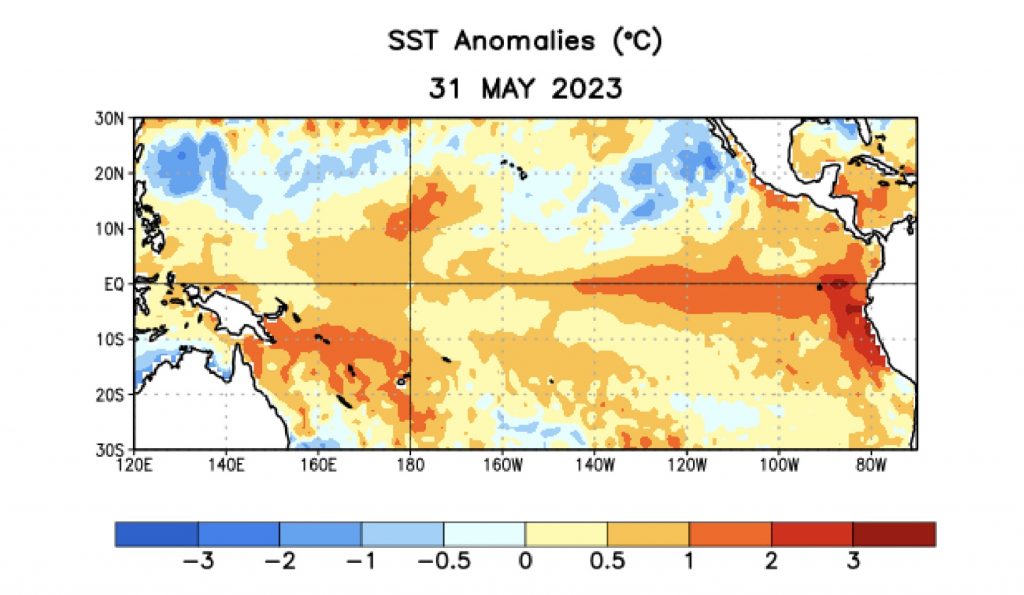

In recent months, surging temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific led meteorologists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) center to declare that an El Niño year was imminent. On the morning of July 8, this went from prediction to reality as NOAA announced that: “El Niño conditions are present and are expected to gradually strengthen into the Northern Hemisphere winter 2023-24.”

This has set off alarm bells as record warm years, such as that of 2016, which ranks as the hottest on record, and an intensification of extreme events often coincide with powerful El Niño cycles.

What is the El Niño Southern Oscillation

El Niño is just one of three phases of a climate pattern known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation – or ENSO for short – with the other two known as La Niña, and the neutral phase.

The term El Niño first came into use as far back as the 16th century when colonists in Peru noticed a curious climatic phenomenon that brought a juxtaposition of abundance in crop yields on land – due to greater than usual rainfall – and destruction at sea – as uncharacteristically warm and nutrient scarce waters caused fish stocks to plummet.

Although coming at seemingly irregular intervals and lasting for varying periods of time, the phenomenon always made itself obvious in the coastal towns of Peru around December, leading local fishermen to associate it with Christmas and hence give it the name El Niño.

What the Peruvians couldn’t have imagined at the time, and scientists took centuries to uncover fully, was that the anomaly affecting the eastern Pacific shores was just the first domino in a knock-on effect whose impacts would ripple around the globe.

In fact, just as an El Niño brought an abundance of rain and impoverished fish stocks to the east Pacific tropical coasts, it was not uncommon for phenomena such as drought in Australia and parts of Asia, flooding on the West coast of North America and disruption to the normal hurricane formations over the Atlantic to occur during the same year.

“The name ENSO (El Niño-Southern Oscillation) itself actually alludes to both the oceanic and atmospheric parts of the equation that influences global and local climate,” says Leone Cavicchia CMCC researcher and expert in climate simulations and predictions. The El Niño part of the name addresses changes in ocean temperatures, and a localized phenomenon in the Pacific Ocean, whereas the Southern Oscillation part refers to the atmospheric aspect connected to trade winds that travel across the globe.

“Knowledge of the deep interconnection between the ocean system and atmosphere system and how they influence each other continuously and at different scales is a relatively new phenomenon,” continues Cavicchia, who highlights how, even just half a century ago, it would have been more common to study the ocean and the atmosphere separately.

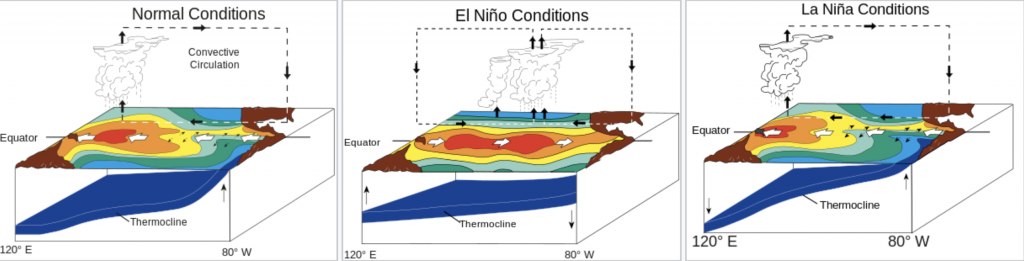

Yet ENSO drives home that the two need to be looked at in unison for a complete understanding of weather patterns. During normal conditions, trade winds blow from east to west along the equator, which in turn moves warm water from South America towards Asia. Just as this warm water shifts west, cold water wells up in the East to replace it.

In a La Niña year – typically referred to as the cooling phase of ENSO – this process is intensified with stronger east-to-west trade winds. In an El Niño year, the opposite happens, whereby trade winds are disrupted, and warm water tends to accumulate in the South American Pacific.

Although the intervals at which these three phases alternate are irregular and hard to predict, El Niño and La Niña episodes usually occur every two to seven years and typically last between nine to 12 months, although the recent three years of La Niña are a – not unprecedented – exception.

As El Niño and La Niña have such a large influence on the temperature of the tropical Pacific—the world’s largest ocean—this, in turn, significantly influences not just what happens in the region but all around the globe.

Furthermore, as we only just exited a triple La Niña phase in February, which typically brings global temperatures down, the worry is what the effects of a sudden switch to El Niño will be, both in terms of the intensity of the phase itself and its impacts on both local and global climates.

What to expect from El Niño

With El Niño now officially upon us, the question has already started to revolve around what the effects will be. First of all, El Niño phases can vary in intensity, from strong to weak, and this can cause large differences in their impacts.

For example, some of the strongest El Niño events ever registered, in the winters of 1982-1983 and 1997-1998, led to significantly higher than average rainfall in North West America. Yet, precipitation levels on the West Coast were much lower with weaker El Niño cycles.

A strong El Niño in 1997-98 is believed to have cost over 5 trillion USD and around 23,000 deaths from storms and floods. Currently, scientists at NOAA are predicting that the chances of an intense cycle for the 2023-24 winter stand at around 55%, and about 84% that it will be at least moderate.

Zeke Hausfather, climate research lead at Stripe, tweeted that El Niño’s development means there is about a 30% to 50% chance that 2023 will set a record for the warmest year in instrument records, which date back to 1850, therefore surpassing 2016.

With five months of the year now in (and using the latest El Nino forecasts), there is a roughly 33% chance that 2023 will end up beating 2016 as the warmest year on record in the ERA5 dataset: pic.twitter.com/UIK5o76JY5

— Zeke Hausfather (@hausfath) June 5, 2023

“Although predicting when and how strong ENSO phases will be has become quite accurate, there is still a lot of uncertainty about how these impacts will be felt on a very localized scale,” says Cavicchia.

“Basically, we can predict with a relatively high degree of certainty that there will be more rainy conditions in some parts of North America, for example, but we can’t say exactly where the flooding will be and to what degree it will occur.”

ENSO and climate change

Another cause for concern is how a strong El Niño phase will interact with a world that is already anomalously warm due to climate change, with some talk of the heat leading to breaches in climate thresholds such as the 1.5C above pre-industrial levels set out in the Paris Agreement.

“WMO is sounding the alarm that we will breach the 1.5 [degree Celsius] level on a temporary basis with increasing frequency,” said WMO secretary-general Prof. Peter Taalas in a news release.

El Niño has arrived officially! @NOAA has issued an Advisory with a 56% of a strong episode by winter. Let the “not so” fun begin. https://t.co/AbT3wkVcas pic.twitter.com/epuplrapCE

— Jeff Berardelli (@WeatherProf) June 8, 2023

Yet talk of thresholds being breached and the consequences that this may have in the long term may be premature.

“What can happen is that depending on the ENSO phase in which we are, there may be an amplification or dampening of the effects of climate change,” says Cavicchia. “We have to remember that climate change isn’t a strictly linear process, and ENSO can highlight the ups and downs in what is a general warming trend. For example, the last three La Niña years may have given a reduced perception of how much the planet is warming.”

For Cavicchia, it is important to “not confuse natural variability with human influence on climate. Thresholds need to be calculated in the long term so that they aren’t influenced but short-term fluctuations such as an El Niño phase.”

In fact, the effects of climate change on the intensity and frequency of strong ENSO phases is also a matter of debate on which the scientific community has still not reached a consensus.

In the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Working Group 1 report on the Physical Science Basis of Climate Change ENSO is also discussed, revealing how, over the last 10,000 years or so, ENSO’s history has always come with a wide range of different patterns and amplitudes.

The WGI Report concludes that there is no clear evidence that there have been any significant changes since 1950 in ENSO and also goes on to state that climate model simulations that do not include rising greenhouse gases produce similarly large variations in ENSO behavior over long periods of time due solely to the chaotic nature of the climate system.

“There is still too little consensus between different climate models on the relationship between climate change and ENSO,” confirms Cavicchia, who does, however, discuss how recent studies indicate an increase in frequency and intensity of strong phases under a warming climate.

“However, that doesn’t take away from the fact that in terms of impacts of extreme weather, these short-term fluctuations such as the incumbent El Niño may be extremely powerful.”