Volatility in oil prices, mixed with increasingly aggressive legislation that makes fossil fuels less attractive for investors, is driving the transition to a new energy paradigm. Long accused of being too expensive and non-competitive, the global market is finally opening its doors to renewables as an economically viable solution to our climate related predicaments. However, “without shifts in policy there is unlikely to be a clean energy revolution”, explains Shayegh Soheil, scientist at RFF-CMCC European Institute on Economics and the Environment (EIEE), whose recent research paper maps the interaction between market structures and government policies aimed at supporting the transition to clean energy.

Capital markets are shifting and clean power could generate up to 45% of energy by 2024. Policymakers across the globe are backing the transition with measures that range from near-zero interest rates for clean energy developers to Green New Deals that focus on decarbonisation. Not to mention that a Joe Biden presidency, will come with 2 trillion USD investments in decarbonising the US economy.

Furthermore, the strong stimulus measures being put in place to counter the effects of the COVID pandemic are also being deployed with green strings attached. In Europe, around 30% of the 880 billion USD COVID recovery plan is being tied to climate measures. In fact, European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen has confirmed the EU’s goal of cutting greenhouse-gas emissions by 55% over 1990 levels by 2030, indicating that reforming the energy sector is a vital part of this process which will require strong policy efforts.

The role of government policy

Understanding how governments can facilitate the transition is an area of new and intense research. “For any game changer technology, the biggest player is the government because the government doesn’t have to think about cost and benefit in the same way as private investors do. It can instead focus on the long term impact on society. In this sense, the government is solving a different problem from private investors. The private and public have a very different mind-set and the private sector will probably tend to invest in less risky and more mature technologies,” explains Soheil.

New research, published in the Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews journal, indicates that the relationship between clean energy policy choices and the market conditions in which these policies are deployed is extremely important in determining the effectiveness of said policies. “If the government policy is to increase the market share of renewables, then how this broader policy interacts with the market structure (whether it is a regulated, deregulated or semi-regulated market) is extremely important. These policies have to be connected to the kind of market in which you are implementing them. We found that market structure influences the effectiveness of policies”, explains co-author of the paper Soheil.

📢𝗡𝗲𝘄 𝗽𝗮𝗽𝗲𝗿 𝗮𝗹𝗲𝗿𝘁📢https://t.co/S3fmbmkjRI

Can 𝗱𝗲𝗿𝗲𝗴𝘂𝗹𝗮𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻 help bring down the cost of 𝘀𝘂𝗯𝘀𝗶𝗱𝗶𝗲𝘀 to achieve a certain market share (𝗥𝗣𝗦 mandate) for 𝗿𝗲𝗻𝗲𝘄𝗮𝗯𝗹𝗲 energy technologies? It depends!@Dan_L_Sanchez @EIEEorg @Unibocconi pic.twitter.com/yTuZUupMSb

— Soheil Shayegh (@soheilsh) October 12, 2020

The two main policies used by governments to encourage renewable energy development can be labelled as Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) and, Feed in Tariff (Fit) which is more popular in European countries. The main difference is that with RPS governments mandate a certain share of the market to be supplied by renewables (for example, setting 50% of the electricity market to be provided by renewables by 2050). On the other hand, with FiT the strategy is more about governments fixing prices which in turn encourages energy producers to enter the market and develop renewable energy.

Soheil explains that, “it is not enough to just think about policy, countries need to consider the market conditions in which they are implementing their strategies. The best match between policy and market conditions is important and market conditions can encourage or discourage certain kinds of policies.”

For example, Germany has used FiT to promote renewable energy and this has attracted a lot of renewable energy generators. Over the last few years, more generators and producers of renewable energy have joined the program which has driven down the price of renewable energy generation below the threshold that the government set in the FiT policy. Since the government has guaranteed a certain price, it has forced it to pay more than it should for the renewable energy being produced. This creates what is known as a financial burden.

Bringing about a 40% reduction in emissions by 2030 requires, for example, that low-emissions sources provide nearly 75% of global electricity generation in 2030 (up from less than 40% in 2019), and that more than 50% of passenger cars sold worldwide in 2030 are electric (from 2.5% in 2019)

International Energy Agency

In contrast, a drawback of RPS is that it doesn’t specify what kind of renewable energy you are favouring which in turn creates competition between renewable energies and therefore more mature sources with lower production costs will have an upper hand, nipping the development of other promising but more expensive technologies in the bud.

Francesco Lamperti, scientist at the European Institute on Economics and the Environment (RFF & CMCC), also believes that “there is strong evidence that lots of technologies in the initial phase are funded with public funds through grants or subsidies. All these public programs that stimulate investments are also capable of creating employment in green jobs which are in turn skilled jobs that generate more productivity. However, these benefits are only visible in the mid to long term. Policies that can support long term investment plans that can direct the transition towards certain technologies and create stable long term conditions so that the private sector can enter when the risks, from a technological point of view, are already absorbed by the public sector. Because the investor that can afford to take on large losses is the state.”

Just as governments are putting together their Covid response strategies there is a unique chance to provide a strategic vision and adequate funds for an energy transition. Governments can spur innovation to provide incentives for consumers and favour action by the private sector. Research such as that led by Soheil can provide invaluable information in determining what kinds of policies to adapt based on the market conditions in which they are being deployed.

The current situation

A special report by The Economist indicates that investment in renewables is still drastically short of where it needs to be to keep temperatures within 2°C of pre-industrial levels. Yearly investment in wind and solar capacity needs to be about 750 billion USD, which amounts to three times recent levels. With strong measures, renewable electricity such as solar and wind could rise from the current 5% of global energy supply to 25% in 2035, and nearly 50% by 2050.

Renewables 2020 is out!

This new @IEA report shows renewable power is still growing strongly despite the Covid crisis – unlike all other fuels.

Renewable electricity generation will rise 7% in 2020, & capacity additions will set records this year & next https://t.co/bDABjXgQVx pic.twitter.com/MFXx5sovqk

— Fatih Birol (@IEABirol) November 10, 2020

To date, the energy sector remains the largest single emitter of greenhouse gasses due to its reliance on burning coal, natural gas, and oil for electricity and heat. Just as emissions have increased by 40% over the past 30 years, reaching the objectives set out in the 2015 Paris Agreement will require a 90% fall from current levels over the next 30 years. No mean feat, particularly as global population is projected to rise by 2 billion over the same time period and global GDP is expected to triple.

With the world still producing over 4/5 of its energy using fossil fuels, there is a huge opportunity to cut emissions by enacting a paradigm shift in the way we produce energy. Yet the opportunity that is unfolding also comes with huge challenges. Not least of which economically: the International Energy Agency (IEA) claims that this transition will require 1.2 trillion USD of extra annual investment in the power system alone.

The renewable energy market

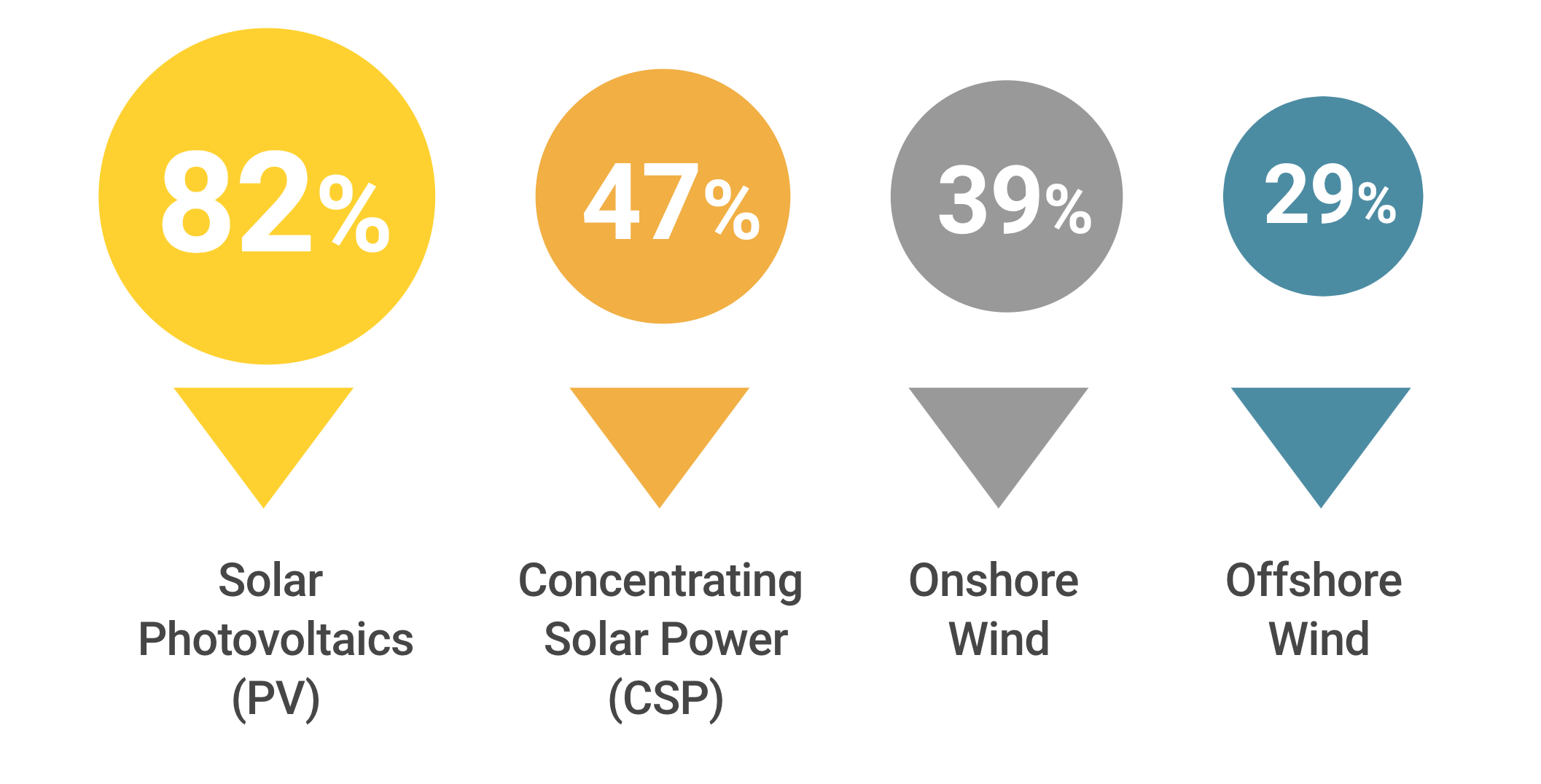

Newly installed renewable power capacity is increasingly more cost-effective than the cheapest power generation options based on fossil fuels. The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) also confirms this trend in its latest study that shows how more than 50% of renewable capacity added in 2019 had lower electricity generation costs than coal. “New solar and wind projects are undercutting the cheapest of existing coal-fired plants”, outlines the report.

Solar photovoltaics have seen the most pronounced reductions in costs of production over the last decade with an 82% decrease, followed by concentrating solar power (CSP) at 47%, onshore wind at 40% and offshore wind at 29%.

The economic advantages of transitioning to clean energy are huge. “Replacing the costliest 500 gigawatts of coal capacity with solar and wind would cut annual system costs by up to USD 23 billion per year and yield a stimulus worth USD 940 billion, or around 1% of global GDP.”

According to Ramiro Parrado, Scientist at the CMCC’s Economic Analysis of Climate Impact and Policy, “From the point of view of power generation, the costs of renewable energy have been decreasing fast. This has led to an increase in their share of final energy consumption and, at the same time, attracts more investments in the renewable sector. This trend will continue in the future and trigger a transition where the economy will rely much more on renewable energy sources instead of fossil fuels.”

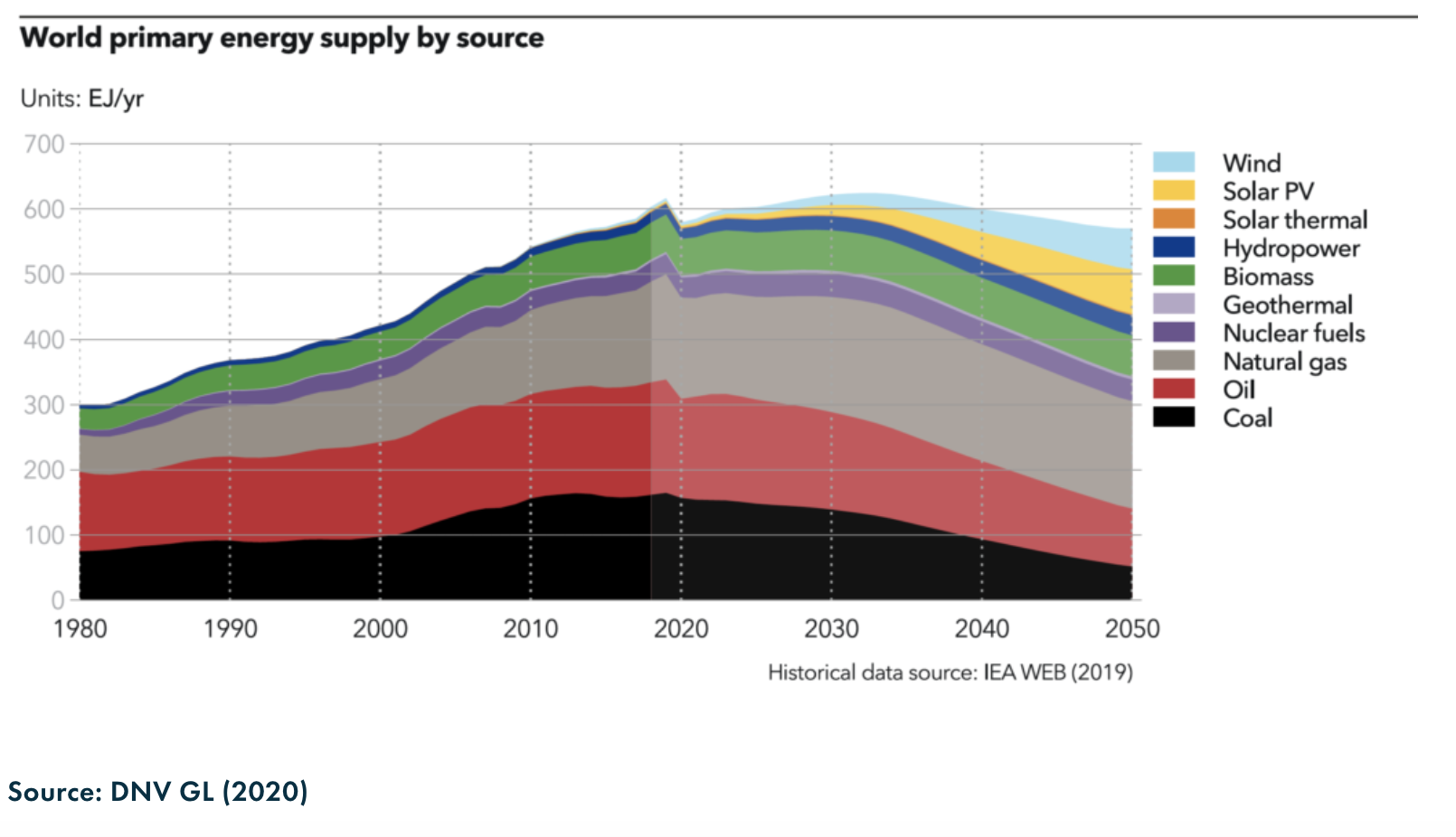

Researchers are increasingly pointing to 2020 as a breakwater moment, the DNV GL’s 2020 energy outlook report (which gives an independent model based forecast of the world’s most likely energy future) reports that 2019 was the peak of the fossil fuel era; and research by the Renewable Energy Agency indicates that renewable energy generation is increasingly competitive and less expensive than fossil fuels.

A fossilized energy system

Over 80% of the global energy supply is currently taken from fossil fuels, which in turn leads to the energy sector being the single largest emitter of greenhouse gasses: around 2/3 of total emissions. Yet the problems related to fossil fuels are not just limited to the effects they have on the environment and our wellbeing, with pollution from their combustion believed to lead to approximately 4 million premature deaths per year (most of which in the developing world’s mega-cities).

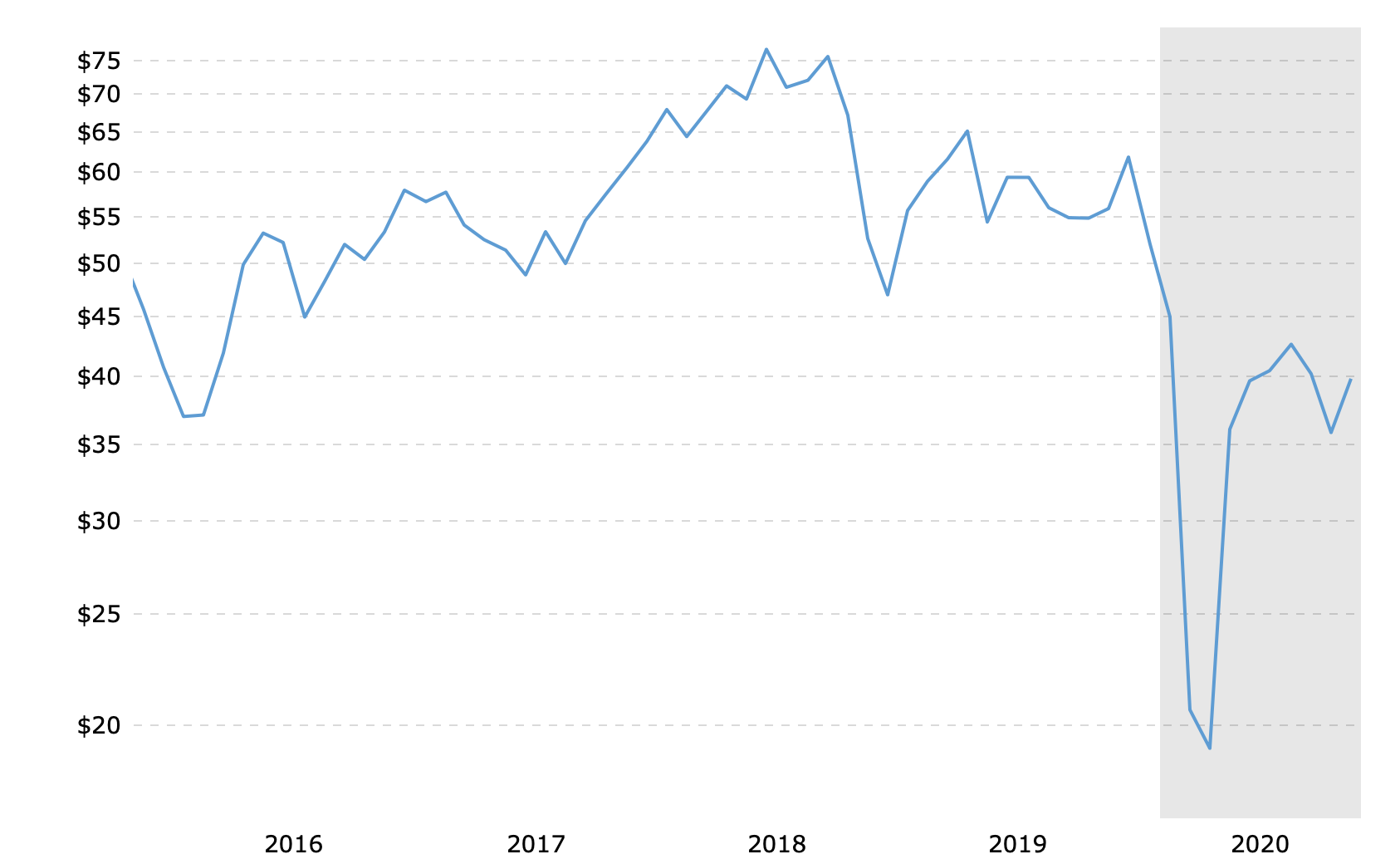

Fossil fuels tend to concentrate in specific geographic areas making supply chains vulnerable which leads to political and economic instability. The most well documented example is that of oil, the price of which has varied by over 30% in a 6-month time span 62 times since 1970.

This price instability was once more exposed during the COVID pandemic which has affected the global economy even more than the 2008 financial crisis. A collection of 7 of the world’s most prominent oil producers lost almost 90 billion USD in value of their fossil fuel reserves since the beginning of 2020 as global demand for oil has taken a strong hit. The think tank Carbon Tracker found that Royal Dutch Shell, BP, Total, Chevron, Repsol, Eni and Equinor decreased their oil and gas assets by 87 billion in the last 9 months alone, with 55 billion USD coming in the latest financial quarter.

Their research also indicates that loss in value had already started before the pandemic due to government efforts to cut back on emissions which led to companies indicating they would depend less on oil and gas in the future and shift their focus from the energy sector to the petrochemical and plastics sector.

How has COVID affected the clean energy revolution

The IEA’s World Energy Outlook (WEO) report gives a detailed assessment of the effects of the pandemics on a clean energy transition. According to all scenarios outlined in the WEO, renewables will grow in the coming decades with solar energy becoming the fastest growing source. This is both thanks to favourable policies and advancements in technology that make entry into markets more advantageous.

Solar in particular has seen exceptional cost reductions over the last ten years, making it currently cheaper than most coal or gasfired power plants. In some cases, solar energy has become the cheapest electric energy in the world. In one policy scenario outlined in the WEO, in which Covid-19 is gradually brought under control in 2021 and the global economy returns to pre-crisis levels that same year: “renewable energy generation meets 80% of the growth in global electricity demand to 2030. Hydropower remains the largest renewable source of electricity, but solar is the main driver of growth as it sets new records for deployment each year after 2022, followed by onshore and offshore wind.”

Without shifts in policy there is unlikely to be a clean energy revolution.

Shayegh Soheil

Although established renewables such as wind and solar are showing resilience in the face of the current pandemic there are some who are concerned about the future of less mature technologies that have the potential to become game-changers.

“Due to COVID and the financial costs of recovery programs incurred by governments to help small businesses, families and public health, the support for renewables could decrease. As government subsidies for renewables may decrease due to these other financial commitments, only mature renewables such as solar and wind could survive. This means a possible long delay in commercialization of higher-cost technologies with greater decarbonization potential that are still in research and development phase”, explains Shayegh Soheil, scientist at RFF-CMCC European Institute on Economics and the Environment (EIEE).

Has oil demand reached its peak?

The DNV GL’s 2020 energy outlook predicts that COVID will have a permanent effect on fossil fuels and that 2019 was the year of peak oil demand. BP, one of the UK’s leading oil and gas companies, also forecasts that demand will peak early this decade.

"Nothing short of a wholehearted embracing of the energy transition will be enough," says @Accenture's Muqsit Ashraf, who speculates that the point of peak oil demand may already be behind us.

Read his recommendations for oil companies: https://t.co/zCsJKQyQGe

— Climate Solutions Lab (@ClimateSolLab) November 10, 2020

Peak demand will have huge consequences on a financial market that was predicting decades of growth. “Peak demand means overcapacity and low prices, it means stranded assets and stranded companies, it means a restructuring of the old and a bright new world of opportunity for the new. A glance at the underperformance of the energy sector over the last few years shows that investors are well aware of the rising risks,” claims Kingsmill Bond, Energy Strategist for Carbon Tracker.

The International Energy Agency also confirmed a trend of falling demand for the energy sector as a whole in its World Energy Outlook 2020 Report claiming it had shrunk by around 5% in 2020 and an 18% decrease in investment. However, what is interesting when talking about an energy transition is that “the impacts vary by fuel. The estimated falls of 8% in oil demand and 7% in coal use stand in sharp contrast to a slight rise in the contribution of renewables. The reduction in natural gas demand is around 3%, while global electricity demand looks set to be down by a relatively modest 2% for the year.”

Here's a remarkable detail buried in @IEA #WEO20

India will build 86% less new coal power capacity than expected last yr

Long seen as driving global coal growth, IEA now says India will add just 25GW by 2040

The result? Global coal capacity will fall.https://t.co/bt7QfouTAf pic.twitter.com/SUDlaMo8so

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) October 15, 2020

However, the IEA is slightly less optimistic when it comes to peak demand of oil and links the future of renewables to policy. “The era of growth in global oil demand is predicted to peak within ten years, but the shape of the economic recovery is a key uncertainty.”

A bright future

As everyone is focusing on the immediate impacts of the Covid pandemic it is also important to look at what the long term effects will be. How will this crisis change the next ten years in terms of policymaking? “There has been a paradigm shift and now the issue of global challenges like public health and climate change are intertwined. Even if governments are more constrained financially, there is also a lot more public support for climate related policies,” remarks Soheil who conducted a recent survey on COVID that returned a very interesting and unexpected result: climate change was still the number one worry of many respondents notwithstanding the pandemic.

Maintaining a strong pace of emissions reductions post-2030 will depend on a focus on energy and material efficiency, electrification, and a strong role for low-carbon liquids and gases. “Bringing about a 40% reduction in emissions by 2030 requires, for example, that low-emissions sources provide nearly 75% of global electricity generation in 2030 (up from less than 40% in 2019), and that more than 50% of passenger cars sold worldwide in 2030 are electric (from 2.5% in 2019)”, outlines the IEA.

Promisingly, the current share of renewable energy is better than what most scenarios predicted in 2018, with renewables set to overtake coal as the world’s largest source of power by 2025, outpacing the “accelerated case” set out by the IEA just a year ago. The IEA’s 2018 predictions on solar have also been beaten: with a 40% larger output and 20-50% cheaper cost of generation than previously thought.

With oil producers taking heavy hits and a structural decline in coal use underway there is an unprecedented opportunity. However, achieving net-zero emissions will entail changes in more than just the energy sector.