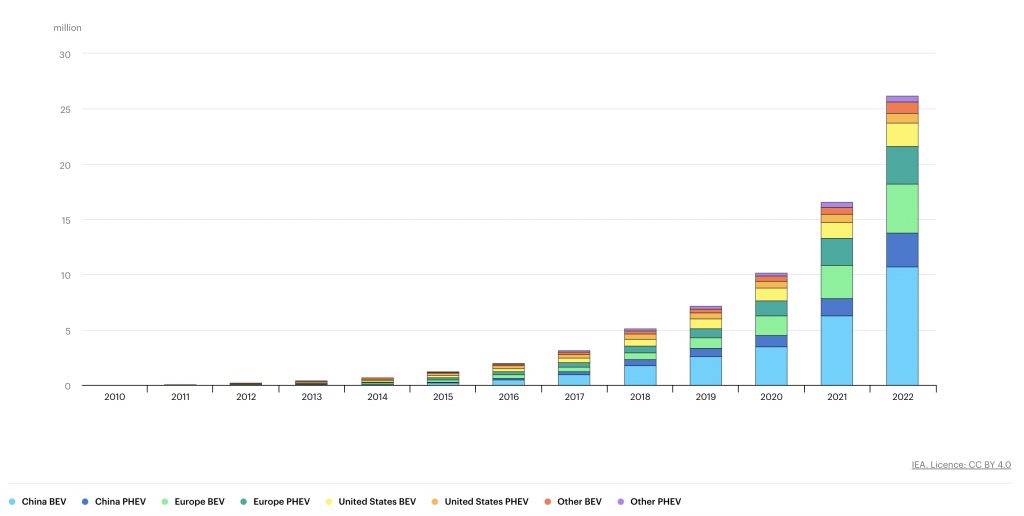

Electric cars have shifted gears and moved out of the world of sci-fi inspired futures. Thanks to a combination of early adopters and government handouts they have grown beyond initial predictions. According to the International Energy Agency the total sale of electric cars has more than tripled in three years, from around 4% in 2020 to 14% in 2022. In June 2023 global plugin vehicle registrations were up 38% compared to June 2022, amounting to approximately 19% share of the overall auto market.

“There’s not a car company that’s not investing significantly in electrifying its offerings to the tune of a trillion dollars globally. That is a once-in-a-century transformation of a major sector that is happening, present tense,” says former EVgo CEO Cathy Zoi, on the Resources for the Policy Leadership Series Podcast.

As electrification in the transport sector is no longer a thing of the future researchers are looking into what the impacts of this transition are, what pieces are missing to further accelerate change, and what future growth and gains from this process might be.

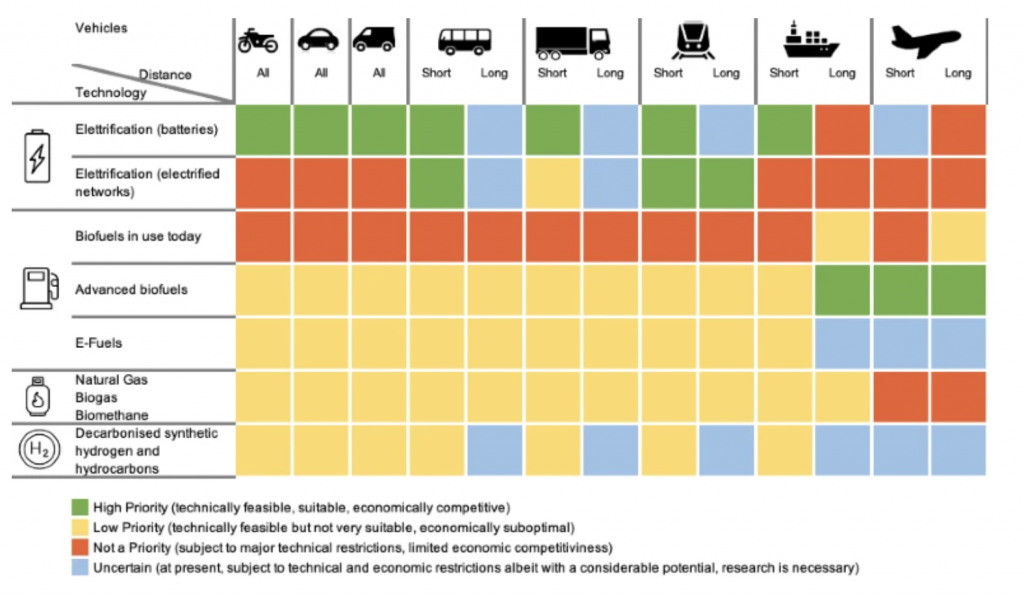

Recent studies have signaled out direct electrification as the most promising technological option for decarbonisation, with strong growth prospects particularly in light vehicle road transport.

Authors of the report “Decarbonising Transport. Scientific evidence and policy proposals” published in April 2022 – among which Carlo Carraro, Professor at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice and member of the CMCC Strategic Board and Massimo Tavoni, Professor at Politecnico di Milano and Director of the RFF-CMCC European Institute on Economics and the Environment – claim that: “Already with the current energy mix, the replacement of the above internal combustion vehicles — which today represent over 99% of Italian road transport — with electric vehicles would lead to a 50% reduction in emissions from light road transport. An even deeper decarbonisation would be obtained by increasing the share of electricity produced from renewable sources.”

The report highlights the great potential of electrified transport but also some of the barriers, incluging the need to shift towards renewable energy sources.

A 2021 paper published in Environmental Research Letters, also confirmed the need to couple electrification with a shift away from fossil fuels for full gains in decarbonization to be met. “Transport electrification without the replacement of fossil-fuel power plants leads to the unfortunate result of increasing emissions instead of achieving a low-carbon transition,” reads the report. “With technological innovations such as electrified road transport, climate change mitigation does not have to occur at the expense of economic growth. Because a transport electrification policy closely interacts with energy and economic systems, transport planners, economists, and energy policymakers need to work together to propose policy schemes that consider a cross-sectoral balance for a green sustainable future.”

Slow progress

Notwithstanding the potential gains there are still considerable barriers to achieving decarbonization in the transport sector. Since 2010 transport emissions have been rising at a faster rate than in any other end-use sector and in 2023 they amount to about 23% of global-energy related CO2 emissions. 70% of those emissions come from road transport.

Even in Italy where overall greenhouse gases emissions have actually decreased over the past three decades – due to a mixture of technological improvements, energy policies and slow economic growth – the transportation sector’s emissions are still 3.2% above 1990 levels.

When it comes to electric vehicles some of the rising concerns are high costs for both the vehicles and electricity prices, as well as ongoing concerns about charging infrastructure. According to The Economist’s latest research on EVs “the biggest problem is price. After factoring in limited supply and high manufacturing costs associated with the lithium-ion batteries used in EVs, the upfront cost of a battery-powered car is up to 40% higher than that of an internal combustion engine (ICE) car. With the exception of China, where EVs have reached price parity with ICE cars, most consumers are still reluctant to make the switch.”

The main concern seems to be a slowdown compared to initial growth predictions in Western countries. EVs are predicted to account for 38% of new car sales in 2027, as opposed to the 67% that had been forecasted previously in the United Kingdom, and similarly in the US new EVs registered on the road rose by 1.3% in the final quarter of 2023, which was well below the 15% rise between April and June.

Part of the slow progress in the UK is down to the government suspending handouts for consumers, one of which was a 5,000GBP electric-car grant that was initially reduced and then removed completely in 2022.

In response the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (smmt), called for more incentivesfor consumers, citing the 50,873 GBP cost of a typical ev as 40% more expensive than a new petrol or diesel car. According to the smmt incentives such as reducing vat on EVs for three years could help increase the EV fleet by 270,000 vehicles.

Fuelling the transition

To propel the decarbonization of the transportation sector the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report, published in April 2023, established mitigation options that align the sector with the Paris Agreement objectives.

One of the most talked about is vehicle to grid (V2G) integration. Since AR5, integrating electric utility grid operations with electric vehicles to both reduce range anxiety – the worry on the part of a person driving an electric car that the battery will run out of power before the destination or a suitable charging point is reached – and at the same time manage electric grids.

“V2G has been characterized as a comparatively advantageous means of peak load shaving, assuming peak shaving events lasted one hour or less per day,” reads the IPCC report

In China extensive measures have been taken to enable V2G systems. “China’s state planner has issued new rules on strengthening the integration of new energy vehicles with the electric grid, as the world’s biggest market for electric vehicles (EVs) aims to manage its power demand amid a transition to renewable energy,” reads a recent Climate Home News article.

Brattle Group analyst Ryan Hledik also told Climate Home News that charging during off-peak hours should make EV use cheaper and therefore more widespread. But he warned that vehicle to grid technology and its business case are still in their infancy.

Legislation

The European Union and the United States have passed legislation to match their electrification ambitions. The European Union adopted new CO2 standards for cars and vans that are aligned with the 2030 goals set out in the Fit for 55 package. In the United States, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), combined with adoption of California’s Advanced Clean Cars II rule by a number of states, could deliver a 50% market share for electric cars in 2030, in line with the national target. The implementation of the recently proposed emissions standards from the US Environmental Protection Agency is set to further increase this share.

According to Massimo Tavoni, co-author of the Nature report, “Direct electrification is the best option to reduce environmental impact and improve energy security. How this electrification will occur also depends on different areas of the transport sector.

For example, “for local public transport, in particular at city-level, battery-powered vehicles represent the best choice in terms of infrastructure, pollution and emissions reduction. For extra-urban transport, extended-range battery-powered vehicles compete with hydrogen-fuel-cell vehicles.”

What the report shows with clarity – and hence also reflecting the findings of the latest IPCC Report – is that we now have the means to reduce emissions in the transport sector so that they are aligned with our climate goals. However, “The process will be fully successful only if accompanied by a conversion of the industrial sectors connected to the transport system, currently largely focused on the internal combustion engine and fossil fuels. This entails active labour policies, opening new value chains, promoting circular material practices and introducing social measures to ensure an equitable transition.”

When talking about the impact of policy choices on electrification in the transport sector one must talk about China. According to the IEA China accounted for nearly 60% of all new electric car registrations globally, and in 2022 the People’s Repubblic registered over 50% of all the electric cars on the world’s roads, a total of 13.8 million.

“This strong growth results from more than a decade of sustained policy support for early adopters, including an extension of purchase incentives initially planned for phase-out in 2020 to the end of 2022 due to Covid-19, in addition to non-financial support such as rapid roll-out of charging infrastructure and stringent registration policies for non-electric cars,” treads the IEA report.

In the meantime binding targets for zero-emission sales for car companies are one of the main sources of optimism for the sector’s transition. For example, new laws that oblige 22% of carmakers’ sales in Britain to be electric have just come into force and the target is set to increase to 100% by 2035. Although the transition may be a little slower than previously anticipated it seems that there is no room for a u-turn.