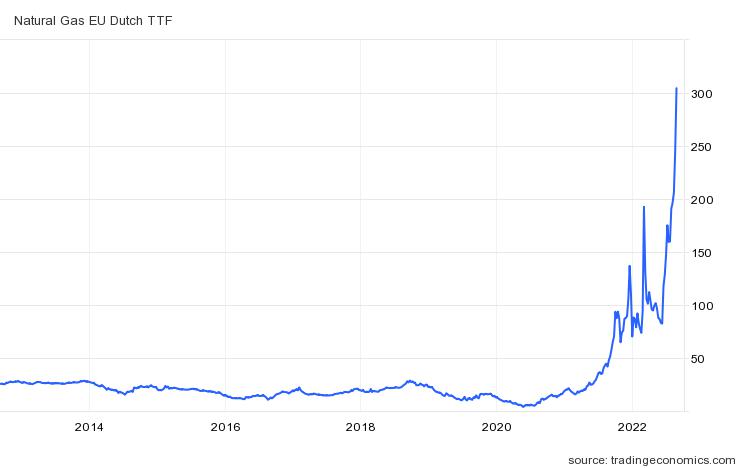

With the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the resulting economic sanctions, oil and gas prices have experienced a vertiginous rise bringing with them inflation, pushing price indexes through the roof and leading to an energy crisis in Europe and beyond.

Analysis from think tank Ember reveals that these rises in prices are driven almost entirely by reliance on fossil fuels. And not just in Europe, which is heavily reliant on Russian natural gas for their energy supply. Across the globe inflation is causing concern leading to talks of recession and economic crisis.

In the UK alone inflation has reached 10%, largely due to a reliance on Russia for 4% of its gas, 9% of its oil and 27% of its coal. Even more worryingly, the European Union relies on Russia for 40% of its gas, approximately 27% of its imported oil and 45% of its coal.

However, the intrinsic link between the unfolding crisis and an overreliance on fossil fuel imports has also led some experts to posit that this represents a unique opportunity to overhaul energy systems and push countries towards doubling down on clean energy, not only for environmental reasons but also for energy security.

Sarah Brown, senior analyst at Ember, told The New European that: “Public opinion has massively turned so governments aren’t frightened of saying domestic renewables are the answer […] The argument that renewables are less reliable, that’s blown out the window. Any argument that they could possibly be more expensive has been blown out the window. The argument that fossil fuels offer security of supply? Gone.”

Opportunity in crisis

It isn’t unprecedented for rising energy prices to boost the development of alternatives to dominant energy sources. Most recently, the Opec oil crisis in the 1970s brought a monumental shift in approaches to energy efficiency and the first real boost to large scale renewable energy infrastructure. A clear historical example of rapid transition and what people, communities and governments can do when mobilized to act.

“If you look across the energy system and across history, simple economics tells you that if you have a higher fuel price, consumers will change, whether that’s from oil or from natural gas,” explains Michael Cohen, chief U.S. economist and head of oil analysis at BP, when interviewed by Politico. “If there are alternatives, then consumers will change.”

Although the 1973 oil crisis didn’t bring an end to the fossil fuel paradigm today there is a new factor in play: a deeper understanding of climate change. “If the industry was already facing a metaphysical challenge in climate change, it’s now got a second [with the war in Ukraine],” says Mark Brownstein, senior vice president at green group Environmental Defense Fund, which works with the industry to cut its greenhouse gas emissions.

However, some believe that the crisis could actually inhibit renewable energy development leading to a rush to build more fossil fuel infrastructure in an attempt to bring down prices and boost supply, locking the world into “irreversible warming” and potentially creating a mass of stranded assets.

Chevron Corp Chief Executive Michael Wirth told Reuters that Europe’s plan to double down on renewable fuels in response to rising fuel costs may actually have the unintended short-term effect of increasing prices and slowing down the energy transition.

“That can erode the public support that will be necessary for the energy transition,” explains Wirth. “One of the things I worry the most about is a period of high prices that voters begin to identify with energy transition ambitions.”

Wirth went on to call for policy choices that incentivize carbon emission reductions instead of putting a cap on oil and gas supply before renewable fuels, such as solar and wind power, are able to replace fossil fuels on a large scale. One mechanism Wirth advocates for is a pricing mechanism for carbon in the United States similar to the one set in Europe.

Europe feels the burn

As one of the areas most impacted by rising prices of oil and gas, due to a large reliance on Russian imports, the European Union is facing a turning point in its energy policy.

Although the bloc had already taken important steps in the direction of clean energy with the adoption of the European Green Deal, which requires the bloc to cut emissions by at least 55% by 2030, natural gas originally featured heavily as a transition fuel. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has put this strategy in question, as natural gas prices continue to soar.

According to the opinion piece by Alfonso Medinilla, head of climate action and green transition at the ECDPM think tank, “The EU is rethinking the pace of its own transition in the face of crisis and taking extraordinary measures to undo Europe’s risky dependence on Russia.”

Russia has cut back its supply of gas through the Nord Stream 1 pipeline, which is particularly concerning as winter nears and demand for energy will rise. This has led to some EU countries declaring that they may turn to coal to overcome the predicted energy shortfall.

German economy Minister Robert Habeck told Reuters that the country was forced to take a “bitter” decision to restart idle coal power plants but it was a “sheer necessity” to cut gas use.

Although commission officials claim that these will only be short term stopper measures there is fear that this will further delay a move towards clean energy.

In March, the EU said it would slash Russian gas dependency by two-thirds this year and put a stop to its reliance entirely well before 2030. To do this, it drafted REPowerEU, a €210bn plan to accelerate the Green Deal.

The plan outlines how renewable energy will make up 45% of the EU’s energy needs by 2030 – up from around 22% in 2020. This will mean speeding up the approval process for wind and solar farms and calls for solar panels on all commercial buildings by 2026 and on residential buildings by 2029.

Not all is green

Yet reactions to the crisis have, thus far, not all been green. Oil industry company Shell has been asked to boost its gas production in the North Sea and in Germany it is in talks to take over one of the most important refineries if Russian gas were to be cut off.

In a Financial Times interview, Shell chief executive Ben van Beurden explains that governments had too often set emissions goals without a plan of how to achieve them and pushed for cuts in oil and gas production without taking measures to curb consumer demand. “As long as society believes that by starving [fossil fuel] supply you will somehow force demand to come down as well, that is not a sustainable way of tackling the energy transition. Supply needs to adjust but it needs to adjust to less demand.”

On a similar note the secretary-general of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries told CNBC Arabia that the oil sector needs $12 trillion worth of investments in the years up to 2045 to make up for the current shortfall and bring down crude oil costs.

This comes in stark contrast to the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report which shows how existing and planned fossil fuel projects will push the world beyond 1.5 °C. Further boosting fossil fuel production as a response to the current energy crisis is therefore a clear recipe for climate disaster.

Mark Radka, head of the UN Environment Programme’s (UNEP’s) Energy and Climate Branch, also explains how the rise in renewable energy can help contrast the current energy crisis.

“The premise that if you move too quickly away from fossil fuels, you will reduce your economic means of combating climate change is an odd logic. The costs of the energy transition will not be small. But the costs of inaction far exceed the costs of taking action. We need energy, but we also need a healthy climate for the planet to function: we need an energy transition that is climate compatible.”