFCCC Executive Secretary, “clearly we are not where we need to be. We are on track to double the 1.5°C goal.”

What happened at the COP25 in Madrid

Two weeks of intense negotiations in Madrid came to a close on Sunday, with many left disappointed and feeling short-handed by what should have been the “Ambition COP”. Although there was a formal and significant recognition of the gap between the targets set in 2015 and the measures needed to face the climate crisis (scientists indicate that current targets would put the world on track for 3°C of warming), some of the key issues on how to bridge this gap still remain unresolved. In particular, the lack of consensus between parties revolves around two main issues: the absence of mechanisms that would oblige increased ambition; as well as the failure to agree on Article 6 and hence the missing element in the Paris Agreement rulebook.

I am disappointed with the results of COP25. The international community lost an important opportunity to show increased ambition on mitigation, adaptation & finance to tackle the climate crisis.

António Guterres, UN Secretary General

Ambition

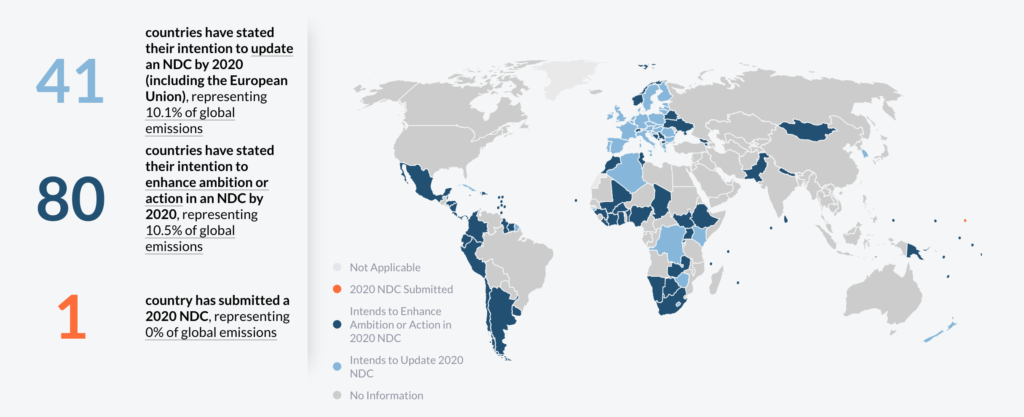

COP25 was the final summit before 2020, which in turn is the deadline year for countries to present their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Naoyuki Yamagishi, climate and energy lead for WWF Japan, told Carbon Brief that the COP25 was the “last chance, the last call to make the case for raising ambition in 2020”.

However, the final days of the conference revealed a rift in the levels of ambition of participating countries. On the one hand, just 80 stated their intention to set stronger NDCs by 2020, of which most are small and developing nations representing just 10.5% of world emissions. On the other hand, countries such as China, Brazil, India, Australia, and Saudi Arabia insisted on their refusal to increase their commitments.

Although the Chilean Presidency made ambition the flagship of the conference, the text it drafted lacked sufficient references to specific timeframes and placed no legal requirements to step up NDCs by 2020. According to Mohamed Adow, director of Power Shift Africa, “in Madrid, governments have turned their backs on raising ambition, at a time when we need more than ever to heed the scientific warning – act now or pay a terrible price later.”

That said, the final text does emphasize the emissions gap between what countries are pledging and what is needed to remain within the Paris objective of keeping global temperatures well below the 2°C mark. It also indicates that new climate pledges to be presented in 2020 must “represent a progression” on previous ones and should also be of the “highest ambition”.

The agreed text of 1/CMA.2 “re-emphasizes with serious concern the urgent need to address the significant gap” between current ambition and the goals of limiting warming to well-below 2°C. Furthermore, paragraph 7 “urges parties to consider [that] gap” when they “[re]communicate” or “update” their NDCs, whilst shying away from proposing a fixed timeline.

Although it is a far cry from the Ambition COP that many had hoped for, not all is lost and some significant progress has been made in setting the groundwork for COP26 in 2020.

Article 6

A lot of the pressure on COP25 revolved around solving the last part of the Paris Agreement “rulebook”: Article 6 (which deals with carbon markets and other forms of international cooperation). However, parties fell short of reaching a deal and will have to go back to the negotiating table in 2020, both at the intersessional meeting in June and at COP26 in November.

Particularly strong opposition to Article 6 came from Brazil (reminiscent of its position at the COP24 in Katowice), seeking to insert loopholes and caveats that would have lead to weak rules and hence risk undermining already-insufficient ambition by allowing targets to be met on paper even as levels of CO2 in the atmosphere continue to rise.

Countries are finding clever ways around having to take real action, like double counting emissions reductions and moving their emissions overseas and walking back on their promises to increase ambition or refusing to pay for solutions or loss and damage.

Greta Thunberg, Climate Activist.

The final text on Article 6 released on Sunday only contains two sets of brackets, in contrast to the numerous ones found in the first week of negotiations (unresolved issues are left in brackets): a step in the right direction for creating consensus and a demonstration that most points of contention have been ironed out and therefore laying the groundwork for future negotiations in 2020. The two main sticking points continue to be accounting rules to regulate instances of double counting, and the possibility of transferring Kyoto carbon credits.

In fact, lack of an agreement on Article 6 is not necessarily a bad thing and may actually be the lesser of two evils. Eleonora Cogo, Senior Scientific Manager in the Climate Simulation and Prediction division at CMCC, who participated at COP25 negotiations, claims that “overall it was a better outcome to have no decision on carbon markets rather than having a decision that would allow double counting or the use of credits generated under the Kyoto Protocol. Better to have no decision on this rather than a bad decision.”

Furthermore, although parties were unable to reach consensus on Article 6 some countries joined to establish the “San Jose Principles”; described by the Costa Rican environment minister Carlos Manuel Rodriguez as “a definition of success on Article 6”, as they stress the need for a consensus that would “prohibit the use of pre-2020 units, Kyoto units and allowances”, and “ensure double counting is avoided”. The San Jose Principles were signed by around 30 countries (including many EU member states) and represent a set of principles for High Ambition and Integrity in International Carbon Markets, that constitute the basis upon which a fair and robust carbon market should be built.

Looking on the bright side

Although there is much to be disappointed with, there are other positive notes emerging from the COP25.

The first concerns civil society’s strong role in applying pressure on policymakers, demanding that they listen to the science behind climate change. In Madrid, 500,000 people took to the streets to demand action and once again Greta Thunberg stole the show. Eleonora Cogo comments that “Greta was the catalyst for civil society and the center of attention who even put seasoned politicians in the shade.”

In terms of policy and commitments, on 12-13 December, EU heads of state managed to agree on the goal of making the continent “climate neutral” by 2050. The European Commission went on to reveal a “European Green Deal”, that has the potential to allocate at least 25% of the long-term budget to climate action. President Ursula von der Leyen described it as Europe’s “man on the Moon” moment and a measure that sets the example for other countries.

Finally, although Madrid was not able to tackle some key issues, it is important to note that nothing that happened at this COP precludes progress in 2020. In the words of Eleonora Cogo: “Even at this COP there has been some progress. It has not all been a waste of time as countries have increased their understanding of each others’ position. But it has definitely raised the stakes for the next COP where countries will have to present their updated NDCs.”