Is it possible to have sustained economic growth whilst at the same time using less energy and generating fewer emissions? This is the basic question behind decoupling, whereby emissions and economic growth no longer need to go hand in hand.

Although research indicates that global economic growth has finally started outpacing CO2 emissions – data from the Global Carbon Project indicates that this trend has been occurring at double the rate over the past two decades – the feasibility of achieving sufficient decoupling worldwide is unclear, as highlighted in the most recent report from Working Group 3 of the Sixth Assessment by the IPCC, which was published in April 2022.

In fact, a recent report published in The Lancet Planetary Health, also reveals how high-income nations, characterized by their elevated per-capita CO2 emissions, are not managing to reduce carbon emissions in order to fulfill their commitments under the Paris Agreement while simultaneously pursuing overall economic growth at a fast enough pace, calling into question “green growth” claims.

Although research indicates that some countries have managed to achieve a certain amount of decoupling, the degree to which this has been done still leaves them well short of Paris-compliant rates. “At the achieved rates, these countries would on average take more than 220 years to reduce their emissions by 95%, emitting 27 times their remaining 1.5°C fair-shares in the process. To meet their 1.5°C fair-shares alongside continued economic growth, decoupling rates would on average need to increase by a factor of ten by 2025,” reads the Lancet report.

This calls into question recent claims that high income countries can lead the way and places further emphasis on finding solutions to decoupling. So, what are these solutions?

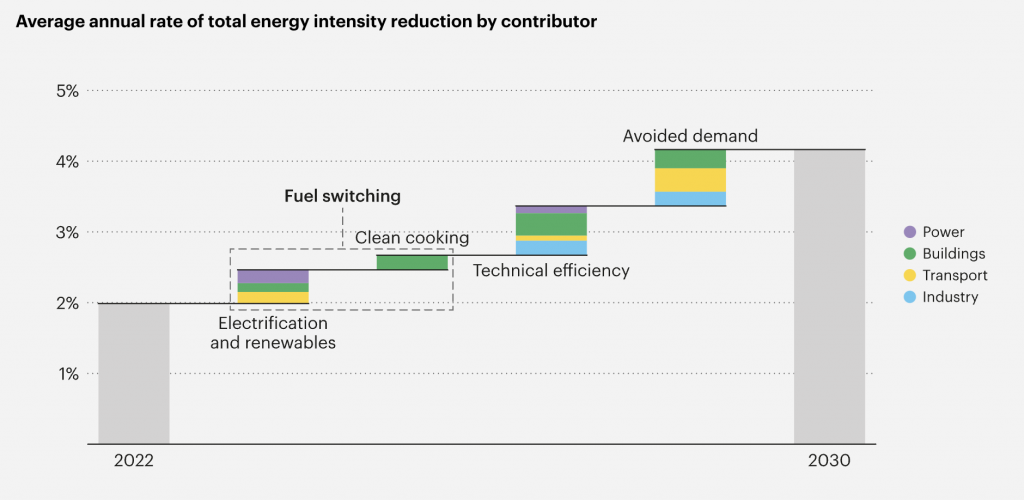

According to the International Energy Agency’ s latest report on how to achieve net zero in the energy sector, scaling up energy efficiency – alongside behavioural change and fuel switching – is one of the key mitigation options available to us which has the potential to double the rate of energy intensity improvements by 2030.

Energy efficiency is therefore seen as the “first fuel” in any clean energy transition as it represents the lowest hanging fruit as the quickest and most cost-effective CO2 mitigation option, which can both lower energy bills and strengthen energy security.

“Together, efficiency, electrification, behavioral change and digitalisation shape global energy intensity – the amount of energy required to produce a unit of GDP, a key measure of energy efficiency of the economy,” reads the IEA report, which also establishes energy efficiency as the single largest contributor to avoiding rising energy demand in the Net Zero Emissions by 2050 Scenario.

Efficient by design

Energy productivity is an indicator of the amount of economic output that is derived from each unit of energy consumed. This means that the energy productivity of a country is measured by dividing national gross domestic product (GDP) by petajoules (PJ) of primary energy consumed. The higher the energy productivity, the greater the energy efficiency.

“Primary energy productivity, the GDP produced per unit of primary energy used, has risen 154% in 7 years but it can raise almost three times that at a third of the real cost,” says Amory Lovins, co founder and chairman Emeritus at the Rocky Mountain Institute, when talking at the Renewable Energy Institute’s event in Tokyo on how to achieve a 100% renewable energy future.

“Across all sectors, integrative design could raise energy productivity by about five fold world wide,” continues Lovins. “Yet, few people think of design as a way to scale rapid change.”

For Lovins integrative design involves “artfully choosing, combining, sequencing, and timing fewer and simpler technologies [which] can save more energy at lower cost than deploying more and fancier but dis-integrated and randomly timed technologies.” Knowing where and when to implement structural changes, such as changing the angle of piping or materials used in building construction, can have massive benefits on efficiency and Lovins sees a design based approach to energy efficiency a starting point to achieving climate goals.

“Optimizing buildings, vehicles and factories as whole systems and not as piles of isolated parts can often make very big energy savings cost less than small savings turning diminishing returns into increasing returns,” he continues.

However, improvements and investments in energy efficiency are still lagging behind the rates required to meet climate goals.

According to the latest market report from the IEA, titled “Energy Efficiency 2022,” investments on a global scale in energy-efficient initiatives, including activities like building renovations, public transportation enhancements, and electric vehicle infrastructure, amounted to USD 560 billion in 2022. This marked a 16% increase compared to the previous year, 2021.

“The oil shocks of the 1970s led to a massive push by governments on energy efficiency, resulting in substantial improvements in the energy efficiency of cars, appliances and buildings,” says IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol during a press conference. “Amid today’s energy crisis, we are seeing signs that energy efficiency is once again being prioritized. Energy efficiency is essential for dealing with today’s crisis, with its huge potential to help tackle the challenges of energy affordability, energy security and climate change.”

The rate of progress

Energy efficiency represents more than 40% of the emissions reduction needed by 2040, as maintaining global growth and supporting development in emerging economies implies a sharp rise in consumption habits. However, energy efficiency in recent years has actually been slowing, with the global rate of improvement falling from 2% in the first half of the last decade to 1.3% in the second half.

In order to align with the IEA’s Net Zero Emission by 2050 Scenario, efficiency enhancements should maintain an annual average of approximately 4% throughout this decade. Although we are seeing positive developments – one out of every eight cars sold worldwide is now electric, and in Europe alone, the number of heat pumps projected to be sold in 2022 is close to 3 million, a substantial increase from the 1.5 million sold in 2019 – the transition to electric-powered transportation and heating are just two pieces of the energy efficiency puzzle, which will require wholesale transformations in the building, transport and heavy industry sectors.

In the building sector, comprehensive energy efficiency renovations play a pivotal role in the decarbonization effort, potentially yielding a more than 50% improvement in energy efficiency per square meter. These changes to buildings, known as “deep retrofits”, are more than just isolated improvements to insulation or heating systems and involve a more integrative approach that also looks at improvements to external and internal structures.

“Integrative design let our retrofit of the Empire State Building save 38% of its energy with a three year payback, making this half century building more efficient than new US offices,” says Lovins.

DYK: Retrofitting is a well-understood practice, and solid building performance data makes it ⬆️ effective. A recent retrofit of New York City’s iconic Empire State Building will cut energy use by 40% and avert 105,000 tons of greenhouse gas emissions. pic.twitter.com/M2tLz3GXi7

— Project Drawdown (@ProjectDrawdown) July 29, 2021

Innovative business models for building refurbishment, are also exemplified in companies such as the Netherlands based Energiesprong, which works towards implementing deep retrofits for entire neighborhoods, capitalizing on economies of scale to enhance cost-effectiveness.

With regards to transport, transitioning the global passenger car fleet to electric vehicles also plays a significant role in advancing net-zero goals. This transition contributes not only by reducing oil demand but also by delivering up to five times greater efficiency compared to conventional vehicles.

EV convert electricity directly into motion which makes them more efficient than conventional cars, which burn fuel (creating heat) and then convert that heat into motion. In fact, electrification in general is seen as one of the prime ways of increasing efficiency across the entire energy sector. “As more energy end uses become electrified, the share of electricity in total final energy consumption increases in the Net Zero Emissions by 2050 (NZE) Scenario from 20% in 2022 to over 27% in 2030,” says the IEA

The industrial sector also presents significant challenges for decarbonization, particularly when considering energy-intensive processes and hard to abate sectors. Discussions on decarbonizing in industry often involve discussion on material efficiency and the adoption of low-carbon technologies and fuels, such as carbon capture and green hydrogen. In fact, reducing energy intensity is crucial, with an estimated emissions reduction potential of around 25-30%, particularly in industries like aluminum, paper, and cement manufacturing.

“The efficiency resource far exceeds the sum of savings by individual technologies,” writes Lovins. “Such ‘integrative design’ is not yet widely known or applied, and can seem difficult because it is simple, but is well proven, rapidly evolving, and gradually spreading. Yet the same economic models that could not predict the renewable energy revolution also ignore integrative design and hence cannot recognize most of the efficiency resource or reserves.”

Climate protection, with energy efficiency at its core, hinges on the urgent acceleration of its progress. The key to success lies in recognizing and harnessing the full spectrum of efficiency potential. To achieve this, the emphasis should shift away from concentrating solely on individual technologies and instead focus on comprehensive systems encompassing buildings, factories, vehicles, and the broader systems in which they operate.