Fossil fuels have formed the cornerstone of the global energy system, bringing unprecedented economic growth and fuelling modernity. Global energy use has increased fifty-fold in the last two centuries, powering the industrialization of human society, but also causing unprecedented environmental damages. CO2 levels in our atmosphere have reached the same levels as those registered 3-5 million years ago, when average temperatures were 2-3°C warmer and sea level was 10-20 meters higher. The scientific community has reached a consensus on the anthropogenic nature of climate change, with the IPCC stating that “Human influence on the climate system is clear, and recent anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases are the highest in history.”

In response to the climate crisis, global agreements have centered around reducing CO2 emissions so as to curb temperature increases and curtail anthropogenic climate change. A central pillar of these efforts revolves around revolutionizing the energy sector and moving towards a low-carbon economy. This will require an imminent shift towards renewable energy, given that the energy sector accounts for two-thirds of global emissions. In the past, a major sticking point in this transition has been the economics behind a move away from fossil fuels: how will we pay for this transition and compensate for countless lost jobs? Now, the picture is changing. There is mounting evidence that the numbers behind a clean energy revolution make sense.

Responding to rising CO2 levels

According to the World Meteorological Organization’s (WMO) 2018 study, atmospheric greenhouse gas levels, namely carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O), all reached new highs in 2017. “The science is clear. Without rapid cuts in CO2 and other greenhouse gases, climate change will have increasingly destructive and irreversible impacts on life on Earth. The window of opportunity for action is almost closed,” claims WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas.

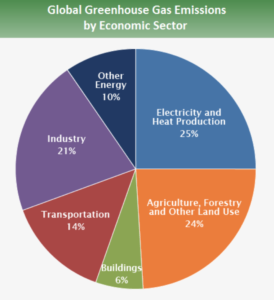

The energy sector accounts for around 35% of CO2 emissions. This includes the burning of coal, natural gas, and oil for electricity and heat (25%), as well as other emissions not directly associated with electricity or heat production, such as fuel extraction, refining, processing, and transportation (a further 10%).

The energy sector accounts for around 35% of CO2 emissions. This includes the burning of coal, natural gas, and oil for electricity and heat (25%), as well as other emissions not directly associated with electricity or heat production, such as fuel extraction, refining, processing, and transportation (a further 10%).

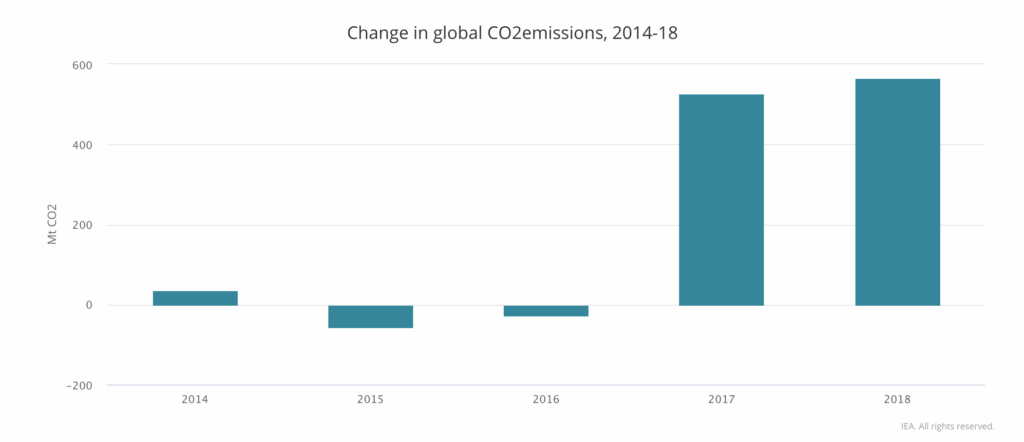

Not only does the energy sector contribute to the lion’s share of emissions, there is also a continuous growth in demand for energy. Driven by a strong global economy, as well as higher heating and cooling needs, global energy consumption increased by 2.3% in 2018, almost doubling the average rate of growth since 2010.

Man’s thirst for energy is also fuelled by climate change itself: a catch-22 situation, whereby emissions create more extreme temperatures which in turn lead to more emissions. A study by Enrica De Cian, scientist at CMCC Foundation and Team Leader at EnergyA, “indicates that climate change could increase global energy demand up to 17% in 2050 under vigorous warming. Climate-induced changes in energy demand would be much larger in tropical regions with a 32% increase”. For example, since 2000 the use of energy for air conditioning services in the residential sector has been increasing steadily, with growth rates above 15% per year in countries such as China, Turkey and Malaysia. Cold snaps increase demand for heating and, to an even larger extent, warmer summers drive demand for cooling. Just one of the many vicious cycles which the current energy paradigm engenders.

The result? Global energy-related CO2 emissions rose 1.7% to a historic high of 33.1 Gt CO2 in 2017. While emissions from all fossil fuels increased, the energy sector accounted for nearly two-thirds of the growth in emissions. In the United States alone gas consumption jumped 10% from 2016, the largest increase since the beginning of IEA records in 1971.

In this context of rising demand and increasing emissions the IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming claims that it is still possible to remain within the 1.5 °C mark set out in the Paris Agreement. However, this will require net-zero emissions by 2050 and therefore decarbonizing the economy. Decarbonization equates to removing or reducing carbon dioxide from energy sources and therefore implementing a wholesale clean energy revolution, shifting away from fossil fuels and embracing renewable energy. A vital ingredient if we are to contrast the worst effects of climate change.

Not “just” about doing the right thing

The benefits of a clean energy revolution are not limited to “just” averting the climate crisis. “There are ancillary benefits that would go beyond reducing global warming. For instance, reduced air pollution will have a positive impact on human health” comments Ramiro Parrado of CMCC’s Economic analysis of Climate Impact and Policy Division when interviewed for this article. On top of health gains, countries are also choosing to source their energy from renewable sources so as to become less dependent on energy imports, particularly countries that do not produce oil. In this way, geopolitical tensions are averted as countries generate their own power.

However, although the advantages of an energy transition for better health, geopolitical stability and environmental gains are no news; they have never been enough to bring about a clean energy transition. As is often the case, what really makes the world go round is money… and now money is finally moving in the right direction.

A growing body of literature points to the fact that the clean energy revolution would come hand in hand with GDP growth and increased employment. The influential 2019 IRENA report indicates that for every USD 1 spent on the energy transition there could be a potential payoff of between USD 3 and USD 7, or USD 65 trillion and USD 160 trillion in cumulative terms over the period to 2050. Enough to get major industrial players and policymakers seriously interested.

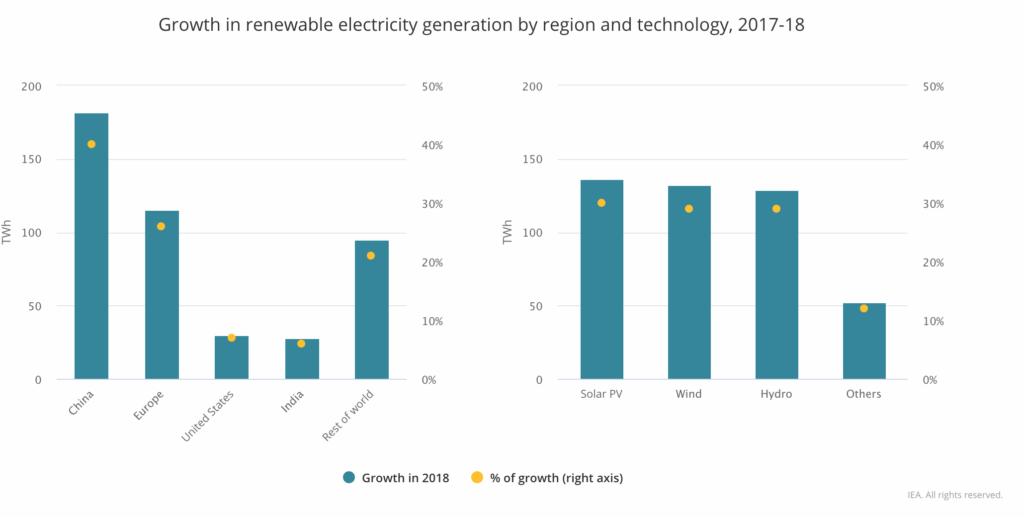

Once regarded as unreliable and too expensive, renewables are becoming the hallmark of decarbonization plans. A major factor has been the fall in costs, which is driving the business case for renewable energy. Renewable technologies such as hydropower and geothermal have been competitive for years and now solar and wind are gaining a competitive edge as a result of technological advances and increased investment, competing with conventional generation technologies in terms of cost in many of the world’s top markets, even without subsidies.

Ramiro Parrado explains that: “From the point of view of power generation, the costs of renewable energy have been decreasing fast. This has led to an increase in their share of final energy consumption and, at the same time, attracts more investments in the renewable sector. This trend will continue in the future and trigger a transition where the economy will rely much more on renewable energy sources instead of fossil fuels.”

Since 2010, the average cost of electricity from solar and wind energy has fallen by 73% and 22% respectively. Estimates indicate that by 2020 the average cost of solar and wind-generated electricity will be lower than that of fossil fuel electricity. And the problem of electricity storage, which has hindered the establishment of renewable energy in the past, is also being tackled effectively. Lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles have had an 80% decrease in costs of production since 2010. IRENA predicts that by 2025 the global weighted average cost of electricity could fall by 26% for onshore wind, 35% for offshore wind, at least 37% for concentrated solar power (CSP) technologies, and 59% for solar photovoltaics; with the cost of stationary battery storage potentially falling by up to 60%. These factors are leading to competitive business models that bring “for-profit” players into the mix and thus boosting the clean energy transition.

Another strong indicator of the financial benefits of a clean energy transition is the decision by major financial players to divest in fossil fuel energy and invest in renewables. The Norwegian sovereign wealth fund and HSBC are implementing measures to divest from coal, with the former recently dumping investments in eight oil companies and over 150 oil producers. When speaking about the Norwegian fund’s move, Tom Sanzillo, director of finance for the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, said: “These are very important statements from a big fund. They’re doing it because fossil fuel stocks are not producing the value that they have historically. It’s also a warning to the integrated oil companies that investors are looking at them to move the economy forward to renewable energy.”

Investment groups, such as DivestInvest and CA100+, are also putting pressure on businesses to reduce their carbon footprints. At COP24 alone, a group of 415 investors, representing over USD 32 trillion, voiced their commitment to the Paris Agreement: a significant contribution. Calls to action include demanding that governments put a price on carbon, abolish fossil fuel subsidies, and phase out thermal coal power.

But, what about all those jobs that would be lost if we move away from the fossil fuel industry? Parrado explains that: “As in every transition there will be sectors that will be affected and moving away from fossil fuels will imply job losses in that sector.” However, forecasts predict that the number of new jobs created will actually outweigh job losses. Employment opportunities are a key consideration in planning for low-carbon economic growth and many governments are now prioritizing renewable energy development, firstly to reduce emissions and meet international climate goals, but also in pursuit of broader socio-economic benefits such as increased employment and wellbeing.

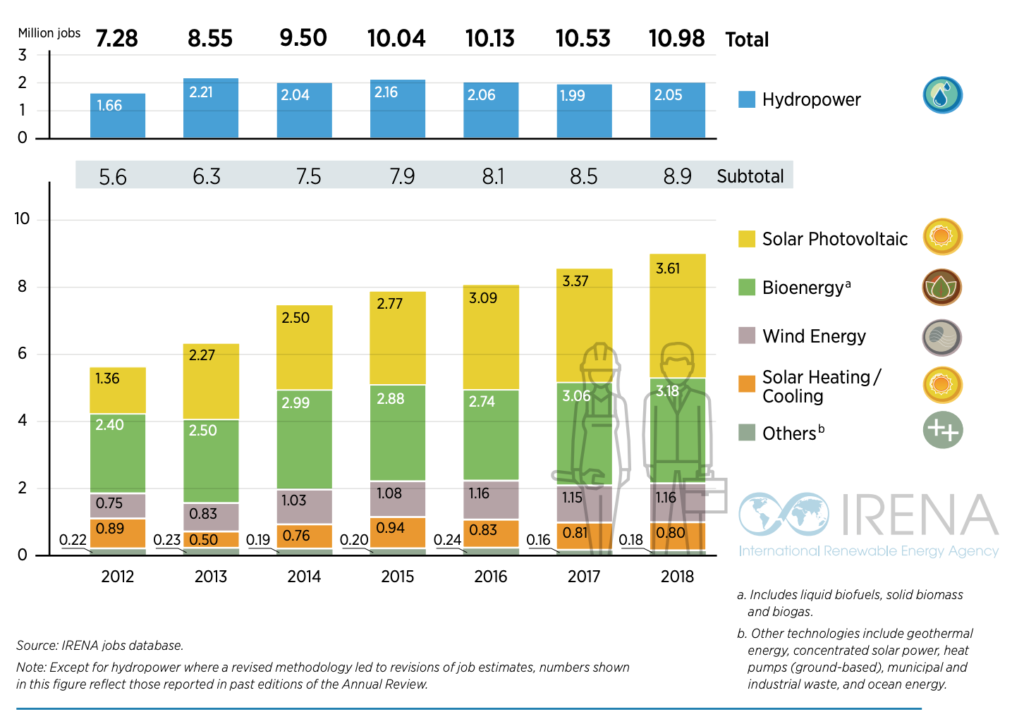

Following a trend of steady growth worldwide, the renewable energy sector employed a record 11 million people by the end of 2018, according to the sixth edition of the Renewable Energy and Jobs series. Forecast models indicate that total employment could increase by 0.2% globally in 2050 if a clean energy transition is implemented.

A clean energy transformation will come hand in hand with economic benefits across the board, including global GDP growth. Although we should move away from our obsession with GDP, as the economist Dan Button points out, the clean energy transition is also giving positive signals in this arena. Even if the effects on economic growth and GDP are difficult to predict it is believed that a transition to renewable energy could bring a 2.5% increase in GDP by 2050. This is echoed by further studies that indicate a correlation between renewable energy consumption and economic growth, a view that the UNFCCC endorses: “Achieving a 36% share of renewable energy in the global energy mix by 2030 would increase global GDP by up to 1.1%, roughly USD 1.3 trillion.”

On this note, Ramiro Parrado adds that: “In addition, it is important to include the avoided costs of climate change which according to reports could add an additional positive impact on GDP of 2.8% in 2050.” Although there continues to be uncertainty as to the exact figures, what is certain is that all actions that have a successful impact on climate change mitigation efforts will also be beneficial to the economy.

A clean energy future

The current energy paradigm makes us associate energy use with the destruction of our planet. This is because we have burnt fossil fuels in exchange for access to cheap and abundant energy services. However, if we are to tackle the climate crisis energy will continue to be a key component both in the implementation of the adaptation and mitigation strategies needed to cope with the current climate crisis and in the continued prosperity of our society. Energy is both the reason for our problems and the instrument with which to solve them.

The economics behind the transition are sound and, coupled with other dynamic forces for change, there is newfound hope in a clean energy future.