A recent study by the ifo Institute has called into question the green credentials of electric vehicles, indicating that over their entire lifecycle certain models may cause more CO2 emissions than a comparable diesel engine. Other studies have been quick to rebuke this, claiming that the extra emissions associated with electric vehicle production are compensated by reduced emissions from driving. Regardless of who is right, the debate highlights that if a move towards electrification is to contribute to global climate goals then energy production must transition towards low carbon solutions.

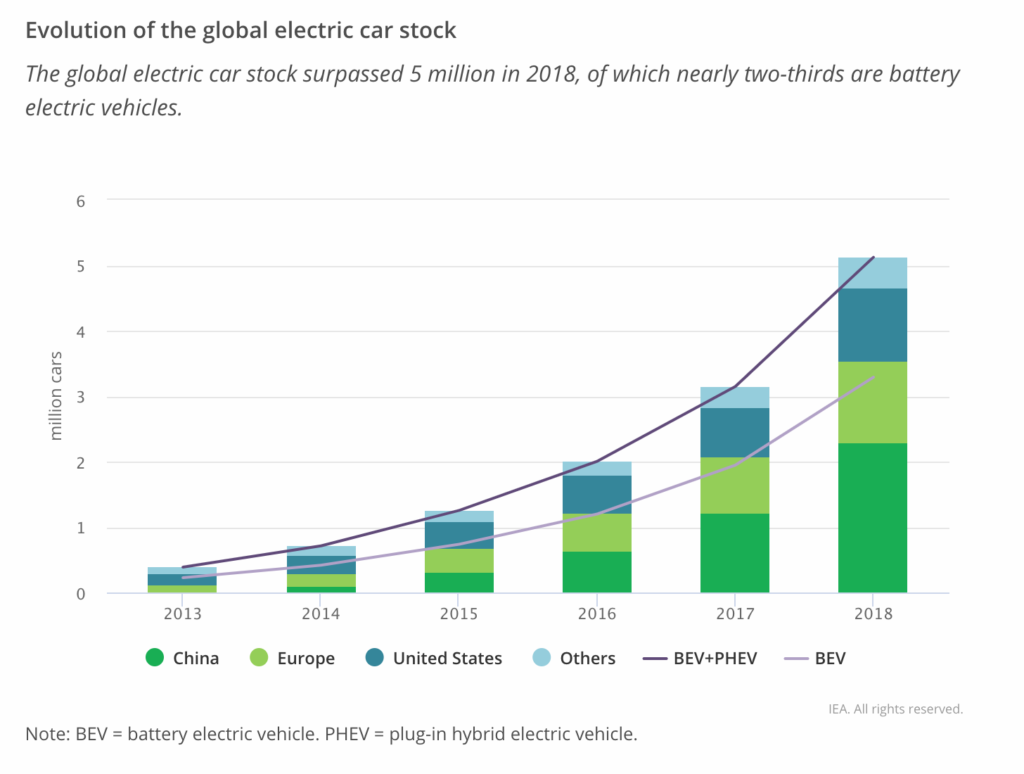

Electric cars feature heavily in plans for meeting our global climate goals and the automotive industry is investing strongly in the electrification of vehicles. A recent Reuters report, that analyses the budgets of 29 of the world’s top automakers, indicates that there will be a 300 billion USD investment globally on electric vehicle technology in the next five to ten years. Over 3 million electric vehicles were sold in 2017, and 2018 became a record-breaking year for global electric car sales (1.98 million), raising total global stock to 5.12 million according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). In fact, companies such as VW plan to build up to 15 million electric vehicles (EV) by 2025, including 50 pure electric and 30 hybrid-electric models.

As the electric vehicle (EV) market grows, there has also been a mounting debate on their green credentials, with a focus on how effective they really are in lowering harmful emissions. Although according to vehicle registration statistics, EVs do not release a single gram of CO2, this is misleading as emissions are released both when generating the electricity used to power EVs, as well as during the vehicle manufacturing process. Quantifying these emissions has led to a heated debate and conflicting studies on EVs.

A new study by the Munich based think tank ifo institute has thrown further petrol on the flames (or, excuse the pun, water on the circuit boards). The study takes two comparable car models (a diesel Mercedes and an electric Tesla) and calculates that building both cars requires more or less the same amount of CO2 — 8.6 tonnes per car. It also calculates that producing a diesel motor causes slightly higher emissions (0.8 tonnes) than making the electric motors (0.3 tonnes) and those additional components for the Mercedes create just 1 tonne of CO2 compared to the 1.5 of the Tesla, largely due to a large amount of energy needed for the mining, production and recycling of lithium, cobalt, and manganese, used in electric car batteries.

A counter-study by the Union of Concerned Scientists released detailed calculations on the benefits of electric vs internal combustion engine cars. They claim that the extra emissions associated with EV production are already offset by reduced emissions from driving (indicating that it takes just 8,000 kilometres to “pay-back” the extra emissions) and will continue to decrease as technology improves. This is confirmed by other more recent studies that also rebuke the ifo findings: one claims that EVs have emissions up to 43% lower than diesel vehicles and the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research in Heidelberg (IFEU) conducted a detailed lifecycle assessment of the carbon footprint of EVs, concluding that: “in all cases examined, electric cars have lower lifetime climate impacts than those with internal combustion engines. Furthermore, their ecological advantage over conventional vehicles will continue to grow in the future as industry taps opportunities for reducing carbon emissions in power generation and vehicle production.”

Although the ifo study has been largely debunked because of the parameters and data used in their calculations, it has further confirmed the notion that the success of EVs as means with which to reduce emissions is wholly reliant on our ability to decarbonise our energy sources. In fact, the significant differences in the calculations of the conflicting studies can often be attributed to what energy mix is used to calculate the emissions related to manufacturing and running of EVs. As electricity generation becomes less carbon-intensive, then EVs will become ever more efficient compared to conventional vehicles.

The green credentials of EVs, therefore, depend on rapid decarbonisation of electricity generation, as well as technological advancement in battery technology, so that they can become effective tools in the fight against climate change. If countries do not transition towards renewables and low carbon energy sources, then electric vehicles will continue to be dragged into the “zero emissions” debate.