It has been a hard winter for mountain enthusiasts across the globe, as changing snowfall patterns and environmental factors such as anomalous heatwaves in the European Alps and firestorms in the US have left ski resorts on thin ice.

Yet, snowfall is not just important for ski resorts and the winter sports industry but also a vital ingredient in the balance of glaciers; regulating climate (snow is reflective and therefore bounces incoming sunlight back into space); and ensuring water supply through the melting of seasonal snow, which provides drinking water and water for crops for countless people across the globe.

Although studies on the cryosphere are a well-known and documented phenomenon, how climate change is affecting snowfall patterns is less talked about with recent studies looking at both overall snow cover (the amount of land covered by snow at any given time) and snow mass (depth of snow) and how these have been changing over the last few decades.

“We can project the future changes in snowfall and snow cover using climate modelling system, which is one of the computer simulations based on the physics, in the late 21st century. The snowfall and snow cover are strongly influenced by the temperature changes,” explains Hiroaki Kawase, senior researcher at the Japan Meteorological Agency.

Global change in snowfall patterns

“Global climate models project that snow cover will decrease due to global warming in most parts of the world. However, there is large variability across the regions, whereby other factors such as latitude and elevation will play an important role,” says Kawase.

Kawase goes on to highlight further complexities in the relationship between warming and snowfall: “Although the overall decrease in snowfall is larger under a higher emissions scenario, our research also shows that in the short-term extreme snowfall, such as daily snowfall, will be enhanced. This is because of the increase in water vapour due to atmospheric and ocean warming due to global warming.”

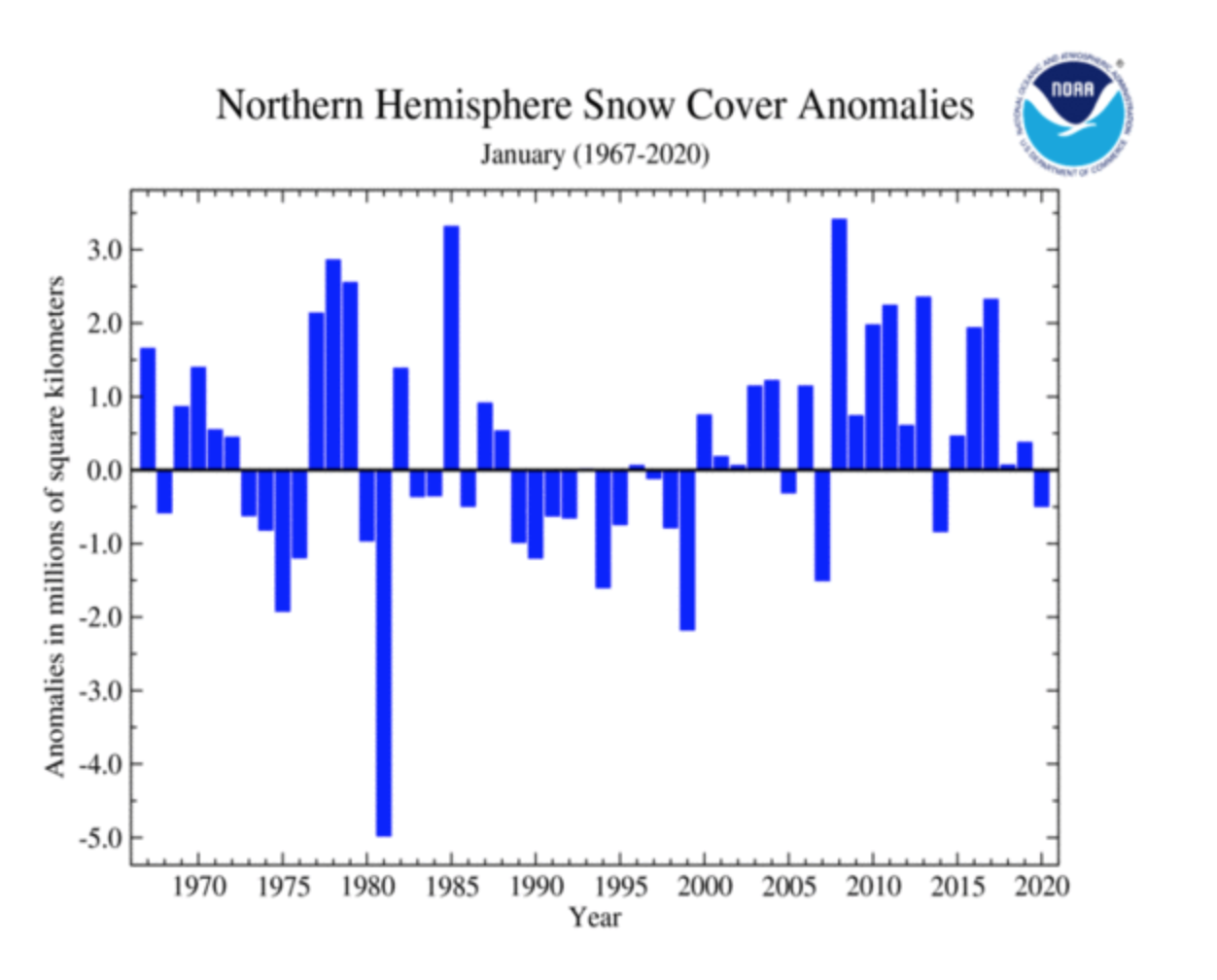

In January 2020, over the entire northern hemisphere, snow cover extent was 490,000 square km below the 1981–2010 average. This amounts to the 18th smallest January snow cover extent in the 54-year period of record.

A significant factor in this drop were the warmer-than-average conditions which spread across much of the region, particularly in Russia, where temperatures were a staggering 5.0 degrees Celsius above average.

In contrast, Alaska and western parts of Canada experienced cooler than average temperatures, although this was not sufficient to make up for the overall snow cover in the northern hemisphere, which was at its smallest since 2014.

Studies indicate that the below-average snow cover extent observed across much of Europe and parts of western Russia is part of a trend that will continue in the next two decades. “We see a clear decrease in the long-term trend of snow,” says Dr. Kari Luojus, head of Satellite Services and Research group at Finnish Meteorological Institute, in an interview with Euronews.

❄️snow researchers from @FMI_Snow and @environmentca have reliably estimated the trend in northern hemisphere snow since 1980.

Snow cover extent has ⤵️

Snow mass has remained the same in Eurasia, but ⤵️ in North America. @nature paper athttps://t.co/9QBgNm1Jij pic.twitter.com/fkJZLyrdU5— World Meteorological Organization (@WMO) May 22, 2020

Data from Dr. Luojus’ study indicates that, although the amount of snow (or snow mass) in Eurasia has remained relatively constant and dropped in North America, both regions are experiencing a marked decrease in snow cover extent, indicating that snow may continue to melt away earlier and earlier in the season.

Ski areas struggle with changing snowfall patterns

Reduced snow cover is impacting winter sports enthusiasts and skiers across Europe are having a particularly hard time. After the 2020-21 season was a write-off due to covid restrictions, that kept many ski resorts closed, the 2021-22 season is being impacted by a lower-than-average snowfall that is threatening the livelihoods of people living in areas that rely on winter sports tourism.

More worryingly, this is not a phenomenon that only relates to Europe. Across the globe, ski areas are experiencing extremes and significant changes in snowfall patterns which are increasingly being linked to climate change.

Japan, which is famed for high amounts of snowfall in the winter seasons and is home to the snowiest inhabited place on Earth, Sukayu Onsen in the Northern part of the country (that receives an average yearly snowfall of 17.6 metres), is also experiencing changing snowfall patterns that have already had an impact on ski resorts.

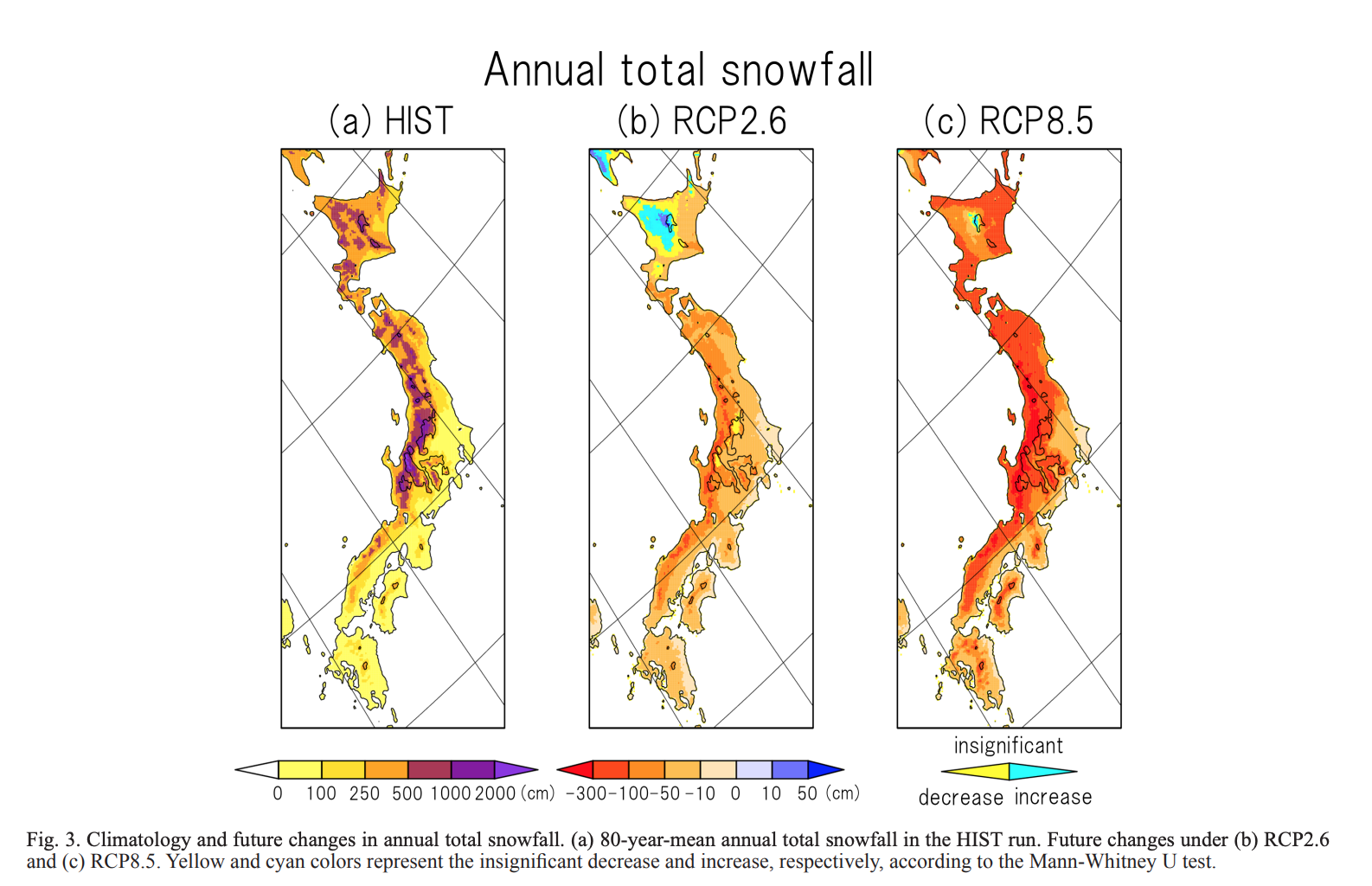

Studies led by the Japan Meteorological Association show that: “Since the late 1980s, snow cover has been decreasing over the Japanese archipelago, especially in the central and western parts of Japan.” According to Kawase the main effect will be at low elevations: “Under a high emissions scenarios, we will have sufficient precipitation (snowfall and rainfall) but snowfall will largely decrease at the low elevations.”

A situation that will also present itself under a low emissions scenario: “Under RCP2.6 [a low emissions scenario], the annual total snowfall decreases in most parts of Japan except for Japan’s northern island, Hokkaido. In Hokkaido, the winter snowfall increases even under RCP8.5, especially in January and February. The snowfall peak is delayed from early December to late January in Hokkaido,” continues Dr Kawase.

Not only changes in the timing and amount of snowfall but also other environmental elements such as firestorms can negatively affect ski resorts and therefore winter sports enthusiasts and the communities that rely on them for their livelihoods.

The US, where climate change has compounded the risks associated with forest fires, is particularly vulnerable. Approximately 60% of US ski resorts rest on forested areas and are therefore vulnerable to this threat, which could adversely affect an industry that is worth 788 billion USD.

“Until we get legislation on a federal level that tackles the problem, it’s really about adaptation and mitigation,” says Mike Reitzell, the president of Ski California, an industry group that represents 35 resorts in California and Nevada when talking to the New York Times. “Fortunately, adapting is something we’re really good at.”

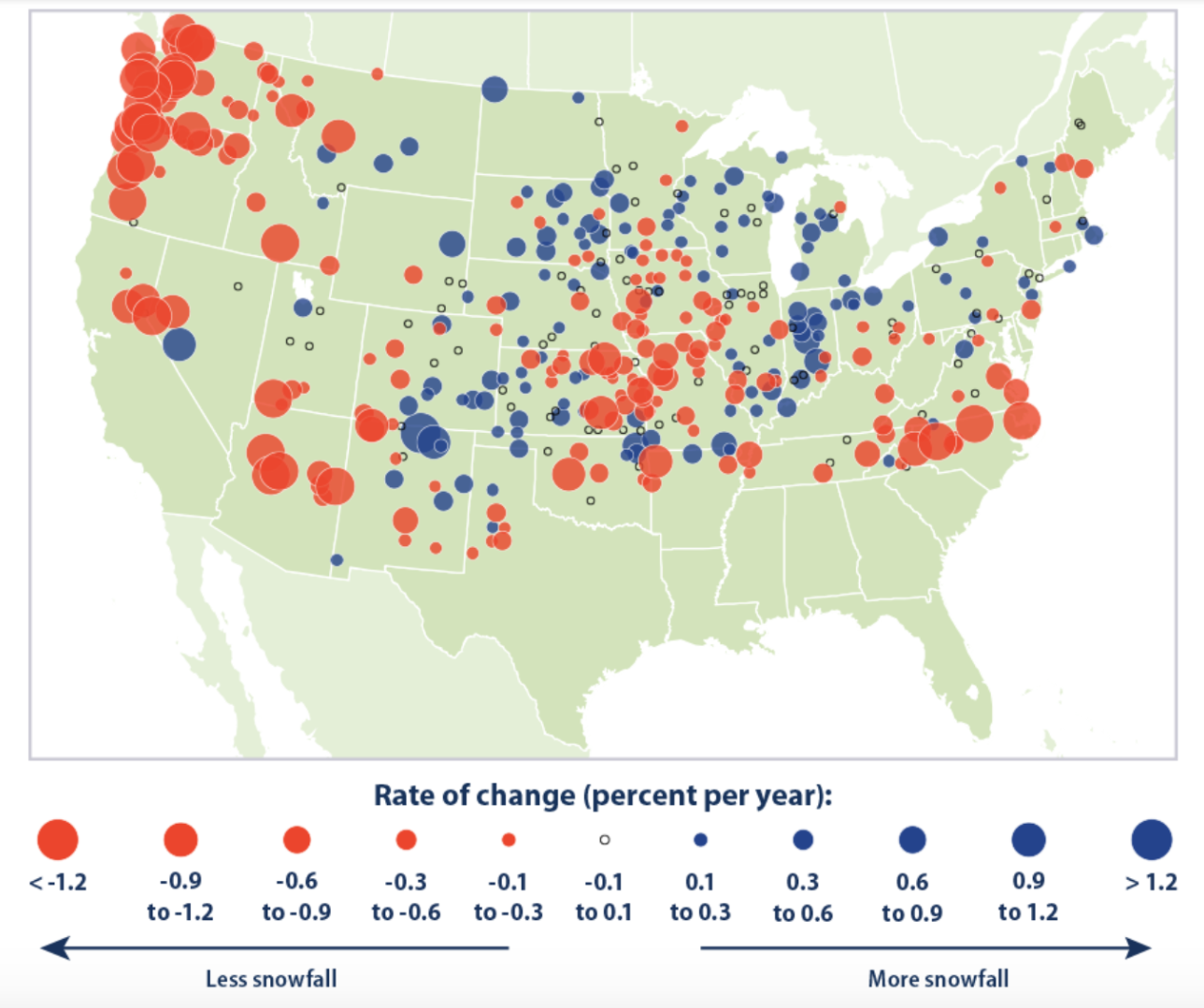

In US mountain ranges, such as the Rockies and Cascades, snowmelt is a primary source of water and it has shrunk by an average of 19% between 1955 and 2020, according to Environmental Protection Agency data.

Ski seasons across the US and Europe are being cut short. The US ski season, in the decade after 2010, shortened for the first time in 40 years. In Europe, the areas surrounding Mont Blanc are witnessing an earlier encroaching of spring by 2 to 5 days every decade.

The financial burden

The economic impacts have been dire. In 2018 a report by the University of New Hampshire and Colorado State University revealed how five of the lowest snow cover winters in the 2001-2016 period cost the ski industry an estimated 1 billion USD and 17,000 jobs per season.

In the French Alps the small resort of Schnepfenried in France experienced exceptionally warm weather and changing snowfall patterns which have put the resort at risk of closure. “The weather conditions were very particular with a lot of rain and wind,” admits Nicolas Buhl, Manager of the Schnepfenried resort when speaking to Euronews.

In Japan, low elevation resorts will be the most affected. According to Yojiro Fukushima, director of the Tourism Commission of Hakuba Village – one of the largest ski resorts in Japan – “Ski resorts hire a lot of workers. “We are more worried about global warming than COVID-19. The mountains are not the same as they used to be.”

“The Sanosaka Snow Resort, which is a low elevation resort and part of Hakuba Valley, stopped operations this winter after more than 40 years,” Fukushima says. “The resort’s business was struggling before COVID-19, due to the lack of snow and high temperatures at low elevations.”