Cop26 president Alok Sharma told reporters on Tuesday following the release of the COP26 Draft Agreement: “We are making progress at Cop26 but we still have a mountain to climb over the next few days.”

The breakthrough moment of negotiations in Glasgow, after over a week of intense negotiations, came with the release of a first draft of the COP26 deal. Although it has been greeted with a mixed reception from observers and experts one of the most notable aspects is its implicit acknowledgement that current pledges are insufficient to avert climate catastrophe and hence requests that countries “revisit and strengthen” their targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions up to 2030 by the end of next year.

The UK Presidency has this morning published the #COP26 first draft cover decisions

I will be holding an informal stocktaking plenary at 1230 today

We will continue to hear all views and my door is open to everyone

👇

Documents | UNFCCC https://t.co/6JcXAQ4OBW

— Alok Sharma (@AlokSharma_RDG) November 10, 2021

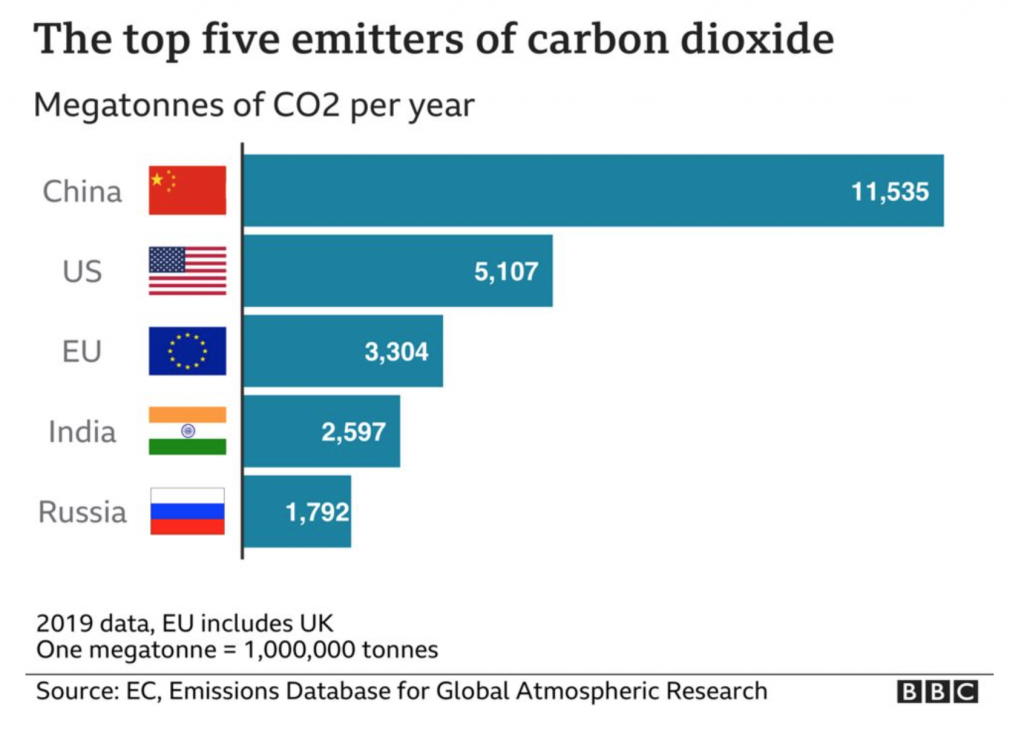

The other significant development came later in the day when China’s lead negotiator Xie Zhenhua announced that the world’s top two greenhouse gas emitters, the US and China, who account for about one-third of total emissions, were releasing a “China-US joint Glasgow declaration on enhancing climate action in the 2020s”.

This was followed shortly after by the American envoy, John Kerry, who went on to confirm that both countries would commit to keeping the increase in the Earth’s mean surface temperature to “well below” 2℃, and ideally to no more than 1.5℃, compared with pre-industrial levels — reiterating the Paris agreement pledge from six years ago.

China and the US see eye to eye

What is so significant about the China-US joint declaration? According to The Economist, “The statement acknowledges that current efforts are inadequate, and so the duo promised to work together to narrow the gap between their emissions-reduction plans and what science says is necessary to meet the Paris goals.”

This includes a pledge from China to begin phasing out its coal consumption during the five years from 2026-30 and cutting emissions of the powerful greenhouse gas methane.

According to the BBC, the joint declaration is a “rare” occurrence and that there was agreement on “a range of issues including methane emissions, the transition to clean energy, and de-carbonisation.”

Furthermore, considering tensions between China and the US in recent weeks, with Biden signalling out the failure of Xi Jinping to attend negotiations in Glasgow, the joint statement indicates that there is a possibility for collaboration and multilateralism, which will be essential in addressing the climate crisis.

In fact, the joint statement also included explicit references to how the two nations will collaborate, including on research, policies to produce energy without carbon and efforts to reduce methane emissions and ban illegal deforestation.

“Together we set out our support for a successful COP26, including certain elements which will promote ambition,” explained Kerry when speaking about the deal between Washington and Beijing. “Every step matters right now and we have a long journey ahead of us.”

This signals a return to previous efforts to collaborate when Xi Jinping and former President Barack Obama agreed to share research and development of low-carbon technologies in 2015 in the build-up to the 2015 climate summit in Paris.

EU climate policy chief Frans Timmermans voiced his belief that the U.S.-China agreement gave room for hope.

“It’s really encouraging to see that those countries that were at odds in so many areas have found common ground on what is the biggest challenge humanity faces today,” he said. “And it certainly helps us here at COP to come to an agreement.

I welcome today's agreement between China and the USA to work together to take more ambitious #ClimateAction in this decade.

Tackling the climate crisis requires international collaboration and solidarity, and this is an important step in the right direction. #COP26

— António Guterres (@antonioguterres) November 10, 2021

With the joint statement, both sides have shown an understanding that there is a substantial gap between the efforts of countries to limit emissions to date, and what science says is necessary to curb the worse effects of climate change. Whether the plans to bridge that gap are sufficient is another matter and remains to be seen.

A draft of what is to come

The COP26 draft agreement was also announced on November 10, with parties calling for stronger carbon-cutting targets by the end of 2022. The draft also acknowledges the need for more help for vulnerable nations. Although the text has already come under fire been for not being ambitious enough, others have been receptive to its focus on the 1.5C target.

The first major step in rising ambition is that nationally determined contributions (NDCs) must be update next year at COP27 in Egypt, instead of in five years, as originally laid out in the Paris agreement.

According to The Economist, another major step forward is how the draft calls on all countries “to accelerate the phasing-out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuels”, though it fails to mention any dates. Nevertheless, that is a bigger step than it sounds when you bear in mind that the Paris agreement does not even contain the words ‘fossil fuels’.”

However, Climate Change News reports that “Strong pushback is expected from countries with big coal, oil and gas interests like Australia and Saudi Arabia.

“The inclusion of coal phaseout language in the draft follows more than 40 countries signing a statement promising to phase out coal in the 2030s for major economies and 2040s for developing countries. But several members had little coal to start with, while big miners and consumers like Australia, China, Japan and India did not join. At least two signatories, Poland and South Korea, later backtracked on the pace of the transition.”

Finally, the draft also puts significant emphasis on the need to pursue the lower 1.5°C temperature goal of the Paris agreement. The document “recognizes that the impacts of climate change will be much lower at the temperature increase of 1.5 °C compared to 2 °C and resolves to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C.”

One of the key goals of the British presidency was to “keep 1.5C alive” so the strong language in the draft is what many countries were hoping for notwithstanding the firm opposition by countries such as Saudi Arabia, Russia, China, Brazil and Australia.

The draft “recognizes that limiting global warming to 1.5 °C by 2100 requires rapid, deep and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions, including reducing global carbon dioxide emissions by 45 per cent by 2030 relative to the 2010 level and to net zero around mid-century,” using language that is in line with the latest UN climate science report.

However, the strong wording on 1.5C does not hide the fact that: “current pledges in Glasgow are not even close to meeting these cuts by 2030. If countries do not start straight away on a path towards these 2030 emission levels it will be too late to update them in 2025,” explains William Collins, professor of meteorology at the University of Reading, when talking to CNN.

Even if fully implemented, 2030 climate pledges and policies would result in 2.4C, according to analysis by Climate Action Tracker. This figure narrows to 2.1C when binding long term targets are counted and 1.8C in the most optimistic scenario.

Finally, another major shortcoming of the draft agreement revolves around the crucial issue of climate finance. The draft looks at this aspect with strong language: “[The conference] notes with serious concern that the current provision of climate finance for adaptation is insufficient to respond to worsening climate change impacts in developing [countries].”

However, it fails to state exactly when the $100 billion should be delivered, only indicating 2023 as the cut-off date, which is three years past the deadline agreed upon in Paris. Observers have pointed out that for the Paris goals to be achieved emissions reductions will be required from all countries, including low-income ones, and that without strong financial support, the Paris agreement could fail.

“On one side of the scales, [the draft text] advances a detailed process for accelerating climate mitigation goals, but, on the other side of the scales, on finance and loss and damage, it is fuzzy and vague,” said Mohamed Adow, director of Power Shift Africa.

Here's how the #COP26 text falls short:

*No clear goals on adaptation

*No clear process to help the world deal with #LossAndDamage

*Does not address failure by rich nations to deliver $100bn@mohadow speaks @CANIntl event pic.twitter.com/IMrFAdulYq— Power Shift Africa 🌊 (@PowerShftAfrica) November 10, 2021

The document is not final and COP26 delegates from nearly 200 countries will now negotiate the details over the next few days. However, it is worth noting that in the past draft COP agreements have been watered down in the final text, although there is also a chance that some elements could be strengthened, depending on how negotiations develop.

What is certain is that COP26 is just one step in a long process and that calling it a failure or a success doesn’t encompass the complexity of the negotiation process that spans over months and years and not just in the few weeks in which global leaders come together.

According to Carbon Brief: “The reality is more nuanced. There has been progress made in flattening the curve of future emissions through both climate policies and falling clean energy costs. At the same time, the world is still far from on track to meet Paris Agreement goals of limiting warming to 1.5C or “well below” 2C.”