The 2000s saw a record number of natural disasters, the majority related to the climate and, in particular, a rising intensity in extreme weather events connected to climate change. Major institutions and scientists concur that the brunt of the effects of global warming have been, and will continue to be, borne by lower income countries, meaning that those who can least afford it will pay the highest price.

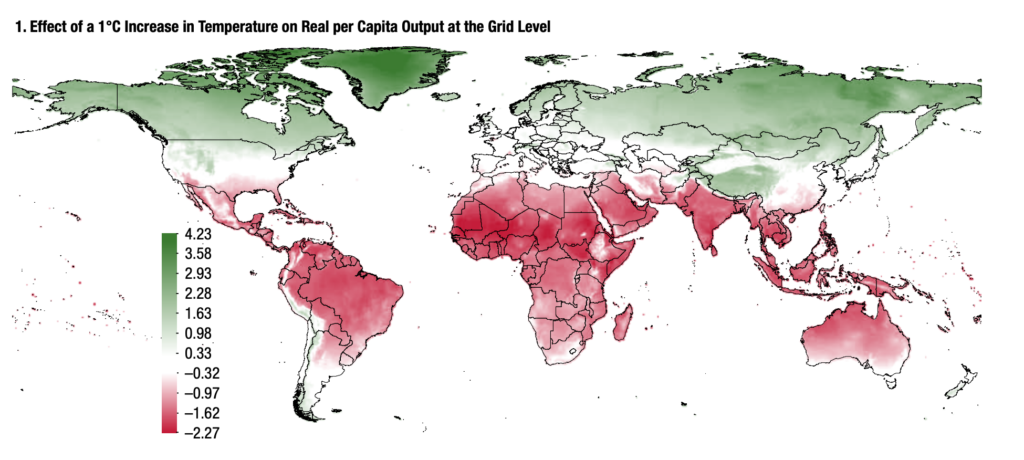

Evidence suggests that this is because less developed nations tend to be situated in some of the hottest parts of the Earth, which in turn will be most affected by rising temperatures, climate variability and an increase in the damaging effects of climate change.

What is worse is that these same countries are also less equipped, due to limited resources and weak governance, to implement the adaptation, mitigation and redevelopment strategies they so desperately need. Although climate change finance has focused on mitigation, it is becoming increasingly evident that there is also a need to help disadvantaged states cope and adapt. However, loans for low income countries affected by climate change are, on average, more expensive than for developed countries, meaning that when disaster strikes, it is often followed by sharp spikes in national borrowing: the climate debt trap.

Low income countries suffer the most

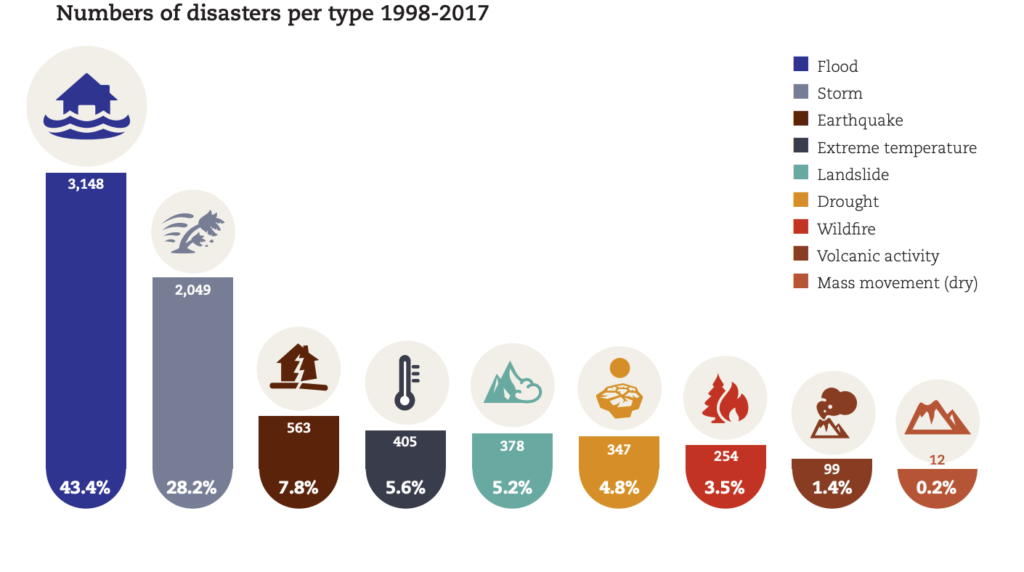

The number of reported direct economic losses due to natural disasters rose from US$ 895 billion between 1978 and 1997, to almost US$ 2,300 billion over the past 20 years. Furthermore, a UN report shows that climate-related phenomena were responsible for 91% of all recorded disasters over the past 20 years, with floods and storms being the most common offenders. When these findings are added to those of studies such as the IMF’s World Economic Outlook, which indicates that most of the negative effects of these disasters are felt in tropical countries (and almost all low income countries are found in tropical areas), then the picture looks especially dire for the world’s most vulnerable communities.

Climate vulnerability indexes further confirm this trend, indicating that three quarters of low income countries and a third of small island states are extremely or highly vulnerable to climate change compared to a quarter of the rest of the world. In fact, although high income countries such as the USA and Japan, as well as emerging economies such as China and India, all experienced the highest total cost of damages, it is low income countries that suffered the most in terms of annual average percentage losses relative to GDP. Hence, countries facing the largest increases in temperature variability also have the least economic potential to cope with the impacts.

There is now evidence of falling public spending in countries hit by high debt payments, further undermining progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals.

Tim Jones, Head of Policy at the Jubilee Debt Campaign.

This means that in impoverished areas, climate change is causing and will continue to cause the most problems. These include lower agricultural output, reduction in the productivity of workers due to heat exposure, slowing investments, and damages to health. A UN Study indicates that close to 60% of the world’s population lives in countries where an increase in temperatures will contribute or is contributing to these adverse effects, which will in turn have a substantial impact on their economies.

The result? The countries most exposed will have to implement the strongest adaptation policies and build resilience. However, it is also true that countries with policy buffers – such as lower public debt and flexible exchange rates (which are common characteristics of high income countries) – tend to experience somewhat smaller output losses from temperature. Yet again placing low income countries at a disadvantage.

Higher borrowing costs bring more debt

Charles Donovan, director of the Centre for Climate Finance and Investment at Imperial College Business School, calls the situation a “cruel irony”, by which the countries most in need of loans and investment to adapt to climate change are also having to deal with higher debt costs.

Our analysis confirms that countries with higher vulnerability to climate change risk bear an incremental cost on government-issued debt.

Charles Donovan.

A seminal report on the cost of capital in developing countries highlights that, of the most damaging disasters since 2000, 80% of them have been tropical storms and that the worst of these disasters brought government debt to rise in 90% of cases within two years (if debt relief was not granted in the aftermath). As many of these low-income states are already indebted, climate disasters, and the further indebtedness that they bring with them, are creating serious challenges for development.

A seminal report on the cost of capital in developing countries highlights that, of the most damaging disasters since 2000, 80% of them have been tropical storms and that the worst of these disasters brought government debt to rise in 90% of cases within two years (if debt relief was not granted in the aftermath). As many of these low-income states are already indebted, climate disasters, and the further indebtedness that they bring with them, are creating serious challenges for development.

Therefore, as climate-related natural disasters increase, low income countries are paying higher interest on loans for adaptation and redevelopment projects, giving rise to the climate debt trap. Examples of this abound: in 2000 and 2001, Belize was struck by two devastating storms. In 1999, Belize’s government debt was 47% of GDP but by 2003 it had doubled to 96%. Grenada was also heavily indebted when hurricane Ivan struck in 2004. In the aftermath, debt rose from 80% of GDP to 93%. More recently, Mozambique was hit by Cyclone Idai, which killed over 1,000 people, and then Cyclone Kenneth. A quick succession of extreme weather events that are putting the country under huge strain with the IMF granting loans for rebuilding, adding over USD 118 million to its already huge debt.

Sarah-Jayne Clifton from the Jubilee Debt Campaign claims that rising debt due to climate change is an issue of “climate justice”, whereby helping low-income countries cope with its consequences is a moral duty. “It is a shocking indictment of the international community that impoverished countries have to borrow from international institutions in order to cope with the devastation caused by Cyclone Idai. Emergency grants should be available to all impoverished countries in response to disasters like Idai, especially those linked to the climate breakdown primarily caused by richer countries in the global North.”

In fact, the impact of tropical storms will continue to have an incremental effect on low income countries, “as climate change will bring a reduction in total tropical storms whilst at the same time increasing their intensity”, explains Enrico Scoccimarro, Senior Scientist at CMCC whose main research activity is to investigate the relationship between tropical cyclones and the climate. “Tropical storms create lasting damage through wind, precipitation and storm surge [..] damages which are felt for months and even years after the events, depending on a country’s ability to cope with the aftereffects. Furthermore, the increase in intense cyclones associated with sea level rise that we are experiencing will increase the damage that they create.” A sea level rise that low income countries have contributed little towards creating: considering average per capita emissions in the period from 1990–2015, countries with the lowest emissions tended, however, to have the largest increases in climate variability.

If the notion that low income countries are less responsible for the current climate crisis is factored in, then the matter becomes a question of climate justice. Professor Debarati Guha-Sapir, head of the Centre for Research on Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED), comments: “Those who are suffering the most from climate change are those who are contributing least to greenhouse gas emissions. The economic losses suffered by low and lower-middle income countries have drastic consequences for their future development.”

More than “just a moral question”

The climate debt trap highlights the need for international efforts to contribute to global efforts for resilience building and hence stop climate-related natural disasters leading to a debt trap. This is important for the entire globe, as it will not only help with the development of low income countries but also contribute to meeting the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. The climate debt question is not just a moral issue of compensating climate change losers, that are also ironically (and cruelly) those least responsible for our current crisis, but also a collective issue regarding global development and climate change mitigation.

As world leaders meet in Bonn for the UN Climate Change Conference (SB50), the important issue of climate finance is taking centre stage. Executive Secretary Patricia Espinosa stated that developed countries must be reminded of the obligation to mobilize USD 100 billion annually in funding for developing countries by 2020 for action on mitigation and adaptation. A fundamental measure if we are to respect the Paris Agreements and tackle the cruel irony of climate debt.