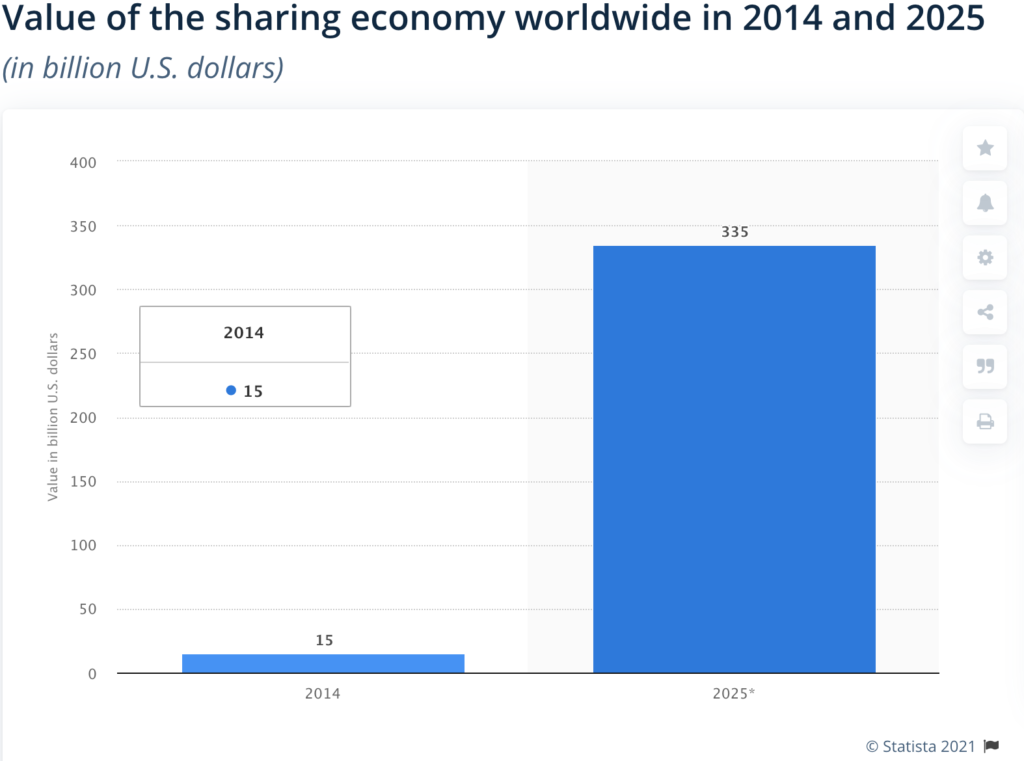

Technological advancement has gone hand in hand with the growth of the sharing economy whereby digital connections allow for the creation of networks and facilitate sharing. Today sharing services such as Uber, Airbnb, Craigslist and Zipcar – just to name a few – play a significant role in the global economy, with the total value of the global sharing economy predicted to increase to some 335 billion U.S. dollars by 2025, from only 15 billion U.S. dollars in 2014.

A sharing economy involves making goods and services available to individuals and groups so that the physical assets become services. In theory this increases the use value that can be gained from any given good and enables people and organizations to earn profits from underutilized resources. This economic model differs from traditional businesses, whereby goods and services are owned by a single owner and then rented to the public.

Ideas of increased efficiency and maximising the value of goods has led to the sharing economy being considered a positive contributor to lowering emissions and decreasing man’s carbon footprint. Often associated with the circular economy proponents posit that the sharing economy can help us continue to take advantage of the comforts of having certain goods (such as a car or a house at the seaside) without having to own these goods.

On the other hand, the sharing economy has also come under fire for its ability to evade government regulations and hence gain an unfair advantage over traditional businesses. The most well known example is that of uber. Numerous countries have started to regulate Uber – thus raising licensing and staffing costs – so as to put them on a level playing field with traditional taxi services.

Furthermore, recent studies have started to indicate that the environmental gains of some sharing services are not as clear cut as might seem and that initial perceptions of the sharing economy may have been overly optimistic in their analysis of the role it can play in resolving climate issues and lowering emissions of certain sectors (such as that of transport for example).

From car sharing to Airbnb

Participation in sharing economy services can lead to changes in consumer behaviour, including mobility and vehicle ownership patterns, which could in turn have positive environmental benefits. A recent study looks at how the emissions of an average car sharing member in the United States change by considering total mobility-related greenhouse gas emissions reduction related to business-to-consumer car-sharing participation. A comprehensive model which takes into account distances travelled annually by the major urban transport modes as well as their life-cycle emissions factors and which reveals: “a significantly more modest reduction of the annual total mobility-related life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions caused by car-sharing participation has been estimated, 3–18% for three geographical case studies investigated (versus up to 67% estimated previously).”

In particular, one of the innovative aspects of the study was to look at the changes in car use lifetimes due to sharing and the overall impact that this has. This reveals that whereas sharing practices are frequently advertised and perceived as being inherently more sustainable over private ownership, this should not be taken as a given and that there are a variety of “rebound effects” that could curtail initial benefits and which need to be addressed in future research so as to improve the sustainability of sharing services.

In a similar approach, a new study has looked at the carbon footprint of Airbnb hosts in Sydney. By modelling four different scenarios, the study posits that the induced carbon footprint of Airbnb hosts ranges from 3.84 to 602 kg CO2e/room-night. These findings challenge the conclusions presented by many previous studies that highlight the positive effects of the sharing economy in decreasing environmental impacts.

The main difference associated with this study is that it chooses to also address indirect and induced carbon footprint which includes the spending of surplus income on the purchase of “additional goods and services to improve customer service for their guests, and to improve their own living standards.” Another issue taken into consideration is the use of electricity and gas in houses that would have otherwise been left vacant. Although these factors can be hard to calculate including them in future studies can help gain a more detailed picture of the overall impacts of the sharing economy.

The sharing economy is here to stay

Both studies are not a denouncement of the sharing economy as environmentally unfriendly but simply challenge the notion that sharing is inherently sustainable. Through this kind of research and by problematizing the issue researchers can help improve the sustainability of the sharing economy.

Undoubtedly sharing has helped lower emissions, with a 2017 study indicating that “shared services in urban environments have helped offset the potential increase in greenhouse-gas emissions by about 3% since 1960, the study found.”

“The sharing economy and peer-to-peer platforms can be set up in a way that they incentivize this simultaneous sharing of resources and can drive down emissions, and I think it can be a good thing for sustainable cities,” says the paper’s co-author Anthony Underwood of Dickinson College in an interview with The Post. However, he also emphasises that adequate policies and regulations must also follow.