The most effective way of tackling anthropogenic climate change involves bringing down global carbon emissions. This means that countries not only need to lower emissions on home soil, but also ensure that these aren’t simply shifted elsewhere. Furthermore, countries implementing strict environmental policies are looking for ways to protect themselves against unfair competition from countries with less ambitious carbon regulations.

Carbon border adjustments are seen as a way of providing protection for countries that are transitioning to less carbon-intensive ways, whilst providing an incentive for industry players across the globe to lower emissions.

However, this approach has been met with opposition, not least from countries such as China and India, who argue that it amounts to protectionism, violates trade principles and is incompatible with World Trade Organization (WTO) rules.

“More than the issues of compliance with international trade rules, that remains a matter of great complexity, the main barriers to carbon border adjustments are the huge challenges of practical implementation related to their computation and administration costs,” explains CMCC researcher and co-director of the European Institute on Economics and the Environment (EIEE) Francesco Bosello.

Carbon border adjustments around the world

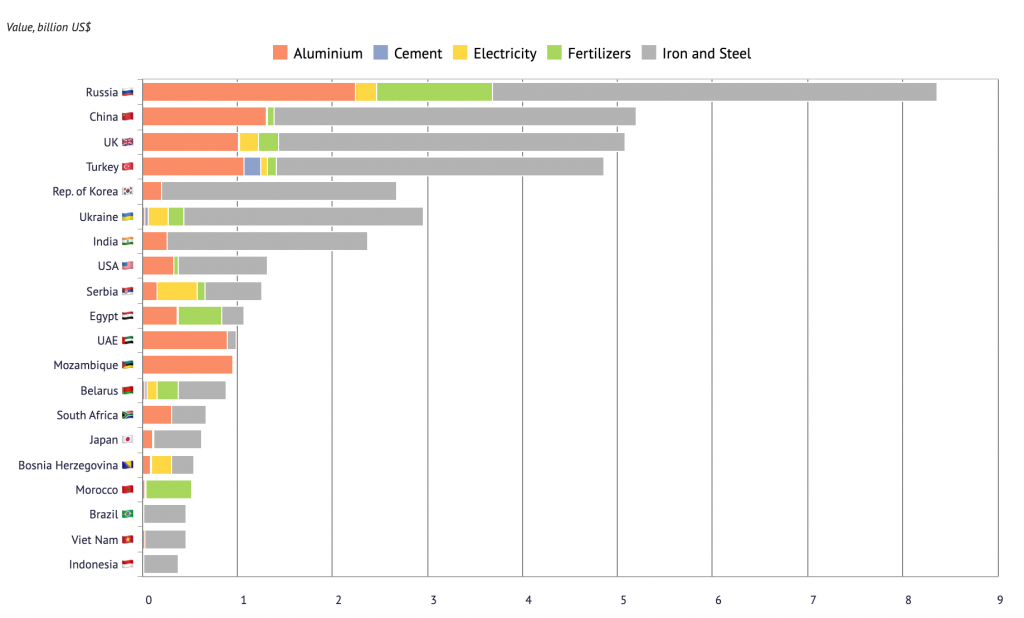

In July 2021, the European Commission proposed a carbon border adjustment mechanism to tackle help protect European industry from unfair competition. In its initial phase the mechanism establishes a carbon price on imports of certain products in an effort to support domestic industry players that will be affected by higher carbon prices compared to foreign competition.

Furthermore, the mechanism is also designed to ensure that everyone is rowing in the same direction, and that European emission reductions will also contribute to a global emissions decline, instead of simply moving carbon-intensive production outside Europe, a phenomenon that is known as “carbon leakage”.

Although the European proposal is the first of its kind on such a large scale, carbon border adjustments are not just limited to the EU. In the USA, the state of California has already used the mechanism to regulate electricity imports, making electricity importers liable for the emissions associated with electricity generated by states outside of California.

Furthermore, discussions are starting to take place at a federal level, pushed by the Biden Administration, with a carbon border fee bill that would be similar and interlinked with the European one. “There’s a real prospect that Canada, E.U. and U.K. all basically bind together on a common carbon border adjustment. And if we haven’t joined up with them, we’re just sort of deliberate losers,” explained Senator Sheldon Whitehouse in an interview with Climatewire.

How do they work?

Carbon border adjustments are an emerging set of trade policy tools that seek to curtail high emission economic activity from moving out of countries or economic areas with relatively strict climate policies and into those with more lenient ones.

“They work by applying corrective prices on imports based on their carbon content in an effort to cover potential price differences that arise due to emissions reduction policies such as those being implemented in the EU,” explains Bosello.

Typically, carbon border adjustments also include tax rebates so that domestic producers who have to adhere to high environmental standards are not at a competitive disadvantage in foreign markets.

Also known as border carbon adjustments, carbon border adjustment mechanisms (CBAM) or border tax adjustments, they have gained particular notoriety since the EU announced that it would launch its CBAM as part of the European Green Deal and in an effort to update its Emissions Trading System (ETS), which is its current instrument of choice for regulating carbon emissions within the trading bloc.

“The agreement in the Council on the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is a victory for European climate policy. It will give us a tool to speed up the decarbonisation of our industry while protecting it from countries with less ambitious climate goals,” says Bruno Le Maire, French Minister for Economic Affairs, Finance and Recovery when talking to the European Council.

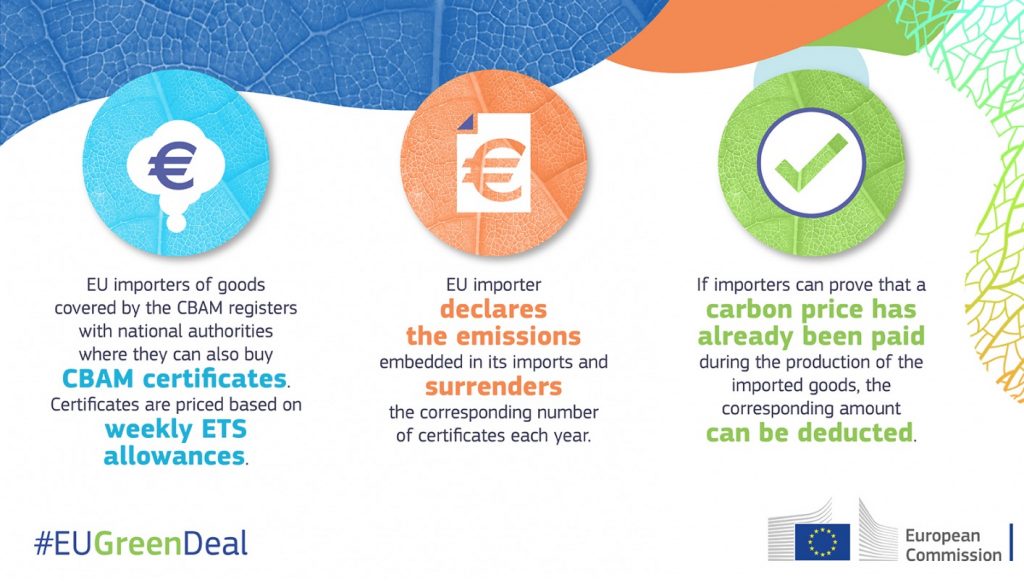

Under the EU’s CBAM EU importers will purchase carbon certificates that are in line with the carbon price that would have been paid, had the goods been produced under the EU’s carbon pricing rules. Whereas the ETS sets a cap on the amount of greenhouse gas emissions that can be generated by industrial players in given sectors, CBAM will apply to direct emissions of greenhouse gasses emitted during the production process of the products covered.

“In the EU today, carbon leakage is handled by handing out free emission allowances to some industries. This system is heavily criticized for not being efficient, thus the Commission wants to replace it with a BCA,” says Trade Policy Adviser, Fredrik Gisselman, in his Carbon Border Adjustment report.

Although the CBAM is designed to safeguard the efficacy of the bloc’s carbon pricing system it is believed that it can also propel other countries into emissions reductions and lead to the coordinated implementation of more carbon border adjustments.

The idea is that adjustments can increase the environmental effectiveness of climate policies, by providing disincentives for economic activity that may cause higher total greenhouse emissions. Furthermore, they ensure that industry players in countries with strict environmental regulations remain competitive and don’t move production abroad so as to avoid costly emissions reductions.

However, just how effective CBAM measures will be remains an issue of contention. “Economic analysis indicates that there is no clear-cut evidence on the effects of CBAM. For instance, in a recent study conducted at the European Institute on Economics and the Environment (EIEE) in collaboration with Resources for the Future and RITE we show that CBAM can be indeed effective in reducing adverse competitiveness effects against EU energy-intensive sectors. However, they are less effective in ‘convincing’ countries with less stringent climate targets to increase the ambition of their mitigation policy. For that, other types of agreements should be reached. Therefore, the aim and scope of CBAM should be clear and limited,” explains Bosello.

Pros and cons

On the one hand, carbon border adjustments may create a level playing field for international trade and climate policy by putting a price on carbon. They are a way of ensuring that low emissions do not come at the cost of competitiveness and allow countries and blocs such as the EU to continue with ambitious climate policies whilst not putting their own industry players at a disadvantage or or leading to carbon leakage.

Furthermore, by charging tariffs on imports countries will also raise money which can then be spent on other environmental policies. For example, the EU’s CBAM, which is set to go into effect in 2023, may raise up to €5 billion and €14 billion in revenue each year. The EU claims that this will then be used to cover export rebates, invest in climate mitigation and resilience technologies, and even be distributed to citizens in the form of a dividend.

On the other hand, the implications that these measures have for free trade and the issues involved in the technicalities of implementing them have gone under scrutiny. In fact, the larger the pool of products that come under a carbon adjustment mechanism the more the organizational difficulties and costs will rise.

“What are the big challenges? The first one is political. But after that, there are legal, technical, and administrative challenges […] There are literally thousands of greenhouse gas–intensive products traded in the international markets and hundreds of nations. And the rules keep changing, the policies keep changing, markets evolve. So any system you impose will have some serious administrative challenges,” says international climate policy expert Brian Flannery when talking on the Resources for the Future Podcast.

Not only will it be hard to collect all the information necessary to price imports appropriately but the veracity of the information may be hard to verify.

Finally, the challenges to diplomacy implicit in carbon border adjustments cannot go overlooked as they threaten not only to undermine trade agreements but also to put a spanner in the works of climate policy. The solution to this seems to hover around the question of what type and breadth of emissions to include and what industries to target.

“It is fully possible to design a carbon border adjustment that is in compliance with WTO rules,” says Gisselman. “But such a measure is very complex and it needs to be very carefully designed to be efficient and in compliance with WTO law. Two of the most difficult issues to solve are how to take other countries’ climate policies into account and if export rebates for EU companies may or should be included.”

As the BCAs move from the realm of the theory to practical implementation, as the EU’s CBAM demonstrates, more research will be required to see that they are implemented in an effective way as well as to determine how good they are at curbing emissions whilst providing a level playing field.

Furthermore, the issue of climate justice also needs to be considered as carbon border adjustments are likely to impact less developed countries, that are less able to implement emissions reductions, than wealthier nations that have a greater margin for investing in emissions reductions.