Imagine a future where heatwaves and droughts are ravaging the Earth. Where ecosystems are irreversibly degraded, and climate change has drastically altered society. Being able to place ourselves in other peoples’ shoes is central to human imagination and understanding the consequences of our current actions on future generations.

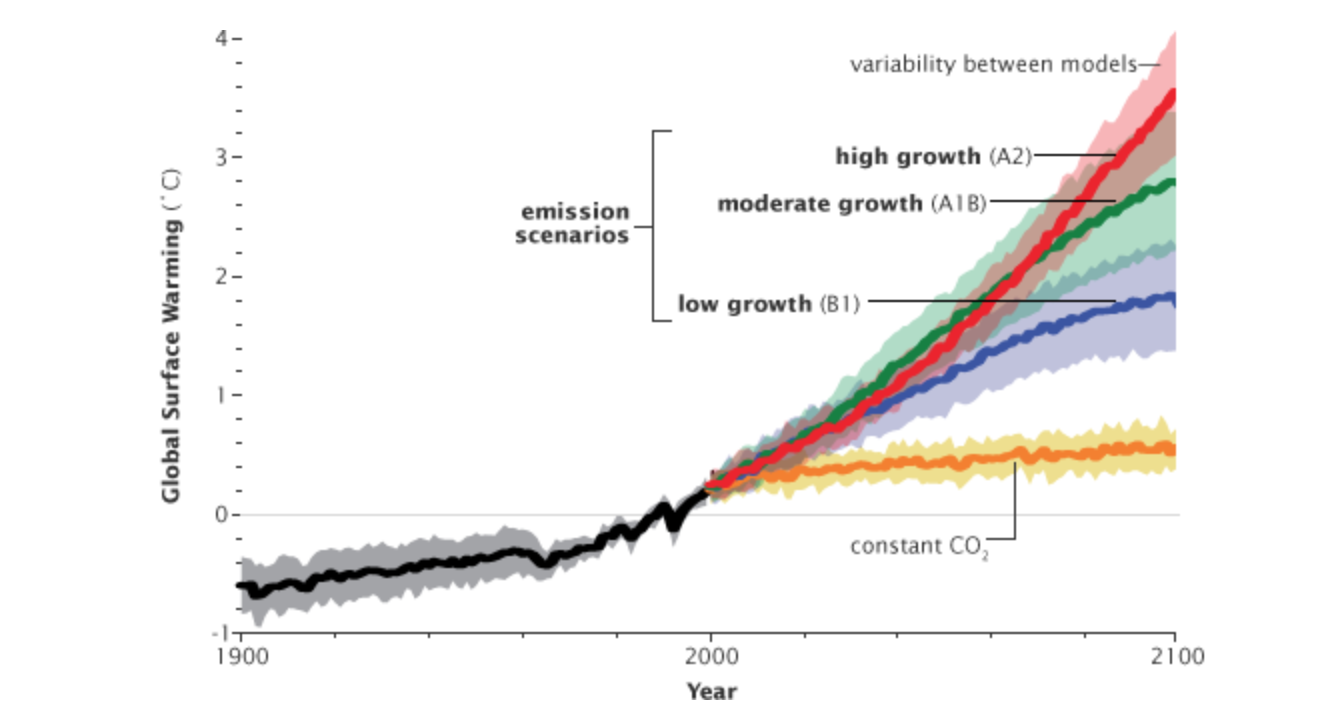

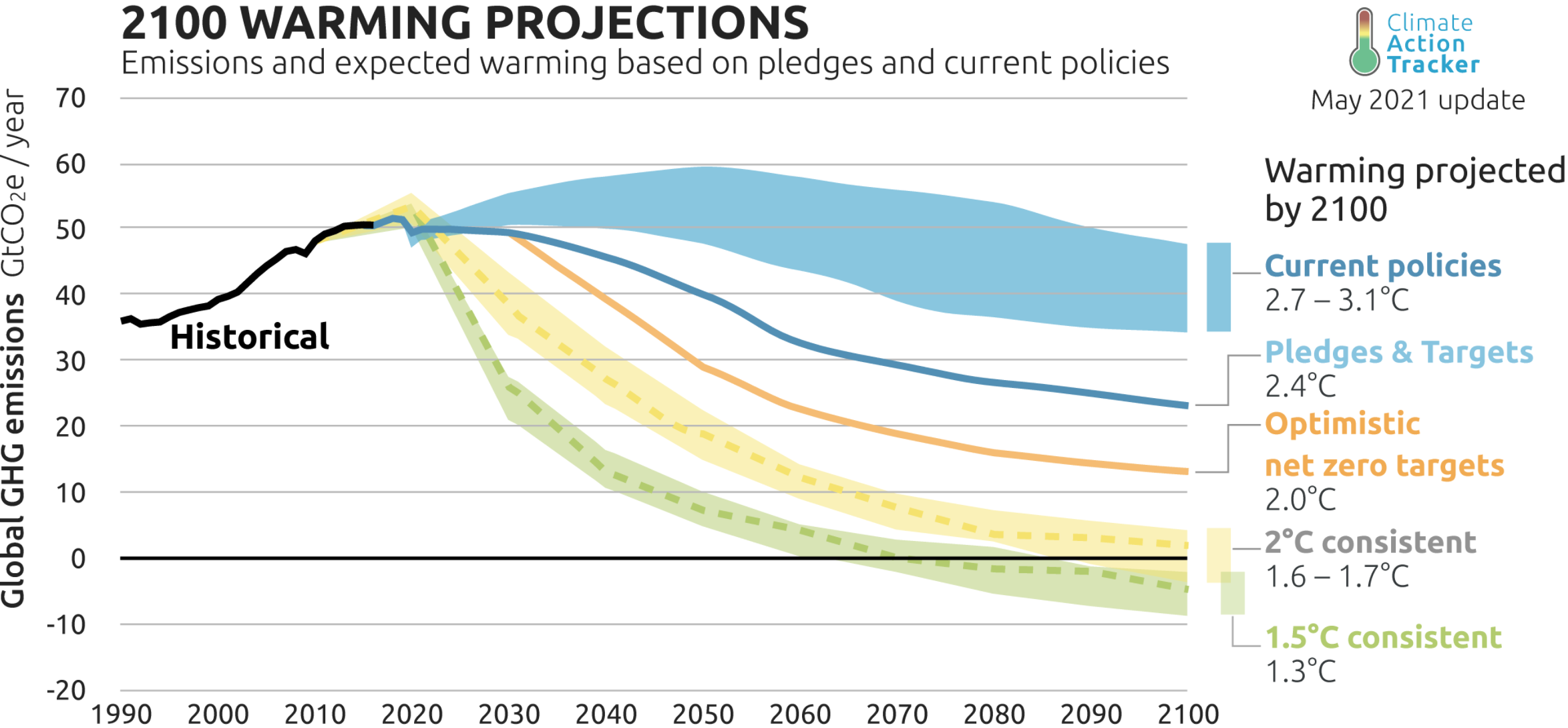

Science helps us project ourselves into the future with data-based predictions and climate models that give us a glimpse of what is to come and help inform the decisions of policymakers who are seeking to build better futures.

However, it is often hard to translate these predictions into a tangible reality made of people and their experiences. Numbers, statistics and graphs need a human face and relateable storylines that create empathy.

“Translating long term climate goals into actions means timing net-zero according to what climate models are predicting. But there is a lot of difference and uncertainty in this and we need narratives and storylines that explain these models and their predictions,” explained EIEE director Masimo Tavoni during the Science and policy: strategies, solutions and opportunities webinar.

Creating tangible storylines with strong narratives that capture the future depicted by scientific predictions and climate models is central to ensuring a better future for the next generations.

Science fiction

Science fiction as a genre strives to create imaginary futures that tell us something about the current times we live in. It helps us create fictitious futures that are somehow grounded in reality: a discovery of the future that teaches us the value of the present.

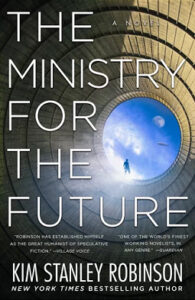

“When I was young the mars landings were the new stories and mars was a blank slate and imaginary space into which we could throw our imaginations,” explains renowned sci-fi author Kim Stanley Robinson, “But that was the 1990s. In 2021 the news that comes to us from the scientific community is that we are enacting catastrophic climate change and are currently in the era of the Anthropocene. So, this is now the story to tell.”

“When I was young the mars landings were the new stories and mars was a blank slate and imaginary space into which we could throw our imaginations,” explains renowned sci-fi author Kim Stanley Robinson, “But that was the 1990s. In 2021 the news that comes to us from the scientific community is that we are enacting catastrophic climate change and are currently in the era of the Anthropocene. So, this is now the story to tell.”

Robinson’s new book The Ministry of Information transports the reader to a not-so-distant future, around 30 years from now, where the IPCC’s current best-case scenario projections on climate change have forged the world.

The effect is a powerful depiction of the consequences of our actions on future generations. A face to face encounter with the people suffering from extreme weather events and the geopolitical tensions that will inevitably arise.

“IPCC projections are science fiction stories of what will happen if we pursue certain courses of action now. I wanted to portray a best-case scenario for about 30 years from now knowing what we now know,” explains Robinson.

The Discount Rate Hypothesis

Storytelling related to climate change raises many important issues, not least of which how much we value the future and the wellbeing of those that will live in it. If sustainable development means meeting our own needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs, as defined by the Brundtland Commission Report in 1987, then understanding and portraying the consequences of our current actions is essential and should dictate policies being implemented today.

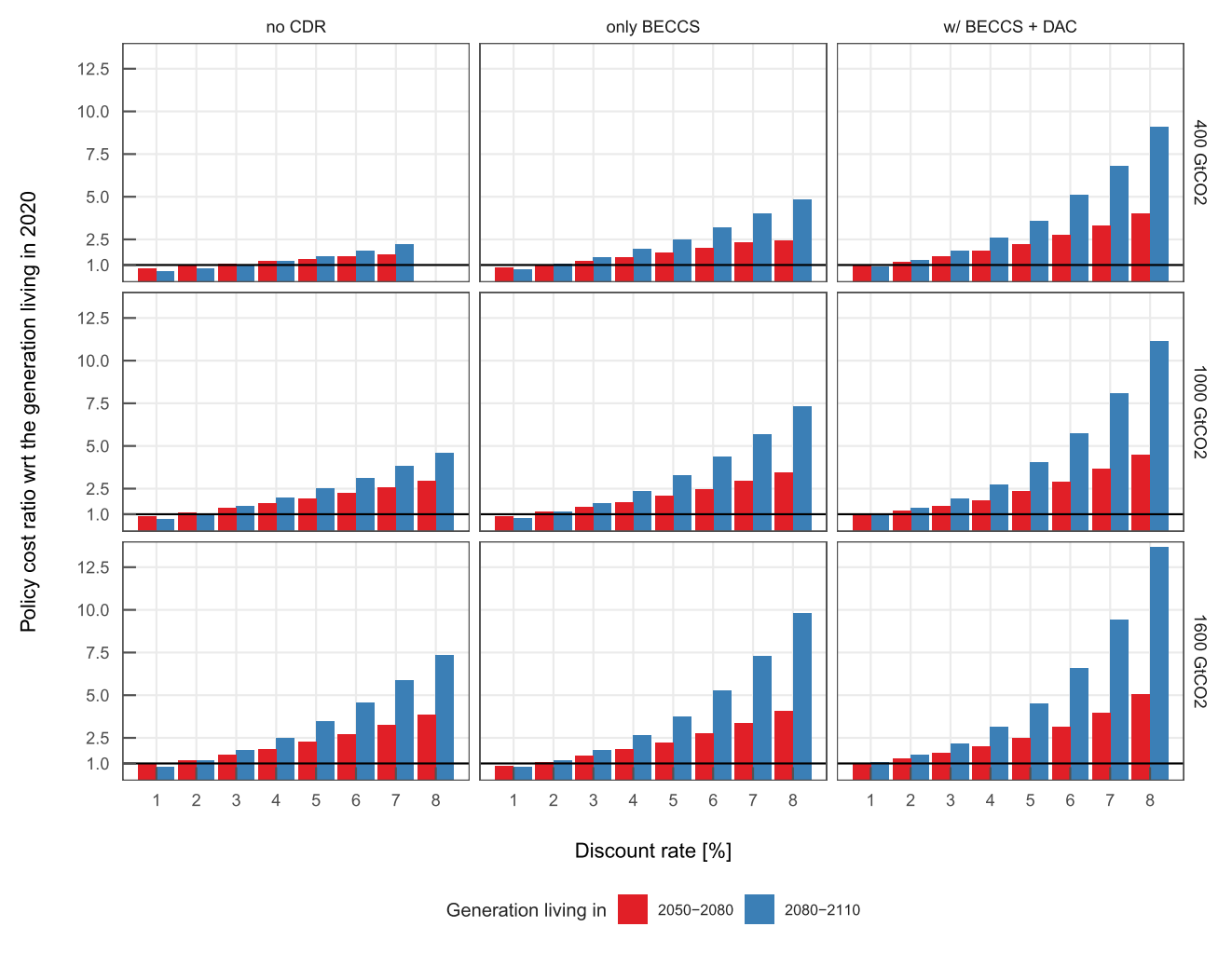

“To what extent do we value the future? This question is embedded in our evaluations. By changing the extent to which we value the future then we alter completely our understanding of who should bear the burden, and benefits, of solving the climate crisis,” explains Tavoni.

Central to these evaluations is the discount rate hypothesis. Social discount rates (SDRs) are used to give a current value on the costs and benefits that will occur in the future. With regards to climate change policymaking they help calculate how much we should invest in reigning in the effects of climate change.

This involves evaluating the cost-benefit relationship between investing in climate change mitigation and adaptation now compared to the cost-benefit of letting these fall on future generations.

“The use of a high discount rate implies that people put less weight on the future and therefore that less investment is needed now to guard against future costs. Indeed, high discount rates have been described as favouring arguments against regulations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The use of a low discount rate supports the view that we should act now to protect future generations from climate change impacts. In other words, more importance is given to future generations’ wellbeing in cost–benefit analyses,” outlines the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.

Inter-generational equity

By telling the stories of the effects of climate change on future generations we can help raise awareness about inter-generational equity. “The discount rate should be zero. We value the people of the future as much as ourselves. If you have a high discount rate, which we have now, then you are saying that the future and people of the future don’t matter to us and ethically this is indefensible,” claims Robinson.

Initiatives such as the Conference Of Youth (COY) play a strong role in advocating for intergenerational equity and ensuring that younger generations are being represented in important policy decisions taking place today but which affect their future.

“COY is designed for the youth from across the world so that we can share best practices. We ensure that young people from all across the world have a space to participate in the process. At COY16 we will produce a policy document that will then be presented at COP26,” explains Jan Kairel Guillermo, Lead, Global Affairs Unit, COY, YOUNGO.

“We need to consider environmental justice when we want to implement changes even if long term targets are often hard to work towards,” says Lodovica Cattani, Country Coordinator Italy for COY16. “It takes a lot of courage to see the climate crisis and fight the negative narrative of doom and gloom. Young people can do this, demand better policies and hold accountable their local representatives and the industry sector.”