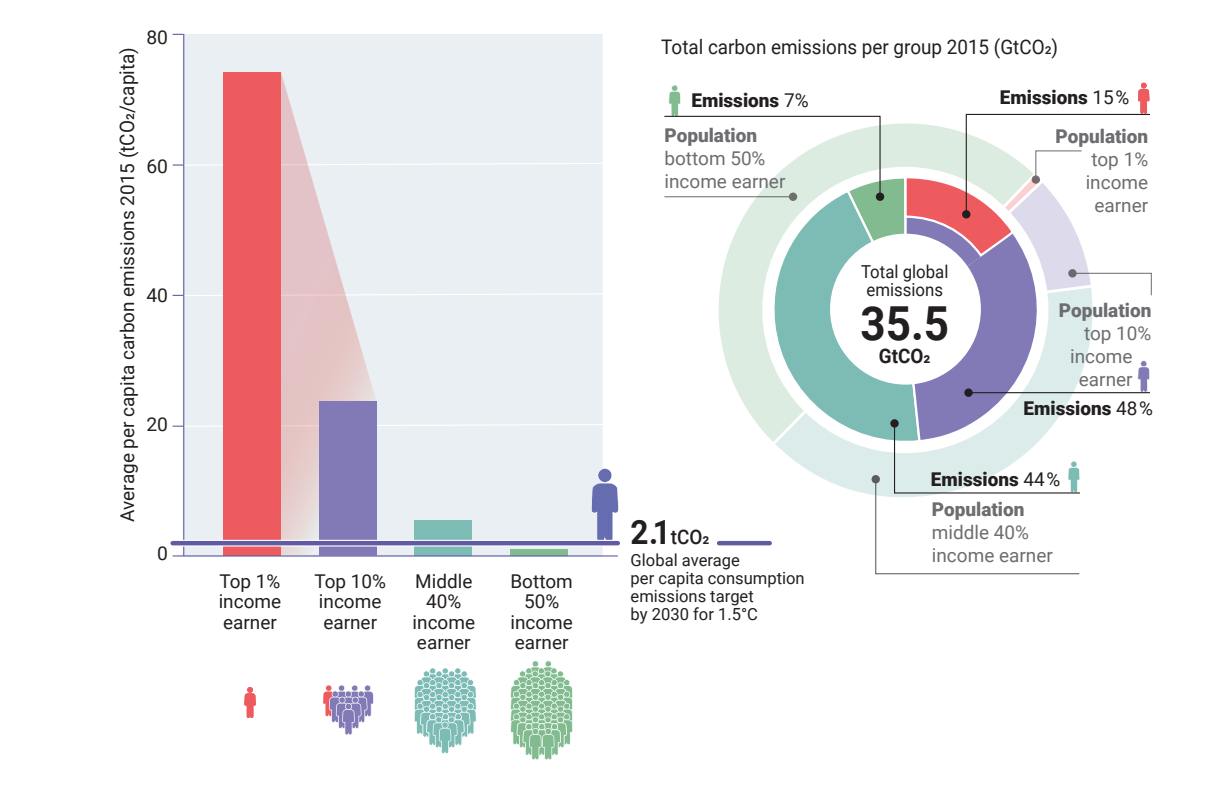

Not all impacts of climate change are felt equitably among people and communities. What is more, not everyone is equally responsible for these changes. Climate justice starts from the recognition of these two base principles and has developed into an important component of discussions on climate change adaptation and mitigation.

The classic example is that of small island states whose very existence is threatened by changing weather patterns and rising sea levels. Countries like Tuvalu in the Pacific, and Antigua and Barbuda in the Caribbean are facing existential risk whilst having contributed little to rising emissions and hence climate change. How should this knowledge inform and influence climate policies? This is one of the core concerns of climate justice.

Furthermore, as climate change threatens to exacerbate existing inequalities and widen the gap between advantaged and disadvantaged communities – countries that will swim and those that will sink – there is an even greater need to develop effective solutions and reshape the debate on how to tackle climate change, integrating strategies on how to cut emissions with an approach that also takes the needs, rights and inequalities of human society into consideration.

Deconstructing climate justice

The term climate justice was popularized in the 1990s by activists from the Global South who were seeking to place the burden of responsibility for climate change on wealthy and powerful nations, whilst demonstrating that the poorest nations are also those most affected by a changing climate and the need to lower emissions.

This legacy persists in more modern conceptions of the term, whereby the idea that rich countries should be held accountable for historical emissions remains intrinsically linked to the climate justice term and movement.

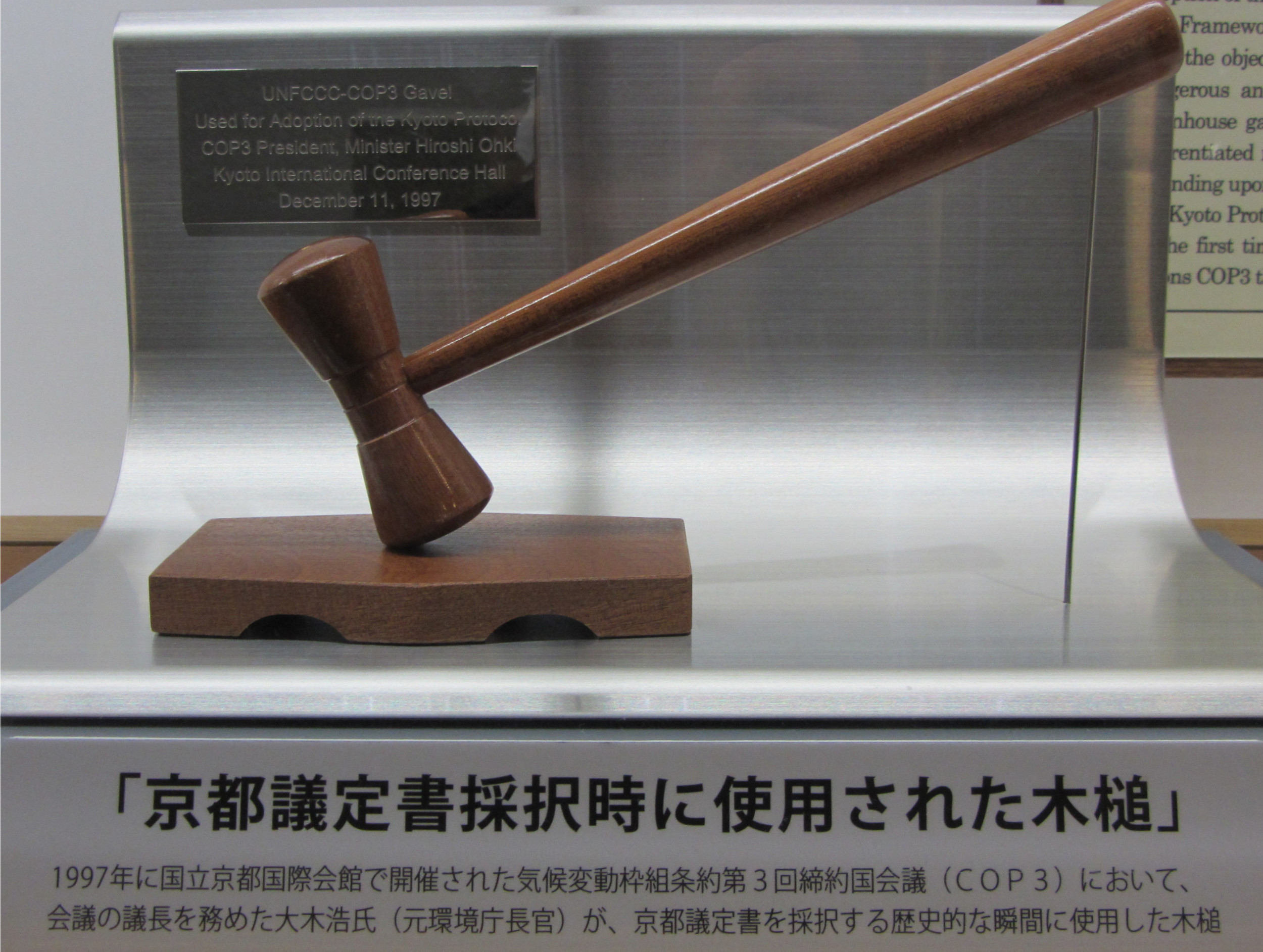

In an implicit act of recognition of differentiated responsibility for climate change, high-income countries even agreed to provide up to 100bn USD per year by 2020 to support adaptation and mitigation strategies in low-income countries at the United Nations climate summit in Copenhagen in 2009.

This figure has since become a key area of contention in climate negotiations such as COP26, as industrialized countries have thus far failed to stay true to their promise, eliciting the indignation of representatives from developing countries.

A matter of rights

Linking the issue of causes and effects of climate change to one of rights, ethics and politics – rather than purely environmental or physical factors – is increasingly entering the realm of academia and policymaking, informing policy decisions that lead to more equitable approaches to tackling the climate crisis.

For instance, the bridging of human rights and climate change is already happening at both a local and global scale with numerous national governments, the United Nations (UN) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) all recognizing that climate change is “not borne equally or fairly, between rich and poor, women and men, and older and younger generations.”

The two latest instalments of the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) also include specific references to climate justice. In particular, the February 28 Working Group II Report – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (WGII), puts the spotlight on the inequalities which make certain communities and countries more vulnerable to climate change impacts than others.

Climate justice comprises justice that links development and human rights to achieve a rights-based approach to addressing climate change.

Sixth Assessment Report WGII

The WGII Report defines climate justice in the context of three principles: “distributive justice which refers to the allocation of burdens and benefits among individuals, nations and generations; procedural justice which refers to who decides and participates in decision-making; and recognition which entails basic respect and robust engagement with and fair consideration of diverse cultures and perspectives.”

It also goes on to establish with high confidence that integrated and inclusive system-oriented solutions based on equity and social and climate justice reduce risks and enable climate resilient development. Therefore not only highlighting the need to support vulnerable communities but also the benefits that this could bring to sustainable development.

In the process, the IPCC also takes care to frame climate justice as the coming together of development and human rights, to achieve a rights based approach to addressing climate change.

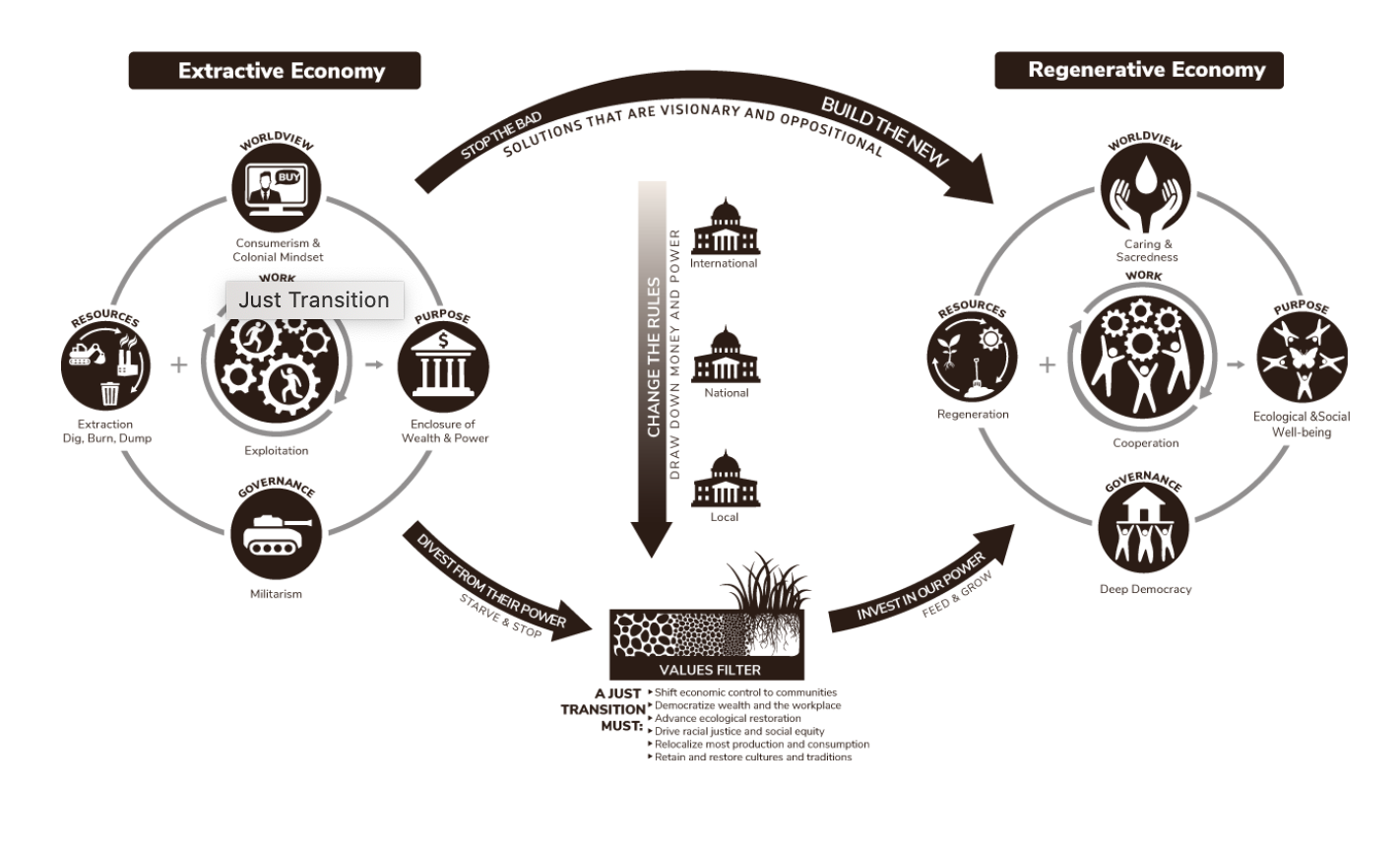

A process that is also being driven by civil society organizations such as Climate Justice Alliance that works to unite frontline communities and organizations to deliver a “just transition away from extractive systems of production, consumption and political oppression, and towards resilient, regenerative and equitable economies.”

Climate justice is not solely a question of national responsibilities, encompassing issues of race, gender and class. Not to mention the intergenerational issues associated with burdening future generations with the environmental and social consequences of our current actions.

The process of linking climate justice to human rights has therefore been ongoing. Such as the first Climate Justice Summit – held in the year 2000 just as the COP6 negotiations were taking place in The Hague – where climate change was repeatedly linked to the concept of human rights. Or the Bali Principles of Climate Justice – developed in 2002 by a coalition including CorpWatch, Third World Network, Oil Watch, the Indigenous Environmental Network, among others – where activists sought to redefine climate change from a human rights and environmental justice perspective.

Establishing a legal grounding

The link between human rights and climate justice is a powerful one as it also allows vulnerable groups to use the legal system to challenge governments and corporations to take responsibility for their emissions and impacts on the environment.

When speaking to Carbon Brief, legal specialist at the London School of Economics and Political Science, Dr Joana Setzer explains that: “Courts have the mandate to consider how action or inaction on climate change affects legally protected interests, such as human rights. In some cases, bringing a court proceeding can allow activists and others to force a debate on how legal obligations to protect those interests should be implemented, even in the face of stagnation or opposition in the political process.”

In fact, the UNEP Global Climate Litigation Report: 2020 Status Review, outlines how climate cases nearly doubled between 2018 and 2021 causing governments and corporations to improve their approaches to climate issues.

Recent trends in climate litigation include “greenwashing” and non-disclosures, when corporate messaging contains false or misleading information about climate change impacts.

Learn more in the new report on climate change litigation.#ClimateCrisishttps://t.co/XT06KkIRy5

— UN Environment Programme (@UNEP) January 26, 2021

Successful cases include the 2020 Neubauer et al vs Germany case, in which a group of German youth challenged the German Federal Climate Protection Act, stating that its target of reducing GHGs 55% by 2030 from 1990 levels was insufficient and therefore a violation of their human rights.

Not to mention the 2019 case raised against the fossil fuel corporation Shell – by the environmental group Milieudefensie/Friends of the Earth Netherlands and co-plaintiffs – that claimed Shell’s contribution to climate change violated its duty of care under Dutch law and human rights obligations.

A just transition

Climate justice is therefore not solely about making past wrongs right but also about building a better future and ensuring a just transition, which is defined by the Climate Justice Alliance as “a vision-led, unifying and place-based set of principles, processes and practices that build economic and political power to shift from an extractive economy to a regenerative economy.”

This means approaching production and consumption cycles in a holistic manner that is both just and equitable, whilst ensuring that no one is left behind in the transition to a low carbon economy.

The idea of a just transition is enshrined in the Paris Agreement and has also been embraced by policymakers around the world, such as in the European Commission’s Just Transition Fund.

The green transition will only be successful if everyone benefits from it. The Just Transition Fund Will actively support the changes leading to a thriving and socially fair climate-neutral economy.

Commissioner for Cohesion and Reforms, Elisa Ferreira (Just Transition Fund Press Release)

An essential part to ensuring a just transition involves taking into account both the international implications of climate justice and human rights. For this to take place effectively there has to be an evolution in the study of the concept, with some researchers advocating for a more holistic approach where climate justice is delivered in union with the pursuit of other justice claims.

It is clear that climate justice will play an increasingly important role in future activism, policy debates and even academia. Issues such as the COVID pandemic will also serve to increase the need to implement a just transition that leaves no one behind, offering key lessons for the realm of climate policy as well.