On the cold windswept coast of Patagonia, scientists have been working to uncover the mystery of a sunken ship which was discovered on the shores of the Golfo Nuevo, Argentina.

Archaeologists have been analyzing the ship’s carcass, comprised of mostly well-preserved timber, for years and although they have long believed it to be the Dolphin, a whaler which went missing in 1859, it was only until recent analysis of tree rings, by dendrochronologists from Argentina’s Laboratory of Dendrochronology and Environmental History, that they took a vital step towards establishing its identity with virtual certainty.

“I cannot say with a hundred per cent certainty, but analysis of the tree rings indicates it is very likely that this is the ship,” explains one of the lead researchers Ignacio Mundo when talking to the Columbia Climate School.

But, what exactly was it in the ship’s recovered timber that allowed for it to be identified as the missing whaler? A key aspect involved working with Ed Cook, founder of the Lamont-Doherty (LDEO) Tree Ring Lab, who is a pioneer of dendroarchaeology – the science of establishing where old wooden structures come from and when they were built.

Cook has been instrumental in the development of the North American Drought Atlas, a collection of tree ring samples from approximately 30,000 living trees of different kinds found across the North American continent.

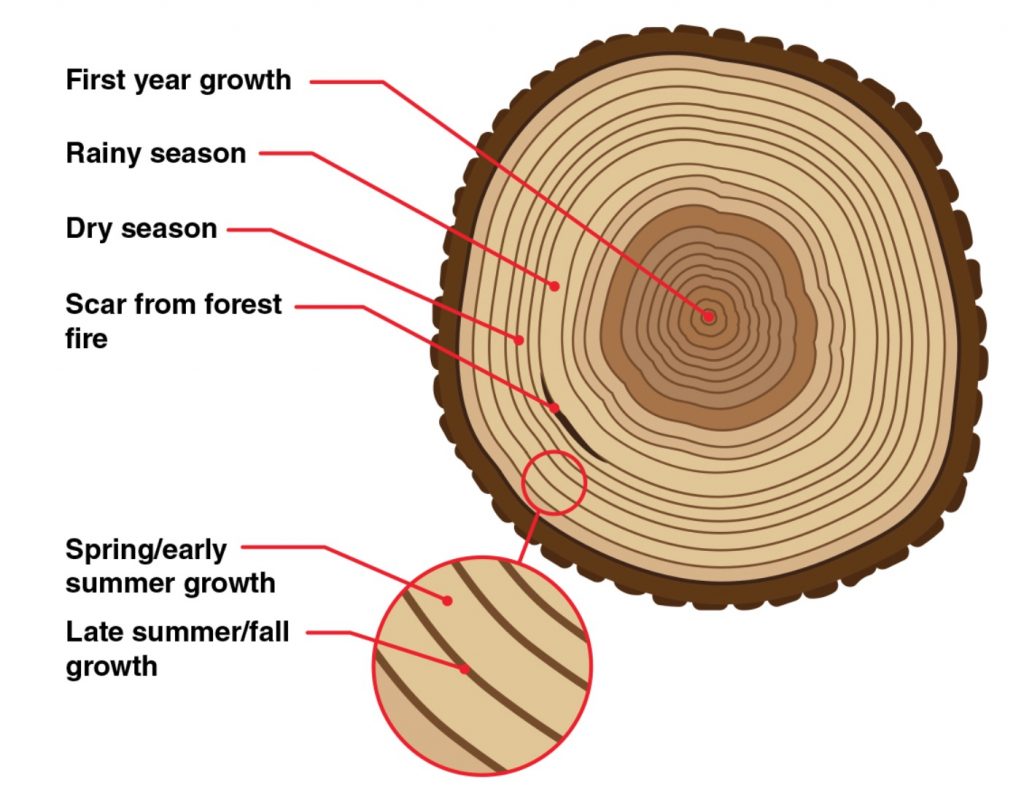

When looked at closely, tree rings reveal the age of trees and at the same time the varying levels of yearly rainfall or temperatures they experienced over the course of their lives. A valuable window onto understanding past climates but also the origins of timber used in constructions or ships.

Scientists can therefore look for clues in tree rings, found in both live trees and old timber, that help solve mysteries such as that of the Dolphin. In this case, Cook’s Atlas of North American trees allowed researchers to establish that the timber found on the shores of the Golfo Nuevo belonged to trees which sprouted in 1679, with outer rings indicating that they were cut in 1849: a perfect match with the Dolphin’s year of construction, 1850, and therefore adding one more vital piece to the puzzle of the ship’s origin.

How does dendrochronology work?

Tree rings function as remarkably reliable natural archives, revealing the stories of the trees themselves and the areas that surround and shape them. This is because trees are sensitive to their local climate and as they grow and add to their girth each year they respond to factors such as temperature and precipitation. When subjected to warm, wet years their rings tend to be wide, whereas the opposite conditions lead to thin ones.

Tree ring research, known as dendrochronology, literally “the study of tree time”, involves looking at parameters such as total ring width, early and late wood ring width, density, cell wall and cell lumen area, stable isotopes of different elements, chemical composition as well as specific features of the wood.

Dendrochronology is a widespread practice in North America and Western Europe leading to extensive open access databases such as the International Tree-Ring Data Bank.

“Silent though they are, the trees, it turns out, can speak volumes. The size, density, anatomy and chemistry of each ring reflect the environmental conditions in the year in which it grew. So like ancient scribes, long-lived trees can sensitively record the environmental history of a given place and time,” writes Gordon Jacoby, Co-Founder of LDEO Tree Ring Lab on the research center’s website.

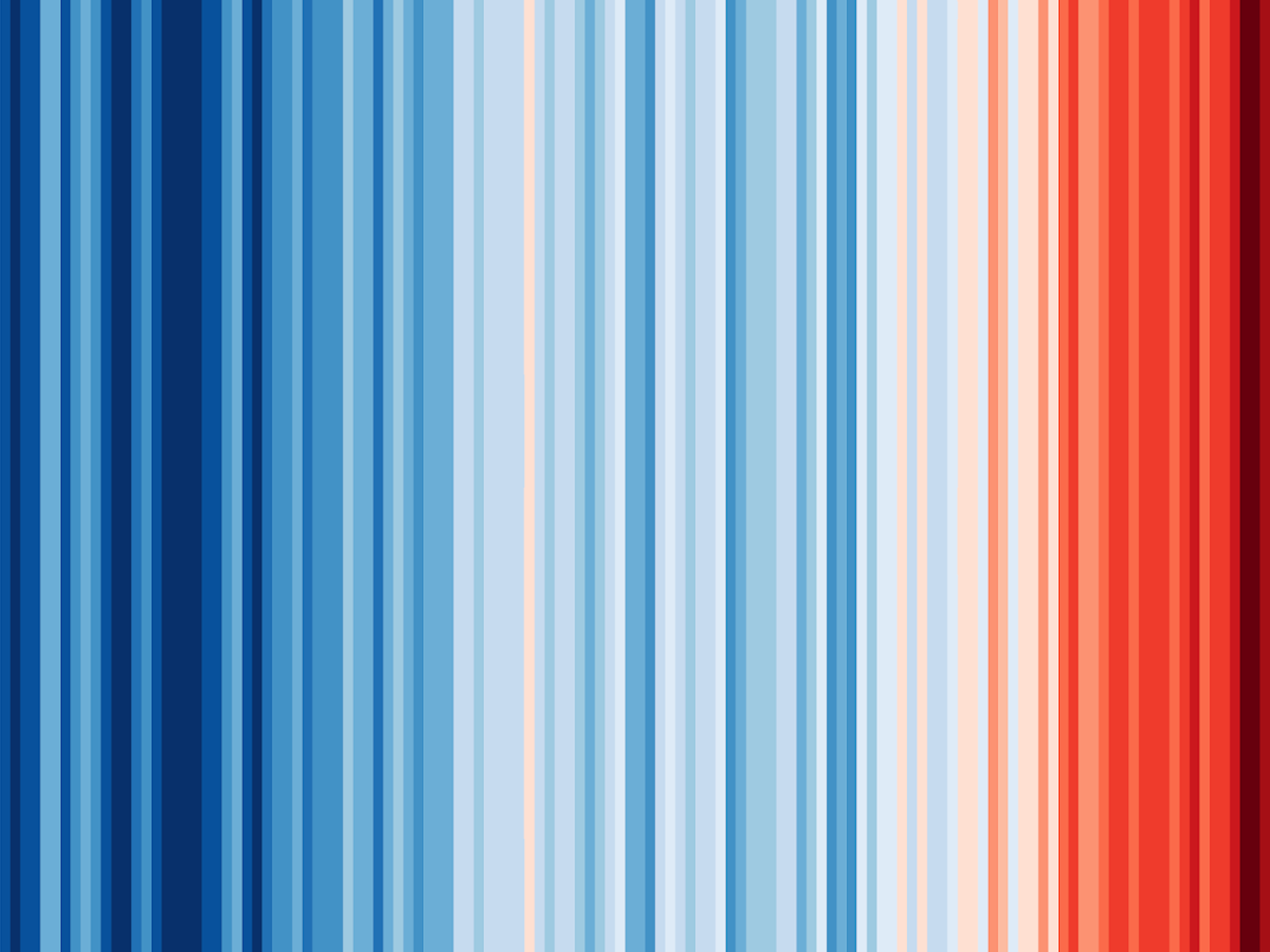

More recently, rising concern about climate change has brought a turn towards using dendrochronology to look at past climates in what Stephen E. Nash, a historian of science and an archaeologist at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, terms dendroclimatology.

“This fascinating science uses tree rings to reconstruct ancient precipitation, temperature, and other climatic variables. Unlike various instruments for tracking weather, tree rings provide researchers with a record going back hundreds or even thousands of years,” explains Nash when writing on Sapiens.org.

Trees mirror the climate

Tree ring datasets offer a vast resource with which to learn about past climate conditions and hence learn more about the changes we are experiencing today.

Researchers from the Institute of Plant and Animal Ecology, Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Science (RAS), and the Ural Federal University have been gathering data in the Yamal Peninsula, north-western Siberia, for the past 40 years, collecting subfossil wood for analysis.

The Arctic is as warm as never before: A unique collection of tree ring samples that were gathered in more than 20 expeditions shows that.https://t.co/K1DB5rVQR8#treeringresearch #globalwarming #dendrochronology@NatureComms @FontiPat pic.twitter.com/Kz7n2Iko2W

— WSL Umweltforschung (@WSL_research) August 25, 2022

Stepan Shiyatov, a pioneer of dendrochronology in Russia, was the first to start collecting data in the region and his work, published in the journal Nature Communications, reveals that northwestern Siberia is now experiencing its warmest summers in the past 7,000 years. Furthermore, his research shows that the region was cooling for several millennia before it made a u-turn in the 19th century when temperatures began to increase rapidly.

“Due to changes in the Earth’s orbit we would have expected a continuous, slow and gradual decrease of incoming summer solar energy, and thus temperature, at the subpolar latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere during the last 8–9 millennia,” says Rashit Hantemirov, leading dendrochronology researcher, when talking to Earth.com.

“However, [as] recorded by the trees growing in Yamal, this cooling trend was interrupted in the middle of the 19th century, when the temperature began to rise very quickly and reached the highest values in recent decades. The exceptionality of the modern warming is corroborated by observations that the last century was characterized by a total lack of cold extremes contrasted by the occurrence of 27 extreme warm years, 19 of which have fallen in the last 40 years,” continues Hantemirov.

Using tree rings to look this far back into the region’s climate past is essential as instrumental observations are more recent and incomplete, particularly in Arctic regions.

Researchers posit that these climatic patterns provide more evidence that the current anthropogenic warming cycle interrupted a multi-millennial cooling trend. Furthermore, industrial-era warming is shown to be not only unprecedented in rate but also to have elevated summer temperatures to levels above those reconstructed for the past seven millennia (in both 30-year mean and the frequency of extreme summers).

Similar studies using dendrochronology are also taking place to research the climate of north-west Europe, including the UK, over the last 4,500 years, with a new Swansea University-led project recently receiving €3 million in European funding.

This is significant as past tree ring research has not been as effective in regions that experience mild climates which rarely limit tree growth, making dating more difficult and bringing down the reliability of the information extracted.

However, the new project relies on a change in tactics and will focus not only on the width of tree rings but also on the chemistry of the wood in question. Researchers will be analyzing the stable (non-radioactive) isotopes of the fundamental elements: carbon, oxygen and hydrogen.

“Unlike ring width, these isotope signals are just as reliable in trees from areas where growth is not strongly limited by climate. Our aim is to better understand the climate of the past, and for this we need an improved chronology of when things happened. Our ability to date wooden artifacts and timbers from antiquity will be enhanced significantly through this project. Together we hope that these advances will transform our knowledge of past climate and the dating of wooden artifacts and structures,” explains Professor Neil Loader of Swansea University, who leads the QUERCUS project, when talking to EurekAlert.

This will give a boost to understanding climate change in the region. For example, tree rings have already been extremely important in the study of variability of flow of the Colorado River and the investigation of megadroughts in the western USA, even revealing that the ongoing drought affecting the region would be only about 60 percent as severe in the absence of anthropogenic climate change.